A board the sailing yacht Rocinante, the north wind shrieks through rigging. It holds flags taut. It pushes against the boats hull, and the boat in turn pulls on her dock lines, straining. Dark clouds gallop across the sky.

Eager to begin our voyage but waiting for the norther to blow itself out, I find my mind consumed by wind. It is with me during the day, before I sleep at night, when I awake in the morning. At times, it occupies my dreams.

I do not contemplate mild breezes.

I think of the storm of 1900, with thousands dead in Texas, their bodies buried in rubble and strewn along railroad tracks and floating at sea. I think of the Great Hurricane of 1780 sweeping away more than twenty thousand souls in the Caribbean. I think of a steamship in 1857 encountering an unnamed storm off South Carolina, her crew and passengers in a bucket brigade frantically bailing while the air roared around them, before the sinking vessel took 425 people to their graves. I think of Lawrence Kern in 1930, lifted from the ground by a tornado and found, mortally injured but still alive, a mile away.

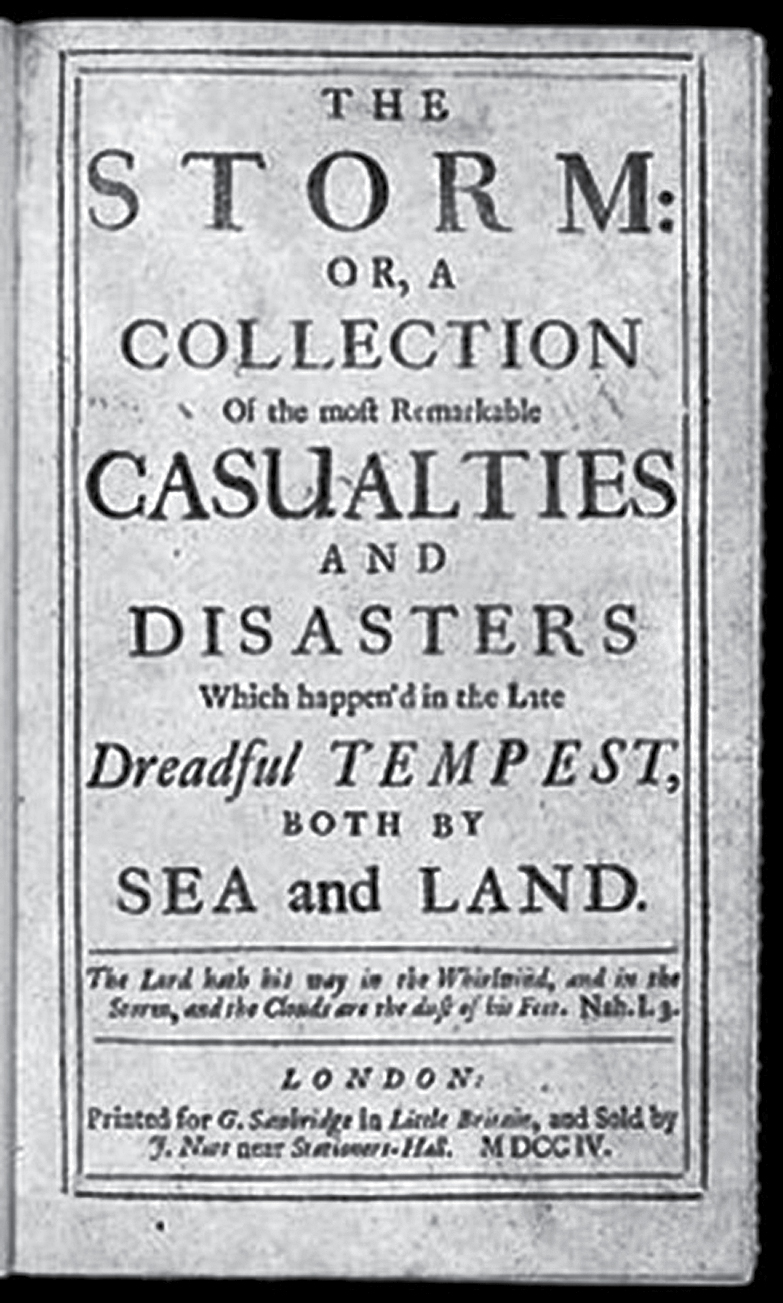

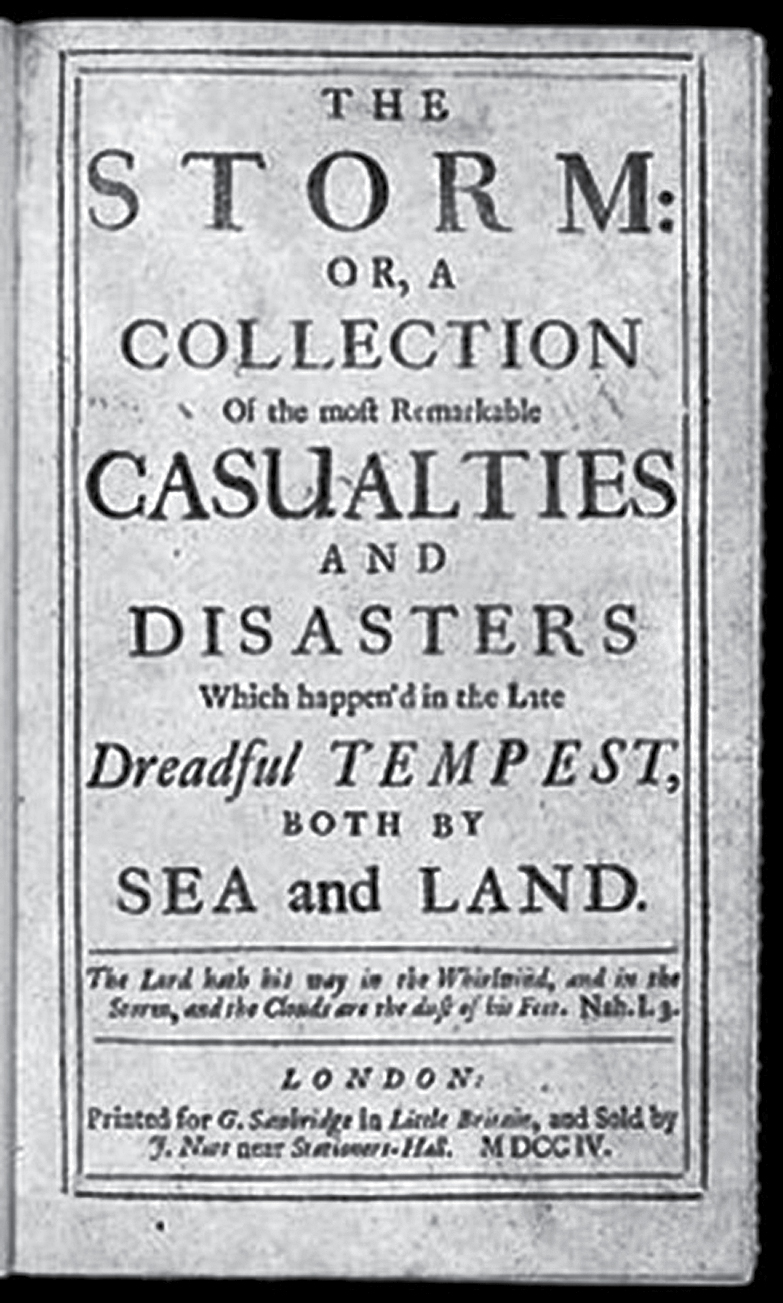

I think, too, of Daniel Defoes storm. Fifteen years before he wrote Robinson Crusoe, in a book often described as an early example of journalism, Defoe wrote The Storm: or, A Collection of the Most Remarkable Casualties and Disasters Which Happend in the Late Dreadful Tempest, Both by Sea and Land.

Daniel Defoes book, often described as an early example of journalism, did not sell well. (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

He watched the wind blow day after day for more than a week. And then he watched the wind peak. The stormthough Defoe could not have known this until later, when he collected accounts from witnessescut a path three hundred miles wide across England and Wales.

Defoe called it the greatest, the longest in duration, the widest in extent, of all the Tempests and storms that history gives any account of since. It would become known as the Great Storm of 1703. After three centuries, it is still considered to be Englands worst storm.

At first, the wind was not so strong that it could carry a man aloft. If there were no flying debris, a wind like this could be fun. One could lean into it, striking unusual poses. But there was flying debris. Wind-launched missiles killed men and women and children. Defoe himself watched blowing roof tiles hit the ground, embedding themselves, he wrote, five to eight inches into solid Earth.

