Ethnosociology vol. I

Arktos

London 2019

Copyright 2019 by Arktos Media Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means (whether electronic or mechanical), including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Arktos.com | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Gab.ai | Minds.com | YouTube

ISBN

978-1-912975-01-3 (Softcover)

978-1-912975-00-6 (Hardback)

978-1-912975-02-0 (Ebook)

Translation

Michael Millerman

Editing

Arkacandra Jayasimha & Martin Locker

Cover and Layout

Tor Westman

Ethnosociology: Definition, Subject Matter, Methods

I. A Brief Excursus into Classical Sociology

The Basic Concepts of Sociology: The General and the Particular

Ethnosociology studies the ethnos with the help of the sociological apparatus, and for that reason we will need the basic concepts of the discipline of Sociology. We shall now make a short excursus into the fundamentals of Sociology.

Sociology is a discipline that examines society as a whole preceding its parts, as an organic , not a mechanical phenomenon; it is a discipline that emphasizes the common , or the social, and not the particular, or the individual. Psychology concerns itself with the person. Sociology, on the other hand, studies society as a whole. The fundamental principle of sociology can be summed up thus: the particular derives from the common .

Social Strata and Groups

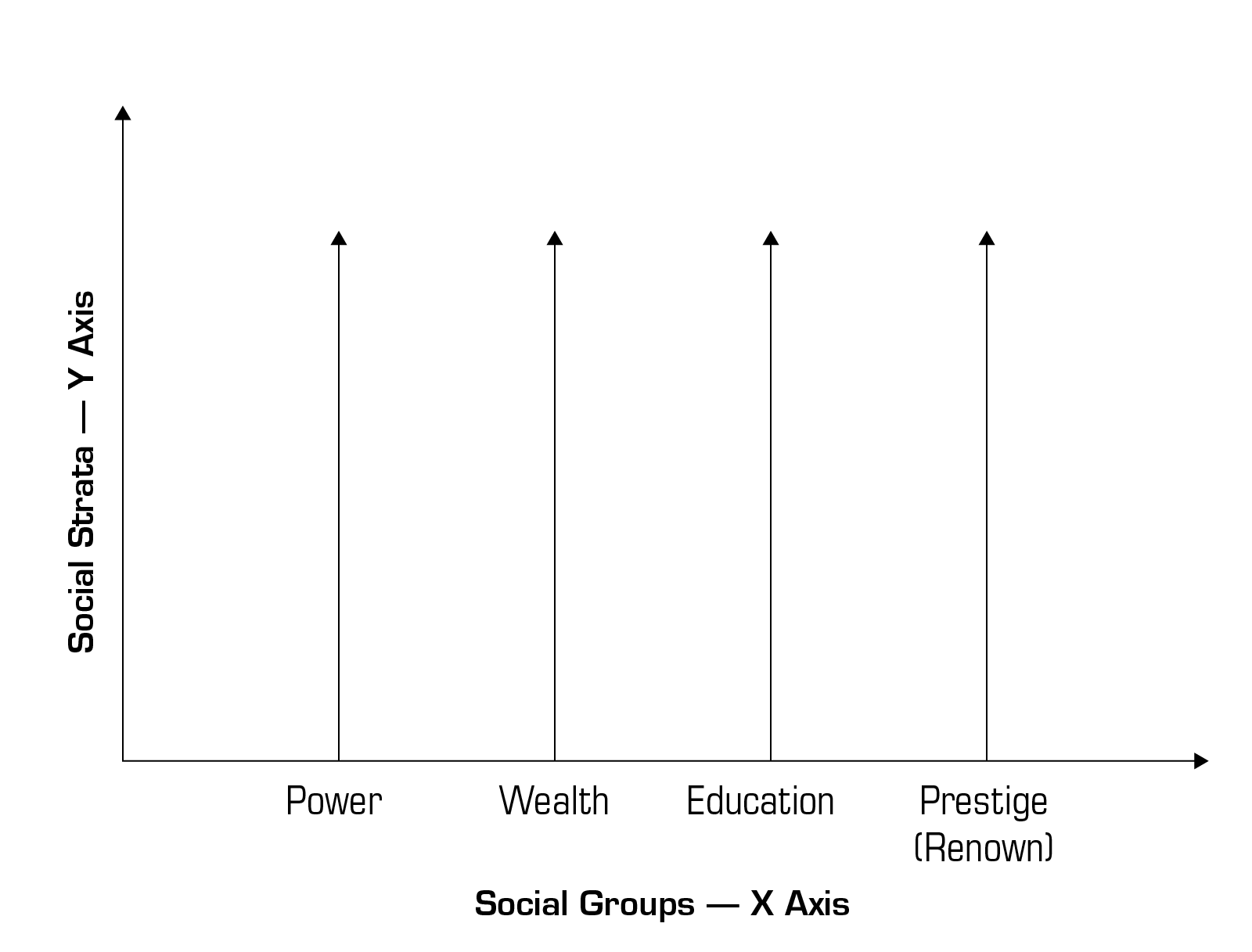

The fundamental framework of sociological knowledge is two axes, x and y , on which are arranged social strata ( x-axis ) and social groups ( y-axis ).

