Table of Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

INTRODUCTION

THE NEW AND OLD OF WHITE NATIONALISM

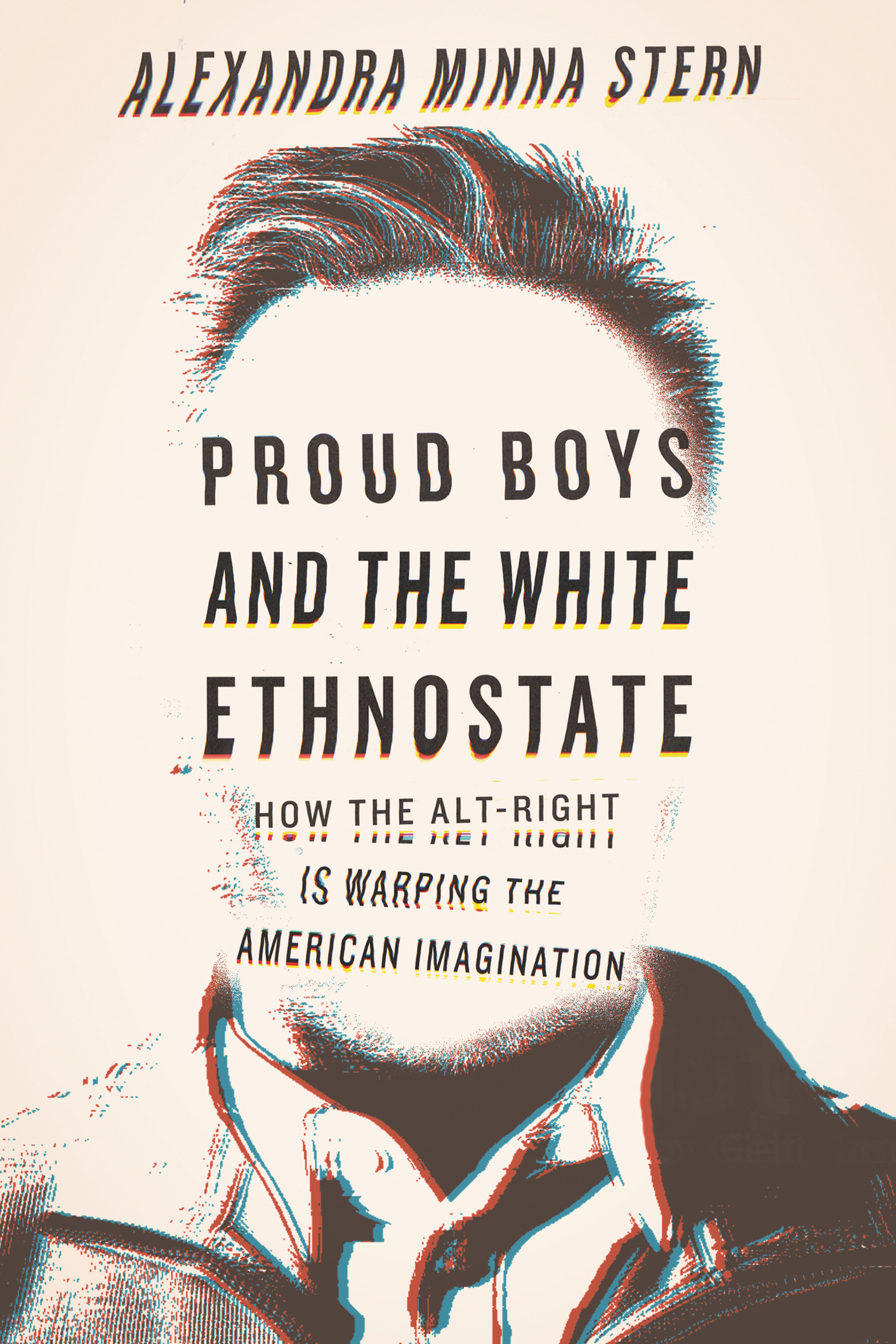

I n the summer of 2016, I was online doing some research on early twentieth-century eugenics and immigration restriction when I stumbled across the centenary edition of Madison Grants The Passing of the Great Race. It was about one month after Donald Trump had won the Republican primary, and the prospect that someone who had called Mexicans rapists, pushed birtherism, and demanded a massive border wall would become the next president of the United States seemed remote, if not impossible. As a scholar interested in the intersections of racial and reproductive politics, I was acutely aware of the history of white nationalism in America. I had studied and taught about organizations, old and new, such as the Immigration Restriction League, the Ku Klux Klan, and American Renaissance.

Now eugenics was rearing its bigoted head in a celebratory reissue of a racist classic brought out by Ostara Publications. This press was founded in 1999 to disseminate Arthur Kemps March of the Titans: The Complete History of the White Race, its flagship work, which appeared in its fourth edition in 2011. This massive text, which seems geared to homeschoolers, proposes that a civilization rises and falls by its racial homogeneity and nothing else. As long as it maintains its racial homogeneity, it will lastif it loses its racial homogeneity, and changes its racial makeup, it will fall or be replaced by a new culture. A little more online digging revealed that Ostara, with its commitment to Eurocentric history, is one of a handful of publishing ventures that produces on-demand books with titles that scream Islamophobia and white supremacy, and glorify Western civilization. According to its website, Ostara is named after the Old High German goddess of spring, Eostre, who represents the rebirth and fertility of ancient Europea trope redolent of blood and soil nationalism.