As the wind grew in strength, homes shook and threatened to collapse and did collapse, but the prudent and the wise feared the outdoors more than the indoors. Most People expected the Fall of their Houses, Defoe wrote. And yet in this general Apprehension, no body durst quit their tottering Habitations; for whatever the Danger was within doors, twas worse without.

Even indoors, falling debris claimed lives. One account reported the bishop of Bath and Wells leaping from his bed as the room around him shook. He made toward the door, where he was found with his Brains dashd out.

More than one person, feeling a house tremble in the wind, reported an earthquake. But it was the wind.

Impartial, moving air shook churches just as it shook homes. Church bells, unattended, rang. Seven steeples blew down. Where steeples survived, many lost their tops or parts of their tops, sending tiles and bricks and wrought iron crashing down.

Chimneys collapsed. The wind tore rolls of lead sheathing from roofs and sent them on their way. Trees with trunks three feet and more in diameter succumbed. The storm triumphed over oaks and elms and apple trees, not in the hundreds but in the tens of thousands. They were lifted out of the ground, roots intact, and sent flying over fences and hedgerows. They were snapped off at chest height. Their trunks were twisted in ways unknown to carpenters.

Defoe reported the loss of four hundred windmills. Some tumbled, their heavy anchor posts suddenly surrendering, failing under the load. Others burned, their wooden innards ignited by the friction of moving parts rubbing one against the other as their blades spun out of control.

Seawater flew inland, carried in raging gusts. One man reported Froth and Sea moisture six or seven miles up the Country, for at that distance from the Sea, the Leaves of the Trees and Bushes, were as Salt as if they had been dipped in the Sea, which can be imputed to nothing else, but the Violent Wind. The salt water reached pastures twenty-five miles from the nearest windward coast. The Grass was so salt, the Cattel would not eat for several Days.

On land, the death toll was surprisingly light. We have reckoned, Defoe reported, 123 People killd.