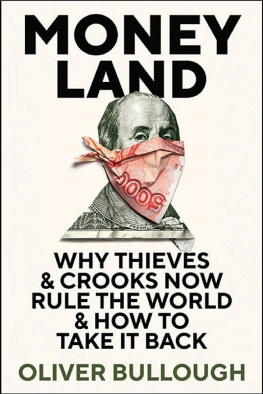

MONEY LAND

Corruption undermines democracy, weakens institutions and erodes trust, it destroys lives and impoverishes millions. Moneyland starts from that truth and tells Londons part of that story. Bulloughs book is an important challenge to our government, banks, law firms and professional services companies for their role in tolerating and sometimes facilitating a system that robs the poorest and today even threatens our own countrys security. This important book shows clearly that foreign policy isnt about foreigners, its about us. Tom Tugendhat, Chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee

This is meticulously researched and engagingly told, and reveals the horror and scale of dirty money flowing around the world. The central role played by the UK and jurisdictions associated with the British family mean that every person concerned about corruption and fairness in the UK should read this book and then campaign and act. Margaret Hodge, Chair of the Public Accounts Committee

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Oliver Bullough, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 78283 333 8

CONTENTS

ALADDINS CAVE

When the French rebelled in July 1789 they seized the Bastille, a prison that was a symbol of their rulers brutality. When the Ukrainians rebelled in 2014, they seized Mezhyhirya, the presidents palace, which was a symbol of their rulers greed. The palaces expansive grounds included water gardens, a golf course, a nouveau-Greek temple, a marble horse painted with a Tuscan landscape, an ostrich collection, an enclosure for shooting wild boar, as well as the five-storey log cabin where the countrys former president, Viktor Yanukovich, had indulged his tastes for the over-blown and the vulgar.

Everyone had known that Viktor Yanukovich was corrupt, but they had never seen the extent of his wealth before. At a time when ordinary Ukrainians wealth had been stagnant for years, he had accumulated a fortune worth hundreds of millions of dollars, as had his closest friends. He had more money than he could ever have needed, more treasures than he had rooms for.

All heads of state have palaces, but normally those palaces belong to the government, not to the individual. In the rare cases Donald Trump, say where the palaces are private property, they tend to have been acquired before the politician entered office. Yanukovich, however, had built his palace while living off a state salary, and that is why the protesters flocked to see his vast log cabin. They marvelled at the edifice of the main building, the fountains, the waterfalls, the statues, the exotic pheasants. It was a temple of tastelessness, a cathedral of kitsch, the epitome of excess. Enterprising locals rented bikes to visitors. The site was so large that there was no other way to see the whole place without suffering from exhaustion, and it took the revolutionaries days to explore all of its corners. The garages were an Aladdins cave of golden goods, some of them maybe priceless. The revolutionaries called the curators of Kievs National Art Museum to take everything away before it got damaged, to preserve it for the nation, to put it on display.

There were piles of gold-painted candlesticks, walls full of portraits of the president. There were statues of Greek gods, and an intricate oriental pagoda carved from an elephants tusk. There were icons, dozens of icons, antique rifles and swords, and axes. There was a certificate declaring Yanukovich to be hunter of the year, and documents announcing that a star had been named in his honour, and another for his wife. Some of the objects were displayed alongside the business cards of the officials who had presented them to the president. They had been tribute to a ruler: down payments to ensure the givers remained in Yanukovichs favour, and thus that they could continue to run the scams that made them rich.

Ukraine is perhaps the only country on Earth that, after being looted for years by a greed-drunk thug, would put the fruits of his and his cronies execrable taste on display as immersive conceptual art: objets trouvs that just happened to have been found in the presidents garage. None of the people queuing alongside me to enter the museum seemed sure whether to be proud or ashamed of that fact.

Inside the museum there was an ancient tome, displayed in a vitrine, with a sign declaring it to have been a present from the tax ministry. It was a copy of the Apostol, the first book ever printed in Ukraine, of which perhaps only 100 copies still exist. Why had the tax ministry decided that this was an appropriate gift for the president? How could the ministry afford it? Why was the tax ministry giving a present like this to the president anyway? Who paid for it? No one knew.

In among a pile of trashy ceramics was an exquisite Picasso vase, provenance unknown. Among the modern icons there was at least one from the fourteenth century, with the flat perspective that has inspired Orthodox devotion for a millennium. On display tables, by a portrait of Yanukovich executed in amber, and another one picked out in the seeds of Ukrainian cereal crops, were nineteenth-century Russian landscapes worth millions of dollars. A cabinet housed a steel hammer and sickle, which had once been a present to Joseph Stalin from the Ukrainian Communist Party. How did it get into Yanukovichs garage? Perhaps the president had had nowhere else to put it?

The crowd carried me through room after room after room; one was full of paintings of women, mostly with no clothes on, standing around in the open air surrounded by fully clothed men. By the end, I lacked the energy to remark on the flayed crocodile stuck to a wall, or to wonder at display cabinets containing 11 rifles, 4 swords, 12 pistols and a spear. Normally, it is my feet that fail first in a museum. This time, it was my brain.

The public kept coming, though, and the queue at the gate stretched all the way down the road for days. The people waiting looked jolly, edging slowly forward to vanish behind the museums pebble-dashed pediment. When they emerged again, they looked ashen. By the final door was a book for comments. Someone had written: How much can one man need? Horror. I feel nauseous.

And this was only the start. Those post-revolutionary days were lawless in the best way, in that no one in uniform stopped you indulging your curiosity, and I exploited the situation by invading as many of the old elites hidden haunts as I could. One trip took me to Sukholuchya, in the heart of a forest outside Kiev. The sun beat down, casting mirages on to the tarmac, as the road dived deeper into the trees. Anton, my driving companion, who ran his own IT company before joining the revolution, stopped the car at a gate, stepped off the road into the undergrowth, rustled around and held up what hed found. The key to paradise, he said, with a lop-sided smile. He unlocked the gate, got back behind the wheel and drove through.

Next page