Peter Pomerantsev - 30 July

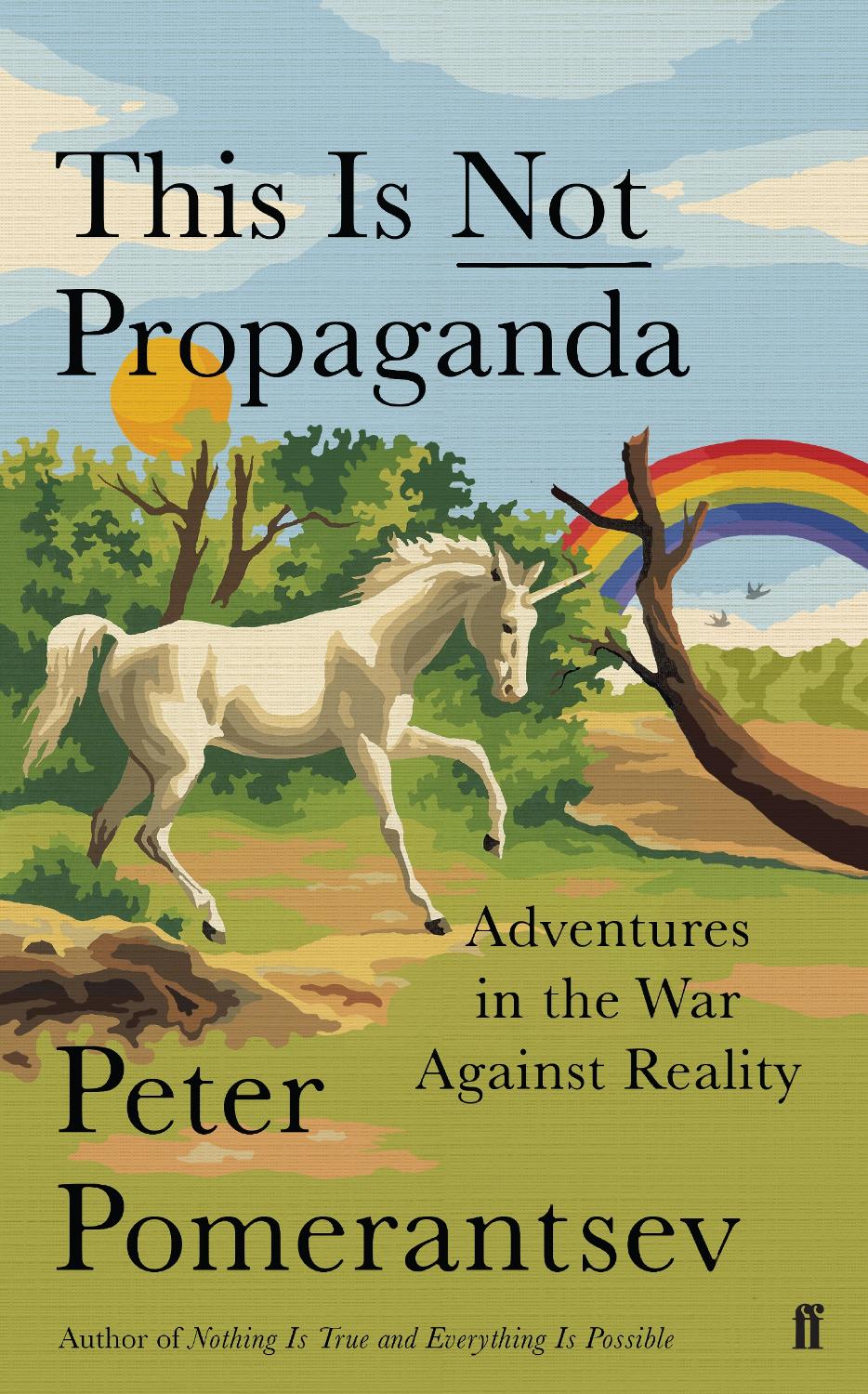

Here you can read online Peter Pomerantsev - 30 July full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 30 July 2019, publisher: Faber & Faber, genre: Science / Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:30 July

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber & Faber

- Genre:

- Year:30 July 2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

30 July: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "30 July" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

30 July — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "30 July" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This Is Not PropagandaAdventures in the War

This Is Not PropagandaAdventures in the WarAgainst RealityPeter Pomerantsev

ContentsHe came out of the sea and was arrested on the beach: two men in suits standing over his clothes as he returned from his swim. They ordered him to get dressed quickly, pull his trousers over his wet trunks. On the drive the trunks were still wet, shrinking, turning cold, leaving a damp patch on his trousers and the back seat. He had to keep them on during the interrogation. There he was, trying to keep up a dignified facade, but all the time the dank trunks made him squirm. It struck him they had done it on purpose. They were well versed in this sort of thing, these mid-ranking KGB men: masters of the small-time humiliation, the micro-mind game.Why had they arrested him here, he wondered, in Odessa, not where he lived, in Kiev? Then he realised: it was August and they wanted a few days by the seaside. In between interrogations, they would take him to the beach to go swimming themselves. One would sit with him while the other would bathe. On one of their visits to the beach an artist took out an easel and began to paint the three of them. The colonel and major grew nervous they were KGB and werent meant to have their images recorded during an operation. Go have a look at what hes drawing, they ordered their prisoner. He went over and had a look. Now it was his turn to mess with them a little: Hes not drawn a good likeness of me, but youre coming out very true to life.He had been detained for distributing copies of harmful literature to friends and acquaintances: books censored for telling the truth about the Soviet Gulag (Solzhenitsyn) or for being written by exiles (Nabokov). The case was recorded in the Chronicle of Current Events. The Chronicle was how Soviet dissidents documented suppressed facts about political arrests, interrogations, searches, trials, beatings, abuses in prison. Information was gathered via word of mouth or smuggled out of labour camps in tiny self-made polythene capsules that were swallowed and then shat out, their contents typed up and photographed in dark rooms. It was then passed from person to person, hidden in the pages of books and diplomatic pouches, until it could reach the West and be delivered to Amnesty International or broadcast on the BBC World Service, Voice of America or Radio Free Europe. It was known for its curt style:He was questioned by KGB Colonel V. P. MENSHIKOV and KGB Major V. N. MELGUNOV. He rejected all charges as baseless and unproven. He refused to give evidence about his friends and acquaintances. For all six days they were housed in the Hotel New Moscow.When one interrogator would leave, the other would pull out a book of chess puzzles and solve them, chewing on the end of a pencil. At first the prisoner wondered if this was some clever mind game, then he realised the man was just lazy, killing time at work.After six days he was permitted to go back to Kiev, but the investigation continued. On the way home from work at the library, the black car would pull up and take him for more interrogations.During that time, life went on. His fiance conceived. They married. At the back of the reception lurked a KGB photographer.He moved in with his wifes family, in a flat opposite Goloseevsky Park, where his father-in-law had put up a palace of cages for his dozens of canaries, an aviary of throbbing feathers darting against the backdrop of the park. Every time the doorbell rang he would start, scared it was the KGB, and would begin burninganything incriminating: letters, samizdat articles, lists of arrests. The canaries would beat their wings in a panic-stricken flutter. Each morning he rose at dawn, gently turned the Spidola radio to ON, pushed the dial to short-wave, wiggled and waved the antenna to dispel the fog of jamming, climbed on chairs and tables to get the best reception, steering the dial in an acoustic slalom between transmissions of East German pop and Soviet military bands, pressing his ear tight to the speaker and, through the hiss and crackle, making his way to the magical words: This is London; This is Washington. He was listening for news about arrests. He read the futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikovs 1921 essay Radio of the Future:Radio will forge the unbroken chain of the global soul and fuse mankind.The net closed around his circle. Grisha was taken to the woods and roughed up. Olga was accused of being a prostitute and, to make the point, was locked up in a VD clinic with actual prostitutes. Geli was taken to remand prison and refused treatment for so long that he went and died.Everyone prepared for the worst. His mother-in-law taught him a secret code based on sausages: If I bring sausages sliced right to left, it means weve been able to get out news of your arrest to the West, and its been broadcast on the radio. If I slice them left to right, it means we failed.It sounds like something out of an old joke or a bad film, but its nevertheless true, he would write later. When the KGB come at dawn, and you mumble drowsily, Whos there? they often shout, Telegram! You proceed in semi-sleep, trying not to wake up toomuch so you can still go back to a snug dream. One moment, you moan, pull on the nearest trousers, dig out some change to pay the messenger, open the door. And the most painful part is not that they have come for you, or that they got you up so early, but that you, like some small boy, fell for the lie about delivering a telegram. You squeeze in your hot palm the suddenly sweaty change, holding back tears of humiliation.At 08.00 a.m. on 30 September 1977, in between interrogations, their child was born. My grandmother wanted me to be called Pinhas, after her grandfather. My parents wanted Theodore. I ended up being named Piotr, the first of several renegotiations of my name.