Ostara easily fit the profile of a publisher that would make The Passing of the Great Race newly available to its readers. The first edition of this tendentious book aimed to rank European races in history as groups according to physical, mental, and personality traits, and proposed three European racesTeutonics or Nordics, Alpines, and Mediterraneansanointing the first as the most advanced and comely. Beyond racist taxonomy, however, it sounded off eugenic warnings: of the degenerate immigrant masses, of impending white race suicide, and of the disharmonies of miscegenation. Alongside a plethora of early twentieth-century tracts about the biological inferiority of every racial and ethnic group save Northern Europeans, The Passing of the Great Race served as fodder for the 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act, which set racial quotas on immigrants based on nationality. This legislation hardened existing bans on Asian immigrants, placed strict limits on arrivals from Southern and Eastern Europe, and facilitated the formation of the US Border Patrol.

On the back cover of the centenary edition, Ostara praises The Passing of the Great Race as a sweeping and classic study of racial anthropology and history that stands as a call to American whites to counter the dangers both from non-white and non-north Western European immigration. Now, more than eight decades later, Spencer wants to rescue Grants later work, lamenting what he views as the unfair dismissal of the book as blunderheaded eugenic thinking associated with the Third Reich. He commends Grants entire corpus as a guiding compass for assessing racial degeneration in twenty-first-century America and a masterful model of how to deploy science to promote white nationalism.

As it turns out, the rehabilitation of American eugenicists is a pastime of the alt-right. Four years earlier, in 2012, Palingenesis Press, based in the UK, published an edition (now out of print) of The Passing of the Great Race, with a forward written by Jared Taylor, the head of American Renaissance, an organization focused on so-called race realism and an entrenched pillar of white nationalism.

Like many Americans, I was disconcerted and spooked by the alt-rights breakthrough into politics, media, and culture. Now it was surfacing in my research. I recognized its catchphrases, such as white genocide, and its recycling of stereotypes about people of color, crime rates, and IQ scores. Struck by both the familiarity and the strangeness of the alt-right, I decided to bear witness to it in real time. Was the alt-right simply old wine in new bottles, the latest incarnation of American eugenics, racism, and anti-egalitarianism? Was it something novel, with the potential to reshape politics and discourse, abetted by a sympathetic Republican presidential administration, an upsurge in national populism, and a context of simmering white rage? Could the alt-right appeal to younger generations of white Americans, who might be swayed by anxieties over demographic despair and tantalizing visions of racially homogenous homelands? What were the cultural and political implications of the circulation of the alt-right lexiconas terms such as ethnostate, human biodiversity, cuckservative, and snowflake entered the American vocabulary?

To answer these questions, I began to spend hours and hours online, taking deep dives in an ever-expanding sea of URLs, exploring sites such as Counter-Currents, Radix Journal, and that of Ostara Publications. Some of these sites had been actively posting without interruption for years, others distributing on-demand books and offering occasional posts, and some were moribund webzines with archived content. In order to mine the intellectual bedrock of the alt-right, I set out to read and analyze its quasischolarly work as a formidable form of knowledge production in an era of rising authoritarianism and ultranationalism across the globe. I began to amass my archive, concentrating on long-form essays, like Spencers article on Madison Grant, as well as monographs, anthologies, and manifestos published by alt-right publishing enterprises such as Counter-Currents, American Renaissance, and the Budapest-based Arktos. Although unlikely to ever survive academic peer review, this sizable body of literature strategically adheres to scholarly conventions, reflecting the graduate training of a good many of the alt-right mandarins.

I knew that to unearth this history of the present, I also needed to get underto excavatethe alt-right memes and tropes that had erupted online. Thus, I delved into virtual communities on Reddit, 4chan, and 8chan; visited the long-standing white nationalist message board Stormfront; read thousands of comments on YouTube and Twitter; and knocked around in the dark corners of the ugly, unmoderated virtual realms of Gab and BitChute. This unwieldy collection of sourcesmost born digitalconstitutes the archive for this book. Drawing from this unconventional archive, I have written this book in tandem with the alt-rights crescendo before and after Trumps 2016 victory, its dispersal in the wake of Charlottesville in 2017, and its subsequent attempts to reassemble and normalize. Due to the ongoing if inconsistent wave of deplatforming of some white nationalists, like Jared Taylor, and alt-light conspiracy pushers, such as Alex Jones, some of the content that I accessed online has been blocked, removed, or suspended. Scattered fragments can be plumbed from the depths of the Wayback Machine, an internet archive that has captured digital materials since 1996. This makes the screenshots I captured, and the video and audio content I transcribed, crucial and evanescent evidence of the alt-rights recent history.