Orca

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Colby, Jason M. (Jason Michael), 1974 author.

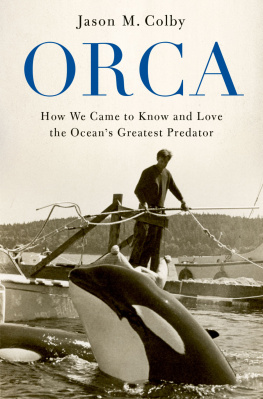

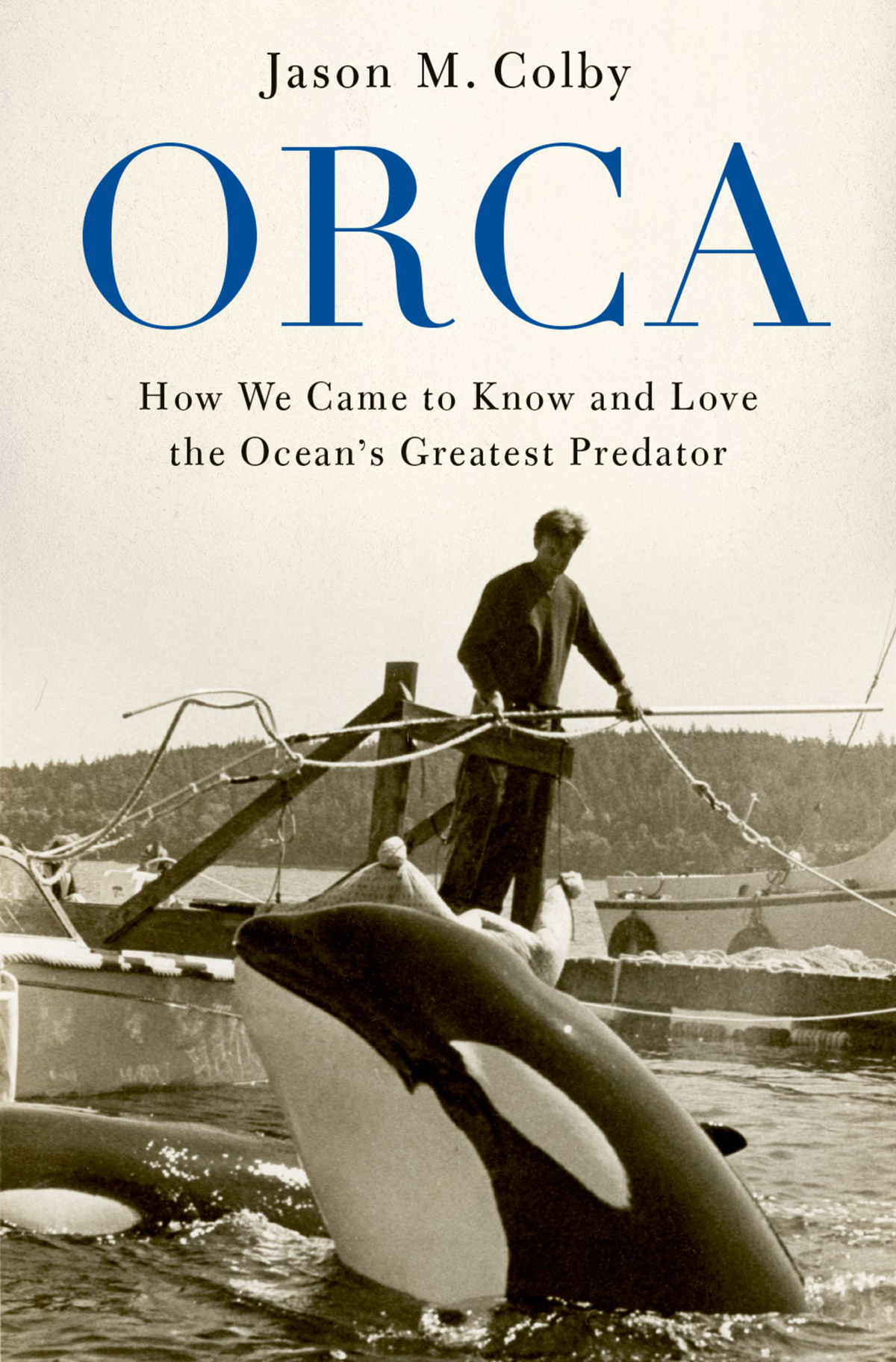

Title: Orca : how we came to know and love the oceans greatest predator / Jason M. Colby.

Description: Oxford : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017042099 (print) | LCCN 2017053474 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190673109 (Updf) | ISBN 9780190673116 (Epub) |

ISBN 9780190673093 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Killer whale. | Killer whaleConservation. |

WhalingHistory. | WhalesAnecdotes.