*Forty years have passed since my parents were pursued by the KGB for pursuing the simple right to read, to write, to listen to what they chose and to say what they wanted. Today, the world they hoped for, in which censorship would fall like the Berlin Wall, can seem much closer: we live in what academics call an era of information abundance. But the assumptions that underlay the struggles for rights and freedoms in the twentieth century between citizens armed with truth and information and regimes with their censors and secret police have been turned upside down. We now have more information than ever before, but it hasnt brought only the benefits we expected.More information was supposed to mean more freedom to stand up to the powerful, but its also given them new ways to crush and silence dissent. More information was supposed to mean a more informed debate, but we seem less capable of deliberation than ever. More information was supposed to mean mutual understanding across borders, but it has also made possible new and more subtle forms of conflict and subversion. We live in a world of mass persuasion run amok, where the means of manipulation have gone forth and multiplied, a world of dark ads, psy-ops, hacks, bots, soft facts, deep fakes, fake news, ISIS, Putin, trolls, TrumpForty years after my fathers detention and interrogation, I find myself following the palest of imprints of my parents journey, though with none of their courage, risk or certainty. As I write this and given the economic turbulence, this might not be the case when you read it I run a programme in an institute at a London university that researches the newer breeds of influence campaigns, what might casually be referred to as propaganda, a term so fraught and fractured in its interpretation defined by some as deception and by others as the neutral activity of propagation that I avoid using it.I should add that Im not an academic, nor is this an academic work. Im a lapsed television producer, and though I continue to write articles and sometimes present radio programmes, I now often find myself looking at my old media world askance, at times appalled by what weve wrought. In my research I meet Twitter revolutionaries and pop-up populists, trolls and elves, behavioural change visionaries and info-war charlatans, jihadi fanboys, Identitarians, meta-politicians, truth cops and bot herders. Then I bring everything that Ive learnt back to the hexagonal, concrete tower where my office has its temporary home and shape it into sensible Conclusions and Recommendations for neatly formatted reports and PowerPoint presentations, which diagnose and propose ways of remedying the flood of disinformation, fake news, information war and the war on information.Remedying what, however? The neat little bullet points of my reports assume that there really is a coherent system that can be amended, that a few technical recommendations applied to new information technologies can fix everything. Yet the problems go far deeper. When, as part of my daily work, I present my findings to the representatives of the waning Liberal Democratic Order, the one formed in no little part out of the conflicts of the Cold War, I am struck by how lost they seem. Politicians no longer know what their parties represent; bureaucrats no longer know where power is located; billionaire foundations advocate for an open society they can no longer quite define. Big words that once seemed swollen with meaning, words that previous generations were ready to sacrifice themselves for democracy and freedom, Europe and the West have been so thoroughly left behind by life that they seem like empty husks in my hands, the last warmth and light draining out of them, or like computer files to which we have forgotten the password and cant access any more.The very language we use to describe ourselves left and right, liberal and conservative has been rendered near meaningless. And its not just conflicts or elections that are affected. I can see people I have known my whole life slipping away from me on social media, reposting conspiracies from sources I have never heard of; Internet undercurrents pulling whole families apart, as if we never really knew each other, as if the algorithms know more about us than we do, as if we are becoming subsets of our own data, as if that data is rearranging our relations and identities with its own logic or perhaps in order to serve the interests of someone we cant even see. The grand vessels of old media the cathode-ray tubes of radios and televisions, the spines of books and the printing presses of newspapers that contained and controlled identity and meaning, who we were and how we talked to one another, how we explained the world to our children, how we spoke to our past, how we defined news and opinion, satire and seriousness, right and wrong, true, false, real, unreal these vessels have cracked and burst, breaking up the old patterns of how what relates to whom, who speaks to whom and how, magnifying, shrinking, distorting all proportions, sending us spinning in disorientating spirals where words lose shared meanings. I hear the same phrases in Odessa, Manila, Mexico City, New Jersey: There is so much information, misinformation, so much of everything that I dont know whats true any more. Often I hear the phrase I feel the world is moving beneath my feet. I catch myself thinking, I feel that everything that I thought solid is now unsteady, liquid.This book explores the wreckage, searches what sparks of sense can be salvaged from it, rising from the dank corners of the Internet where trolls torture their victims, passing through the tussles over the stories that make sense of our societies, and ultimately trying to understand how we define ourselves.Part 1 will take us from the Philippines to the Gulf of Finland, where we will learn how to break people with new information instruments, in ways more subtle than the old ones used by the KGB.Part 2 will move from the western Balkans to Latin America and the European Union, where we will learn new ways to break whole resistance movements and their mythology.Part 3 explores how one country can destroy another almost without touching it, blurring the contrast between war and peace, domestic and international and where the most dangerous element may be the idea of information war itself.Part 4 will explore how the demand for a factual politics