To work closely with a killer whale in a marine park requires experience, intuition, athleticism, and a lot of dramatic flair. Few people were better at it than top SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau, who, at the age of 40, was blond, vivacious, and literally the poster girl for the marine park in Orlando, Florida, appearing on billboards around the city. She decided she wanted to work with killer whales at the age of nine, during a family trip to SeaWorld, and loved animals so much that as an adult she used to throw birthday parties for her two chocolate Labs.

On February 24, 2010, Brancheau was working the Dine with Shamu show, featuring SeaWorlds largest killer whale, a 6-ton, 22-foot male known as Tili (short for Tilikum). Dine with Shamu takes place in a faux-rock-lined, 1.6-million-gallon pool that has an open-air caf wrapped around one side designed to give visitors an up-close experience with one of natures most magnificent beasts. That Wednesday, the families snacking on the lunch buffet were getting an eyeful. Brancheau bounced around on the deck of the pool, wearing a black-and-white wetsuit that echoed Tilikums coloration, as she worked him through a few of the many behaviors he had learned during his nearly 27 years as a marine-park denizen. She asked him to stick his table-sized pectoral into the air, mimic her head movements, and retrieve a fish without eating it, praising him lavishly when he followed her instructions. The audience chuckled at the sight of one of the oceans top predators performing like a circus animal.

The show ended around 1:30 P.M. As the audience started to file out, Brancheau fed Tilikum some herring (he eats up to 200 pounds a day), doused him a few times with a bucket (killer whales love all sorts of stimulation), and moved over to a shallow ledge built into the side of the pool. There, she lay down in a few inches of water, talking to him and stroking him, conducting whats known as a relationship session. Tilikum floated inert in the pool alongside her, his nose almost touching her shoulder. Brancheau was smiling, her long ponytail flaring out behind her. It was an endearing site: Man (or in this case woman) communing with whale.

One level down, a group of families gathered before the huge glass windows in the underwater viewing area. A trainer shouted up that they were ready for Tilikum. That was Brancheaus signal to instruct the orca to dive down and swim directly up to the glass. As she had done so many times before, she held up her two index fingers and drew a square in the air in front of the truck-sized creature.

Its an awesome sight when six tons of orca come gliding out of the blue, but that day, instead of waiting for his cue and behaving the way decades of daily training had conditioned him to, Tilikum did something unexpected. Jan Topoleski, a trainer who was acting as a safety spotter for Brancheau, told investigators that Tilikum took Brancheaus drifting hair into his mouth. Brancheau tried to pull it free, he said, but Tilikum yanked her into the pool. Other witnesses saw Tilikum grab Brancheau by the arm or shoulder. Either way, in an instant a cozy tableau of a trainer bonding with a marine mammal became a life-threatening emergency.

Topoleski hit the pools siren. A Signal 500 was broadcast over the SeaWorld radio net, calling for a water rescue at G pool. Staff raced to the scene. It was scary, Susanne De Wit, a Dutch tourist, told investigators. He was very wild. SeaWorld staff slapped the waters surface, signaling Tilikum to leave her. The whale ignored the command. Trainers hurried to drop a weighted net into the water to try and separate Tilikum from Brancheau or herd him through two adjoining pools and into a small medical pool that had a lifting floor. There, he could be raised out of the water and controlled.

Eyewitness accounts and the sheriffs investigative report make it clear that Brancheau fought hard. She was a strong swimmer, and a dedicated workout enthusiast who ran marathons. But she weighed just 123 pounds and was no match for a 12,000-pound killer whale. She managed to break free and swim toward the surface, but Tilikum slammed into her. She tried again. This time he grabbed her. One moment he had her by the foot, another by the back collar of her wet suit. Her water shoes came off and floated to the surface. He started pushing her with his nose like she was a toy, Paula Gillespie, one of the visitors at the underwater window, recalled. Some of the children who were watching began to cry. SeaWorld employees urgently ushered guests away. Will she be okay? one asked.

Tilikum kept dragging Brancheau through the water, shaking her violently. Finally 20 minutes after he first grabbed the trainer and now holding her by her arm - he was guided onto the medical lift. The floor was quickly raised. Even then, Tilikum refused to give her up. Trainers were forced to pry his jaws open with a stick. When they pulled Brancheau free, part of her arm came off in his mouth. His jaw had to pried open again to retrieve it. Brancheaus colleagues carried her to the pool deck and cut her wetsuit away. She had no heartbeat. The paramedics went to work with a defibrillator, but it was obvious she was gone. A sheet was pulled over her body. Tilikum had killed her.

Every safety protocol that we have failed, SeaWorld director of animal training Kelly Flaherty Clark told me a month after the incident, her voice still tight with emotion. Thats why we dont have our friend anymore, and thats why we are taking a step back.

Dawn Brancheaus death was a tragedy for her family and for SeaWorld, which had never lost a trainer before. Letters of sympathy poured in, many enclosing pictures of Brancheau and the grinning kids shed spent time with after shows. The incident was a shock to Americans accustomed to thinking of SeaWorlds killer whales, often referred to as Shamu, as a lovable national icon, with an extensive line of plush dolls and a relentlessly cheerful Twitter feed. The news media went into a frenzy, pursuing Brancheaus family, flying helicopters over Shamu Stadium, and chasing down every killer whale expert and animal rights activist with a heartbeat and an opinion. Congress piled on with a call for hearings on marine mammals at entertainment parks, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) opened an investigation. It was the most intense national killer whale mania since 1996, when Keiko, the star of the hit movie Free Willy, was rescued from a shabby marine park in Mexico City in an attempt to return him to the sea. Killer whales have never been known to fatally attack a human in the wild, and everyone wanted to know one thing: Why did Dawn Brancheau die?

To understand Brancheaus death, you need to understand Tilikums life. You need to know where he came from and what he experienced over the years leading up to the attack. You need to understand how life in a marine park is different from life in the wild. You need to tease out the patterns of behavior that have made him the most deadly whale in marine-park history. Only then can you begin to grasp how his life became the instrument of Dawn Brancheaus death.

Killer whales have been star attractions at marine parks since 1965. There are 42 alive in parks around the world today - SeaWorld owns 24 of them - and over the years more than 150 have died in captivity. Until the 1960s, no one really thought about putting a killer whale in an aquarium, much less in a show. The public knew little about them beyond the fact that they sounded dangerous. (Killer whales, or orcas, are the largest members of the dolphin family.) Fishermen tended to shoot at them with rifles if they came near salmon and herring stocks.

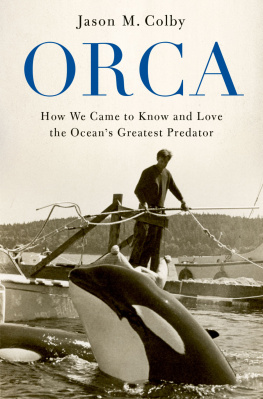

But Ted Griffin helped change all that. A young impresario who owned the Seattle Marine Aquarium, Griffin had long been obsessed with the idea of swimming with a killer whale. In June 1965, he got word of a 22-footer tangled in a fishermans nets off Namu, British Columbia. Griffin bought the 8,000-pound animal for $8,000. He towed the orca, which he named Namu, 450 miles back to Seattle in a custom-made floating pen. Namus family pod - 20 to 25 orcas - followed most of the way before giving up on him. Griffin was surprised by how gentle and intelligent Namu was. Before long, he was riding on the orcas back, and, by that September, tens of thousands of people had come to see the spectacle of the man and his killer-whale buddy. The story of their friendship was eventually chronicled in the pages of

Next page