Figure 1. The basic model of sociology.

Of course, Sociology is a well-established scientific discipline. It has many theories, concepts, and methods for the study of society, but the fundamental meaning, scientific paradigm, and episteme of Sociology can be reduced down to this very simple diagram.

A persons position with respect to these two axes determines his status . Status consists in a set of roles.

The y -axis, on which strata or classes (understood sociologically) are arranged is called the axis of social stratification. From the sociological point of view, strata are primary in relation to other forms. On the x -axis, social groups are arranged. This is the amalgamation of people by markers of their belonging to a profession, gender, age, geographic area, ethnicity, or administrative position, drawn up in accordance with a non-hierarchical principle. Strata, for their part, imply a hierarchy.

The superimposition of these two axes provides a basic representation of the structure of a society and the place of any unit in it taken for consideration, whether collective or individual. Each social phenomenon, institution, and personality can be resolved into its components through these axes. Such resolution is sociological analysis, the main professional activity of the sociologist.

Sociology operates with the concept of inequality, the quantitative indicator of which is placed along the y -axis. The qualitative indicator is marked on the x -axis: belonging to one or another social group or to a few groups at once.

The strata define a social hierarchy, for which reason the y -axis is vertical. In themselves, groups do not yet say anything about a higher or lower position, which is why the axis on which they are arranged is horizontal. The fact that someone belongs to the group of pensioners, Orthodox Christians, or Muslims in no way makes a pensioner or a Christian higher or lower than one another. Hence groups are arranged horizontally or are at times superimposed on one another. Someone can be a pensioner or a Christian or both one and the other at the same time.

From the point of view of strata, a person can be either a rich, educated, and famous director, or a subordinate, poor, undereducated, and entirely unknown local. By a certain relativity of approach, society as a whole can be mapped onto this scale of stratification. Sociologists usually distinguish between three main classes: the upper, the middle, and the lower. Membership in each of them is evaluated according to entirely precise criteria: ones income, number of subordinates, years of education, academic level, and index of citations. A man who has thirty dollars in his pocket and sees a poor person begging might consider himself to be rich, but the sociologist will swiftly return him to reality if he asks about his monthly income. The same principle applies to renown: it might seem to someone that he is famous if he is known by two or three groups of his peers and he enjoys success among them, but a measurement of the index of citations will put him in his place if it proves that there is no mention of this person among relevant sources.

Metaphor of the Theater

From the point of view of Sociology, man is nothing other than his status or the totality of statuses, a status-set. Contained within the status is a set of roles. The totality of statuses, the carrier of which is the same individual, is a totality of role-sets. For that reason, the metaphor of the theater lies at the basis of the sociological method. In Shakespeares words: All of the worlds a stage, / And all the men and women merely players. The personal life of the actor does not exist. The actor lives in his roles. These roles can vary. The same actor can play the villain or the hero, a love-struck youth or a greedy loan shark. That which lies beneath the mask, beyond the limits of the stage, normally interests neither the theater, nor the audience, nor the producers.

It is exactly the same thing in Sociology. The sociologist studies roles and whether they are played well or not. The question By whom are they played? does not interest him. In any girl, for instance, the sociologist sees an actor and her ability to cope with the roles of beloved, wife, bride, mother, daughter, secretary, future scientist, gymnast, swimmer, cook, etc. In other words, the sociologist sees in a person a set of social statuses.

Figure 2. Status in the sociological coordinate axes.

Man as a Derivative from Society

From a sociological point of view, a person is a derivative of the two axes . The essence of the sociological person is defined depending on where on the diagram we put the dot. In Sociology, status prevails over personal qualities.

The person is derived because, being a set of statuses, he does not himself create it. He takes it over. He is inscribed into it. It is always created by something else .

In Sociology, the person is a product, a result, a detail in an enormous construction. He does not write the drama, nor is he the director. He merely plays roles, which someone else always writes. The person does not build the theater. The theater is unquestionably built: it is called society. Sociology does not set before itself the task of discovering the originator of society. This is too abstract and philosophical a question. There is an obvious fact: when we look at history, when we deal with people, we always see society. We come across it everywherein archaic, primitive, and highly-developed peoples. Furthermore, society is always built up on collective, super-individual foundations. Everywhereboth in very complex and in very primitive societiesthere exist strata and groups.

Next page