is reliant on a certain idea of progress and the future, and how the collapse of that idea of the future has made mass murder and abuse even more possible.In Part 5 I will argue that in this flux, politics becomes a struggle to control the construction of identity. Everyone from religious extremists to pop-up populists wants to create new versions of the people even in Britain, a country where identity always seemed so fixed.In Part 6 I will look for the future in China and in Chernivtsi.Throughout the book I will travel, some of the time through space, but not always. The physical and political maps delineating continents, countries and oceans, the maps I grew up with, can be less important than the new maps of information flows. These network maps are generated by data scientists. They call the process surfacing. One takes a keyword, a message, a narrative and casts it into the ever-expanding pool of the worlds data. The data scientist then surfaces the people, media outlets, social media accounts, bots, trolls and cyborgs pushing or interacting with those keywords, narratives and messages.These network maps, which look like fields of pin mould or photographs of distant galaxies, show how outdated our geographic definitions are, revealing unexpected constellations where anyone from anywhere can influence everyone everywhere. Russian hackers run ads for Dubai hookers alongside anime memes supporting far-right parties in Germany. A rooted cosmopolitan sitting at home in Scotland guides activists away from police during riots in Istanbul. ISIS publicity lurks behind links to iPhonesRussia, with its social media squadrons, haunts these maps. Not because it is the force that can still move earth and heaven as it could in the Cold War, but because the Kremlins rulers are particularly adept at gaming elements of this new age, or at the very least are good at getting everyone to talk about how good they are, which could be the most important trick of all. As I will explain, this is not entirely accidental: precisely because they had lost the Cold War, Russian spin doctors and media manipulators managed to adapt to the new world quicker than anyone in the thing once known as the West. Between 2001 and 2010 I lived in Moscow and saw close up the same tactics of control and the same pathologies in public opinion which have since sprouted everywhere.But as this book travels through information flows and across networks and countries it also looks back in time, to the story of my parents, to the Cold War. This is not a family memoir as such; rather, I am concerned with where my familys story intersects with my subject. This is in part to see how the ideals of the past have fallen apart in the present and what, if anything, can still be gleaned from them. When all is swirling I find myself instinctively looking back, searching for a connection with the past in order to find a way to think about the future.But as I researched and wrote these sections of family history I was struck by something else: the extent to which our private thoughts, creative impulses and senses of self are shaped by information forces greater than ourselves. If there is one thing Ive been impressed with while browsing the shelves in the spiral-shaped library of my university, it is that one has to look beyond just news and politics and also consider poetry, schools, the language of bureaucracy and leisure to understand, as French philosopher Jacques Ellul put it, the formation of mens attitudes. This process is sometimes more evident in my family, because the dramas and ruptures of our lives makes it easier to see where those information forces, like vast weather systems, begin and end.Freedom of speech versus censorship was one of the clearer confrontations of the twentieth century. After the Cold War, freedom of speech appeared to have emerged victorious in many places. But what if the powerful can use information abundance to find new ways of stifling you, flipping the ideals of freedom of speech to crush dissent, while always leaving enough anonymity to be able to claim deniability?The Disinformation ArchitectureConsider the Philippines. In 1977, as my parents were experiencing the pleasures of the KGB, the Philippines was ruled by Colonel Ferdinand Marcos, a US-backed military dictator, under whose regime, a quick search of the Amnesty International website informs me, 3,257 political prisoners were killed, 35,000 tortured and 70,000 incarcerated. Marcos had a very theatrical philosophy of the role torture could play in pacifying society. Instead of being merely disappeared, 77 per cent of those killed were displayed by the side of roads as warnings to others. Victims might have their brains removed, for example, and their empty skulls stuffed with their underpants. Or they could be cut into pieces, so one would pass body parts on the way to market. Marcoss regime fell in 1986 in the face of mass protests, the US relinquishing its support and parts of the army defecting. Millions came out on the streets. It was meant to be a new day: an end to corruption, an end to the abuse of human rights. Marcos was exiled and lived out his last years in Hawaii.Today Manila greets you with sudden gusts of rotting fish and popcorn smells, wafts of sewage and cooking oil, which leave you retching on the pavement. Actually, pavement is the wrong word. There are few, in the sense of broad walkways where you can stroll. Instead, there are thin ledges that run along the rims of malls and skyscrapers, where you inch along beside the lava of traffic. Between the malls the city drops into deep troughs of slums, where at night the homeless sleep encased in silver foil, their feet sticking out, flopped over in alleys between bars boasting midget boxing and karaoke parlours where you can hire troupes of girls, in dresses so tight they cling to their thighs like pincers, to sing Korean pop songs with you.During the day you negotiate the spaces between mall, slum and skyscraper along elevated networks of crowded narrow walkways that are suspended in mid-air, winding in between the multistorey motorways. You duck your head to miss the buttresses of flyovers, flinch from the barrage of honks and sirens below, suddenly finding yourself at eye level with a pumping train or eye to eye with the picture of a woman eating Spam on one of the colossal advertising billboards. The billboards are everywhere, separating slum from skyscraper. Between 1898 and 1946 the Philippines