Classification: LCC QL737.C432 (ebook) | LCC QL737.C432 C558 2018 (print) |

DDC 599.53/6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017042099

For my father, John Colbyforever haunted by this story

We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets, 1943

Contents

Orca

On both sides of the US-Canadian border, across the Salish Sea, he helped capture killer whales for sale and displayor, as he darkly joked, for fun and profit.

Tell someone today that your father caught orcas for a living and you might as well declare him a slave trader. Killer whales are arguably the most recognized and beloved wild species on the planet. They are certainly the most profitable display animals in history, and with the 2013 release of Blackfish, their fate became an international cause clbre. Broadcast and distributed by CNN, the film became one of the most influential documentaries of all time. Already years into my research for this book when the movie came out, I found little in it surprising. But Blackfish turned my father, long conflicted about his past, sharply against orca captivity. He wasnt alone. Almost overnight, viewers, politicians, and activists turned their sights on Sea Worlda multibillion-dollar corporation famous for its killer whale shows. In this debate, it seemed there was no room for nuance or history. Millions around the world simply knew in their hearts that orcas had to be saved from captivity. What they didnt realize was that, decades earlier, captivity may have saved the worlds orcas.

Orcinus orca is the apex predator of the ocean, but that ocean has changed rapidly in recent decades. Following World War II, rising populations and new technology drove humans to plunder the sea as never before, and many regarded killer whales as dangerous pests. But then a curious thing happened. In the mid-1960s, at the height of the violence, a few daring men caught and displayed live orcas for the first time. Captive killer whales in turn captivated the public, which would never view the species, or the ocean, in the same way again.

In hindsight, the reasons for the attraction seem obvious. In addition to their panda-like coloration, orcas boast the most stunning combination of size, power, and grace on the planet. Yet it was hardly inevitable that human beings would embrace the fearsome predators. Ancient mariners depicted orcas as sea monsters, and even in modern times the species dark form and wolflike teeth seemed the stuff of nightmares. While covering Richard Byrds first expedition to Antarctica in 1928, journalist Russell Owen described the bloodthirsty killer whales as the meanest looking animals any of us have ever seen, and over the following decades other observers generally agreed. But in the span of twenty years, roughly 1962 to 1982, the ominous killer became the lovable orca.

The crucible of this transformation was the Pacific Northwest. These days, orcas are the sacred animal of this secular region. Their distinctive forms seem to appear everywhereindigenous art, tourist posters, beer labels. Shops on the Seattle waterfront stock killer whale trading cards, and local ferries sell a candy called Orca Poop. From Portland, Oregon, to Port Hardy, British Columbia, journalists breathlessly report the births and deaths of wild orcas, and networks of whale centers and museums post the lineages and comings and goings of various pods. Each year, five hundred thousand visitors from all over the world pay for whale-watching tours out of Seattle, Vancouver, Victoria, Friday Harbor, Telegraph Cove, and other portsall to catch a glimpse of the regions killer whales.

But there arent many of them. While orcas range far and wide, nearly everywhere in the ocean, only a few hundred frequent the inner waters of the Pacific Northwest, and the seventy-six animals who presently make up the regions southern resident killer whales represent less than 1 percent of the world population. Put another way, the Salish Seaa transborder ecosystem that includes the Strait of Georgia, Puget Sound, and the Strait of Juan de Fucaboasts more than one hundred thousand people for every one resident killer whale. Yet the orca is the undisputed symbol of the region.

When pressed, Northwesterners tend to attribute this status to the influence of either indigenous culture or the whale-watching industry, but the chronology doesnt fit. Local Coast Salish tribes were focused on land and fishing rights in the 1960s and 1970s and played little role in promoting

FIGURE I.1 The Salish Sea.

These figures may seem ghastly, but they pale in comparison to the toll other industries took on cetaceansthe order of mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Between 1945 and 1982 alone, the worlds whaling fleets harvested some two million great whales, while fishing vessels in the eastern Pacific knowingly killed more than six million dolphins in the process of catching yellowfin tunaa method called fishing on porpoise. During these same years, the whaling nations regularly targeted orcas, with Norway killing more than 2,000 and Japan another 1,500.

Killer whale capture had little in common with commercial whaling. The Northwesterners who chased orcas didnt plan to render their bodies into oil and meat, and on only one occasion did they hunt to kill. Rather, it was curiosity and the display industrys hunger for a signature animal that drove the pursuit. Unlike industrial whaling, however, orca catching took place in public view, in a rapidly changing region. In the past, natives and newcomers alike had harvested otters, seals, and whales, and commercial fishing boats continued to ply the Salish Sea in the 1960s and 1970s. But the extractive economy of logging and fishing that shaped the values of the old Northwest was rapidly giving way to the middle-class culture of the new. More and more people worked in offices during the week and looked to forests and local waters for weekend recreation. These urban-based residents viewed marine life as a source of pleasure rather than livelihood, and it was no coincidence that many developed misgivings about the capture of a species that local aquariums had taught them to love.