was under US administration (apart from the Japanese occupation between 1942 and 1945). US navy bases have been present ever since, and US military food has become a delicacy. On one poster a happy housewife feeds her handsome husband tuna chunks from a tin. Elsewhere a picture of a dripping, roasting ham sits over a steaming river in which street kids swim; behind them an electric sign flashes Jesus Will Save You. This is a Catholic country: three hundred years of Spanish colonialism preceded Americas fifty (We had three hundred years of the Church and fifty years of Hollywood, Filipinos joke). The malls have churches you can worship in and guards to keep out the poor. Its a city of twenty-two million with almost no notion of common public space. Inside, the malls are perfumed with overpowering air freshener: lavender in the cheaper ones with their fields of fast-food outlets; a lighter lemon scent in the more sophisticated. This makes them smell like toilets, so the odour of the latrine never leaves you, whether its sewage outside or the malls inside.Soon you start noticing the selfies. Everyone is at it: the sweaty guy in greasy flip-flops riding the metal canister of a public bus; the Chinese girls waiting for their cocktails in the malls. The Philippines has the worlds highest use of selfies; the highest use of social media per capita; the highest use of text messages. Some put this down to the importance of family and personal connections as a means of getting by in the face of ineffective government. Nor are the selfies narcissistic necessarily: you trust people whose faces you can see.And with the rise of social media the Philippines has become a capital for a new breed of digital-era manipulation.I meet with P in one of the oases of malls next to sky-blue-windowed skyscrapers. He insists I cant use his name, but you can tell hes torn, desperate for recognition for the campaigns he cant take credit for. Hes in his early twenties, dressed as if he were a member of a Korean boy band, and whether hes talking about getting a president elected or his Instagram account registered with a blue tick (which denotes status), theres almost no change in his always heightened emotions.Theres a happiness to me if Im able to control the people. Maybe its a bad thing. It satisfies my ego, something deeper in me Its like becoming a god in the digital side, he exclaims. But it doesnt sound creepy, more like someone playing the role of the baddie in a musical farce.He began his online career at the age of fifteen, creating an anonymous page that encouraged people to speak about their romantic experiences. Tell me about your worst break-up, he would ask. What was your hottest date? He shows me one of his Facebook groups: it has more than three million members.While still at school he created new groups, each one with a different profile: one dedicated to joy, for example, another to mental strength. He was only sixteen when he began to be approached by corporations who would ask him to sneak in some mentions of their products. He honed his technique. For a week he would get a community to talk about love, for example, who they cared about the most. Then he would move the conversation to fear for your loved ones, the fear of losing someone. Then he would slide in a product: take this medicine and it will help extend the lives of loved ones.He claims that by the age of twenty he had fifteen million followers across all the platforms. The modest middle-class boy from the provinces could suddenly afford his own condo in a Manila skyscraper.After advertising, his next challenge was politics. At that point, political PR was all about getting journalists to write what you wanted. What if you could shape the whole conversation through social media?He pitched his approach to several parties, but the only candidate who would take P on was Rodrigo Duterte, an outsider who looked to social media as a new route to victory. One of Dutertes main selling points as a candidate was busting drug crime. He even boasted of driving around on a motorcycle and shooting drug dealers while he was mayor of Davao City, down in the deep south of the country. At the time, P was already in college, attending lectures on the Little Albert experiment from the 1920s, in which a toddler was exposed to frightening sounds whenever he saw a white rat, leading to him being afraid of all furry animals. P says this inspired him to try something similar with Duterte.First, he created a series of Facebook groups in different cities. They were innocuous enough, just discussion boards of what was on in town. The trick was to put them in the local dialect, of which there are hundreds in the Philippines. After six months, each group had in the region of 100,000 members. Then his administrators would start posting one local crime story per day, every day, to coincide with peak Internet traffic. The crime stories were real enough, but then Ps people would write comments that connected the crime to drugs: They say the killer was a drug dealer, or This one was a victim of a pusher. After a month they dropped in two stories per day; a month later, three per day.Drug crime became a hot topic, and Duterte drew ahead in the polls. P says this is when he fell out with the other PR people in the team and quit to join another candidate. This one was running on economic competence rather than fear. P claims he managed to get his rating up by more than five points, but it was too late to turn the tide and Duterte was elected president. Now he sees any number of PR people taking the credit for Duterte, and it riles him.The trouble with interviewing anyone who works in this world is that they always tend to amplify their impact. It comes with the profession. Did P create Duterte? Of course not. There would have been many factors that drove the conversation about drug crime, not least Dutertes own pronouncements. Nor was busting drug crime Dutertes only selling point: I have talked to supporters of his who were attracted by the image of a provincial fighting the elites of Imperial Manila and the prim Catholic Church establishment. But Ps account of digital influence does echo some academic studies.In Architects of Networked Disinformation, Dr Jonathan Corpus Ong of the University of Massachusetts and Dr Jason Cabaes of Leeds University spent twelve months interviewing the protagonists of what Ong called Manilas disinformation architecture, which was made use of by every party in the country. At the top were what he described as the chief architects of the system. They came from advertising and PR firms, lived in sleek apartments in the skyscrapers and described their work in an almost mythical way, comparing themselves to characters from the hit HBO fantasy TV seriesNext page

ContentsHe came out of the sea and was arrested on the beach: two men in suits standing over his clothes as he returned from his swim. They ordered him to get dressed quickly, pull his trousers over his wet trunks. On the drive the trunks were still wet, shrinking, turning cold, leaving a damp patch on his trousers and the back seat. He had to keep them on during the interrogation. There he was, trying to keep up a dignified facade, but all the time the dank trunks made him squirm. It struck him they had done it on purpose. They were well versed in this sort of thing, these mid-ranking KGB men: masters of the small-time humiliation, the micro-mind game.Why had they arrested him here, he wondered, in Odessa, not where he lived, in Kiev? Then he realised: it was August and they wanted a few days by the seaside. In between interrogations, they would take him to the beach to go swimming themselves. One would sit with him while the other would bathe. On one of their visits to the beach an artist took out an easel and began to paint the three of them. The colonel and major grew nervous they were KGB and werent meant to have their images recorded during an operation. Go have a look at what hes drawing, they ordered their prisoner. He went over and had a look. Now it was his turn to mess with them a little: Hes not drawn a good likeness of me, but youre coming out very true to life.He had been detained for distributing copies of harmful literature to friends and acquaintances: books censored for telling the truth about the Soviet Gulag (Solzhenitsyn) or for being written by exiles (Nabokov). The case was recorded in the Chronicle of Current Events. The Chronicle was how Soviet dissidents documented suppressed facts about political arrests, interrogations, searches, trials, beatings, abuses in prison. Information was gathered via word of mouth or smuggled out of labour camps in tiny self-made polythene capsules that were swallowed and then shat out, their contents typed up and photographed in dark rooms. It was then passed from person to person, hidden in the pages of books and diplomatic pouches, until it could reach the West and be delivered to Amnesty International or broadcast on the BBC World Service, Voice of America or Radio Free Europe. It was known for its curt style:He was questioned by KGB Colonel V. P. MENSHIKOV and KGB Major V. N. MELGUNOV. He rejected all charges as baseless and unproven. He refused to give evidence about his friends and acquaintances. For all six days they were housed in the Hotel New Moscow.When one interrogator would leave, the other would pull out a book of chess puzzles and solve them, chewing on the end of a pencil. At first the prisoner wondered if this was some clever mind game, then he realised the man was just lazy, killing time at work.After six days he was permitted to go back to Kiev, but the investigation continued. On the way home from work at the library, the black car would pull up and take him for more interrogations.During that time, life went on. His fiance conceived. They married. At the back of the reception lurked a KGB photographer.He moved in with his wifes family, in a flat opposite Goloseevsky Park, where his father-in-law had put up a palace of cages for his dozens of canaries, an aviary of throbbing feathers darting against the backdrop of the park. Every time the doorbell rang he would start, scared it was the KGB, and would begin burninganything incriminating: letters, samizdat articles, lists of arrests. The canaries would beat their wings in a panic-stricken flutter. Each morning he rose at dawn, gently turned the Spidola radio to ON, pushed the dial to short-wave, wiggled and waved the antenna to dispel the fog of jamming, climbed on chairs and tables to get the best reception, steering the dial in an acoustic slalom between transmissions of East German pop and Soviet military bands, pressing his ear tight to the speaker and, through the hiss and crackle, making his way to the magical words: This is London; This is Washington. He was listening for news about arrests. He read the futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikovs 1921 essay Radio of the Future:Radio will forge the unbroken chain of the global soul and fuse mankind.The net closed around his circle. Grisha was taken to the woods and roughed up. Olga was accused of being a prostitute and, to make the point, was locked up in a VD clinic with actual prostitutes. Geli was taken to remand prison and refused treatment for so long that he went and died.Everyone prepared for the worst. His mother-in-law taught him a secret code based on sausages: If I bring sausages sliced right to left, it means weve been able to get out news of your arrest to the West, and its been broadcast on the radio. If I slice them left to right, it means we failed.It sounds like something out of an old joke or a bad film, but its nevertheless true, he would write later. When the KGB come at dawn, and you mumble drowsily, Whos there? they often shout, Telegram! You proceed in semi-sleep, trying not to wake up toomuch so you can still go back to a snug dream. One moment, you moan, pull on the nearest trousers, dig out some change to pay the messenger, open the door. And the most painful part is not that they have come for you, or that they got you up so early, but that you, like some small boy, fell for the lie about delivering a telegram. You squeeze in your hot palm the suddenly sweaty change, holding back tears of humiliation.At 08.00 a.m. on 30 September 1977, in between interrogations, their child was born. My grandmother wanted me to be called Pinhas, after her grandfather. My parents wanted Theodore. I ended up being named Piotr, the first of several renegotiations of my name.*Forty years have passed since my parents were pursued by the KGB for pursuing the simple right to read, to write, to listen to what they chose and to say what they wanted. Today, the world they hoped for, in which censorship would fall like the Berlin Wall, can seem much closer: we live in what academics call an era of information abundance. But the assumptions that underlay the struggles for rights and freedoms in the twentieth century between citizens armed with truth and information and regimes with their censors and secret police have been turned upside down. We now have more information than ever before, but it hasnt brought only the benefits we expected.More information was supposed to mean more freedom to stand up to the powerful, but its also given them new ways to crush and silence dissent. More information was supposed to mean a more informed debate, but we seem less capable of deliberation than ever. More information was supposed to mean mutual understanding across borders, but it has also made possible new and more subtle forms of conflict and subversion. We live in a world of mass persuasion run amok, where the means of manipulation have gone forth and multiplied, a world of dark ads, psy-ops, hacks, bots, soft facts, deep fakes, fake news, ISIS, Putin, trolls, TrumpForty years after my fathers detention and interrogation, I find myself following the palest of imprints of my parents journey, though with none of their courage, risk or certainty. As I write this and given the economic turbulence, this might not be the case when you read it I run a programme in an institute at a London university that researches the newer breeds of influence campaigns, what might casually be referred to as propaganda, a term so fraught and fractured in its interpretation defined by some as deception and by others as the neutral activity of propagation that I avoid using it.I should add that Im not an academic, nor is this an academic work. Im a lapsed television producer, and though I continue to write articles and sometimes present radio programmes, I now often find myself looking at my old media world askance, at times appalled by what weve wrought. In my research I meet Twitter revolutionaries and pop-up populists, trolls and elves, behavioural change visionaries and info-war charlatans, jihadi fanboys, Identitarians, meta-politicians, truth cops and bot herders. Then I bring everything that Ive learnt back to the hexagonal, concrete tower where my office has its temporary home and shape it into sensible Conclusions and Recommendations for neatly formatted reports and PowerPoint presentations, which diagnose and propose ways of remedying the flood of disinformation, fake news, information war and the war on information.Remedying what, however? The neat little bullet points of my reports assume that there really is a coherent system that can be amended, that a few technical recommendations applied to new information technologies can fix everything. Yet the problems go far deeper. When, as part of my daily work, I present my findings to the representatives of the waning Liberal Democratic Order, the one formed in no little part out of the conflicts of the Cold War, I am struck by how lost they seem. Politicians no longer know what their parties represent; bureaucrats no longer know where power is located; billionaire foundations advocate for an open society they can no longer quite define. Big words that once seemed swollen with meaning, words that previous generations were ready to sacrifice themselves for democracy and freedom, Europe and the West have been so thoroughly left behind by life that they seem like empty husks in my hands, the last warmth and light draining out of them, or like computer files to which we have forgotten the password and cant access any more.The very language we use to describe ourselves left and right, liberal and conservative has been rendered near meaningless. And its not just conflicts or elections that are affected. I can see people I have known my whole life slipping away from me on social media, reposting conspiracies from sources I have never heard of; Internet undercurrents pulling whole families apart, as if we never really knew each other, as if the algorithms know more about us than we do, as if we are becoming subsets of our own data, as if that data is rearranging our relations and identities with its own logic or perhaps in order to serve the interests of someone we cant even see. The grand vessels of old media the cathode-ray tubes of radios and televisions, the spines of books and the printing presses of newspapers that contained and controlled identity and meaning, who we were and how we talked to one another, how we explained the world to our children, how we spoke to our past, how we defined news and opinion, satire and seriousness, right and wrong, true, false, real, unreal these vessels have cracked and burst, breaking up the old patterns of how what relates to whom, who speaks to whom and how, magnifying, shrinking, distorting all proportions, sending us spinning in disorientating spirals where words lose shared meanings. I hear the same phrases in Odessa, Manila, Mexico City, New Jersey: There is so much information, misinformation, so much of everything that I dont know whats true any more. Often I hear the phrase I feel the world is moving beneath my feet. I catch myself thinking, I feel that everything that I thought solid is now unsteady, liquid.This book explores the wreckage, searches what sparks of sense can be salvaged from it, rising from the dank corners of the Internet where trolls torture their victims, passing through the tussles over the stories that make sense of our societies, and ultimately trying to understand how we define ourselves.Part 1 will take us from the Philippines to the Gulf of Finland, where we will learn how to break people with new information instruments, in ways more subtle than the old ones used by the KGB.Part 2 will move from the western Balkans to Latin America and the European Union, where we will learn new ways to break whole resistance movements and their mythology.Part 3 explores how one country can destroy another almost without touching it, blurring the contrast between war and peace, domestic and international and where the most dangerous element may be the idea of information war itself.Part 4 will explore how the demand for a factual politics is reliant on a certain idea of progress and the future, and how the collapse of that idea of the future has made mass murder and abuse even more possible.In Part 5 I will argue that in this flux, politics becomes a struggle to control the construction of identity. Everyone from religious extremists to pop-up populists wants to create new versions of the people even in Britain, a country where identity always seemed so fixed.In Part 6 I will look for the future in China and in Chernivtsi.Throughout the book I will travel, some of the time through space, but not always. The physical and political maps delineating continents, countries and oceans, the maps I grew up with, can be less important than the new maps of information flows. These network maps are generated by data scientists. They call the process surfacing. One takes a keyword, a message, a narrative and casts it into the ever-expanding pool of the worlds data. The data scientist then surfaces the people, media outlets, social media accounts, bots, trolls and cyborgs pushing or interacting with those keywords, narratives and messages.These network maps, which look like fields of pin mould or photographs of distant galaxies, show how outdated our geographic definitions are, revealing unexpected constellations where anyone from anywhere can influence everyone everywhere. Russian hackers run ads for Dubai hookers alongside anime memes supporting far-right parties in Germany. A rooted cosmopolitan sitting at home in Scotland guides activists away from police during riots in Istanbul. ISIS publicity lurks behind links to iPhonesRussia, with its social media squadrons, haunts these maps. Not because it is the force that can still move earth and heaven as it could in the Cold War, but because the Kremlins rulers are particularly adept at gaming elements of this new age, or at the very least are good at getting everyone to talk about how good they are, which could be the most important trick of all. As I will explain, this is not entirely accidental: precisely because they had lost the Cold War, Russian spin doctors and media manipulators managed to adapt to the new world quicker than anyone in the thing once known as the West. Between 2001 and 2010 I lived in Moscow and saw close up the same tactics of control and the same pathologies in public opinion which have since sprouted everywhere.But as this book travels through information flows and across networks and countries it also looks back in time, to the story of my parents, to the Cold War. This is not a family memoir as such; rather, I am concerned with where my familys story intersects with my subject. This is in part to see how the ideals of the past have fallen apart in the present and what, if anything, can still be gleaned from them. When all is swirling I find myself instinctively looking back, searching for a connection with the past in order to find a way to think about the future.But as I researched and wrote these sections of family history I was struck by something else: the extent to which our private thoughts, creative impulses and senses of self are shaped by information forces greater than ourselves. If there is one thing Ive been impressed with while browsing the shelves in the spiral-shaped library of my university, it is that one has to look beyond just news and politics and also consider poetry, schools, the language of bureaucracy and leisure to understand, as French philosopher Jacques Ellul put it, the formation of mens attitudes. This process is sometimes more evident in my family, because the dramas and ruptures of our lives makes it easier to see where those information forces, like vast weather systems, begin and end.Freedom of speech versus censorship was one of the clearer confrontations of the twentieth century. After the Cold War, freedom of speech appeared to have emerged victorious in many places. But what if the powerful can use information abundance to find new ways of stifling you, flipping the ideals of freedom of speech to crush dissent, while always leaving enough anonymity to be able to claim deniability?The Disinformation ArchitectureConsider the Philippines. In 1977, as my parents were experiencing the pleasures of the KGB, the Philippines was ruled by Colonel Ferdinand Marcos, a US-backed military dictator, under whose regime, a quick search of the Amnesty International website informs me, 3,257 political prisoners were killed, 35,000 tortured and 70,000 incarcerated. Marcos had a very theatrical philosophy of the role torture could play in pacifying society. Instead of being merely disappeared, 77 per cent of those killed were displayed by the side of roads as warnings to others. Victims might have their brains removed, for example, and their empty skulls stuffed with their underpants. Or they could be cut into pieces, so one would pass body parts on the way to market. Marcoss regime fell in 1986 in the face of mass protests, the US relinquishing its support and parts of the army defecting. Millions came out on the streets. It was meant to be a new day: an end to corruption, an end to the abuse of human rights. Marcos was exiled and lived out his last years in Hawaii.Today Manila greets you with sudden gusts of rotting fish and popcorn smells, wafts of sewage and cooking oil, which leave you retching on the pavement. Actually, pavement is the wrong word. There are few, in the sense of broad walkways where you can stroll. Instead, there are thin ledges that run along the rims of malls and skyscrapers, where you inch along beside the lava of traffic. Between the malls the city drops into deep troughs of slums, where at night the homeless sleep encased in silver foil, their feet sticking out, flopped over in alleys between bars boasting midget boxing and karaoke parlours where you can hire troupes of girls, in dresses so tight they cling to their thighs like pincers, to sing Korean pop songs with you.During the day you negotiate the spaces between mall, slum and skyscraper along elevated networks of crowded narrow walkways that are suspended in mid-air, winding in between the multistorey motorways. You duck your head to miss the buttresses of flyovers, flinch from the barrage of honks and sirens below, suddenly finding yourself at eye level with a pumping train or eye to eye with the picture of a woman eating Spam on one of the colossal advertising billboards. The billboards are everywhere, separating slum from skyscraper. Between 1898 and 1946 the Philippines was under US administration (apart from the Japanese occupation between 1942 and 1945). US navy bases have been present ever since, and US military food has become a delicacy. On one poster a happy housewife feeds her handsome husband tuna chunks from a tin. Elsewhere a picture of a dripping, roasting ham sits over a steaming river in which street kids swim; behind them an electric sign flashes Jesus Will Save You. This is a Catholic country: three hundred years of Spanish colonialism preceded Americas fifty (We had three hundred years of the Church and fifty years of Hollywood, Filipinos joke). The malls have churches you can worship in and guards to keep out the poor. Its a city of twenty-two million with almost no notion of common public space. Inside, the malls are perfumed with overpowering air freshener: lavender in the cheaper ones with their fields of fast-food outlets; a lighter lemon scent in the more sophisticated. This makes them smell like toilets, so the odour of the latrine never leaves you, whether its sewage outside or the malls inside.Soon you start noticing the selfies. Everyone is at it: the sweaty guy in greasy flip-flops riding the metal canister of a public bus; the Chinese girls waiting for their cocktails in the malls. The Philippines has the worlds highest use of selfies; the highest use of social media per capita; the highest use of text messages. Some put this down to the importance of family and personal connections as a means of getting by in the face of ineffective government. Nor are the selfies narcissistic necessarily: you trust people whose faces you can see.And with the rise of social media the Philippines has become a capital for a new breed of digital-era manipulation.I meet with P in one of the oases of malls next to sky-blue-windowed skyscrapers. He insists I cant use his name, but you can tell hes torn, desperate for recognition for the campaigns he cant take credit for. Hes in his early twenties, dressed as if he were a member of a Korean boy band, and whether hes talking about getting a president elected or his Instagram account registered with a blue tick (which denotes status), theres almost no change in his always heightened emotions.Theres a happiness to me if Im able to control the people. Maybe its a bad thing. It satisfies my ego, something deeper in me Its like becoming a god in the digital side, he exclaims. But it doesnt sound creepy, more like someone playing the role of the baddie in a musical farce.He began his online career at the age of fifteen, creating an anonymous page that encouraged people to speak about their romantic experiences. Tell me about your worst break-up, he would ask. What was your hottest date? He shows me one of his Facebook groups: it has more than three million members.While still at school he created new groups, each one with a different profile: one dedicated to joy, for example, another to mental strength. He was only sixteen when he began to be approached by corporations who would ask him to sneak in some mentions of their products. He honed his technique. For a week he would get a community to talk about love, for example, who they cared about the most. Then he would move the conversation to fear for your loved ones, the fear of losing someone. Then he would slide in a product: take this medicine and it will help extend the lives of loved ones.He claims that by the age of twenty he had fifteen million followers across all the platforms. The modest middle-class boy from the provinces could suddenly afford his own condo in a Manila skyscraper.After advertising, his next challenge was politics. At that point, political PR was all about getting journalists to write what you wanted. What if you could shape the whole conversation through social media?He pitched his approach to several parties, but the only candidate who would take P on was Rodrigo Duterte, an outsider who looked to social media as a new route to victory. One of Dutertes main selling points as a candidate was busting drug crime. He even boasted of driving around on a motorcycle and shooting drug dealers while he was mayor of Davao City, down in the deep south of the country. At the time, P was already in college, attending lectures on the Little Albert experiment from the 1920s, in which a toddler was exposed to frightening sounds whenever he saw a white rat, leading to him being afraid of all furry animals. P says this inspired him to try something similar with Duterte.First, he created a series of Facebook groups in different cities. They were innocuous enough, just discussion boards of what was on in town. The trick was to put them in the local dialect, of which there are hundreds in the Philippines. After six months, each group had in the region of 100,000 members. Then his administrators would start posting one local crime story per day, every day, to coincide with peak Internet traffic. The crime stories were real enough, but then Ps people would write comments that connected the crime to drugs: They say the killer was a drug dealer, or This one was a victim of a pusher. After a month they dropped in two stories per day; a month later, three per day.Drug crime became a hot topic, and Duterte drew ahead in the polls. P says this is when he fell out with the other PR people in the team and quit to join another candidate. This one was running on economic competence rather than fear. P claims he managed to get his rating up by more than five points, but it was too late to turn the tide and Duterte was elected president. Now he sees any number of PR people taking the credit for Duterte, and it riles him.The trouble with interviewing anyone who works in this world is that they always tend to amplify their impact. It comes with the profession. Did P create Duterte? Of course not. There would have been many factors that drove the conversation about drug crime, not least Dutertes own pronouncements. Nor was busting drug crime Dutertes only selling point: I have talked to supporters of his who were attracted by the image of a provincial fighting the elites of Imperial Manila and the prim Catholic Church establishment. But Ps account of digital influence does echo some academic studies.In Architects of Networked Disinformation, Dr Jonathan Corpus Ong of the University of Massachusetts and Dr Jason Cabaes of Leeds University spent twelve months interviewing the protagonists of what Ong called Manilas disinformation architecture, which was made use of by every party in the country. At the top were what he described as the chief architects of the system. They came from advertising and PR firms, lived in sleek apartments in the skyscrapers and described their work in an almost mythical way, comparing themselves to characters from the hit HBO fantasy TV seriesNext pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «30 July»

Look at similar books to 30 July. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book 30 July and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.