The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Detroit, Michigan, reigned for a long spell in the American imagination as the quintessential industrial American city. It was a city on the go, literally, with its commercial wheels spun by a booming economy fed by a smoothly running automobile industry. From 1914, when Henry Ford doubled the wages of his employees and offered them an unheard of $5.00 a day, to the mid-1970s, when a series of gasoline crises fueled the economy for foreign cars, Detroit was a model of American enterprise tied to an enormous cultural vitality. The artistic fertility of the city was best embodied in Berry Gordys Motown Records, whose artistic production was modeled, intriguingly enough, on the assembly lines that manufactured the citys fantastic cars. Even though the prosperity was never spread equally among the races, the plentiful work on the assembly line helped, if not to democratize capital, then at least to catapult thousands of black families into the middle class.

But while pockets of black communities flourished economically, overall political progress flagged. Automobile factories, which were converted into manufacturers of materials for the Second World War, drew nearly half a million people to the city between 1940 and 1943. Many of the migrants were white southerners who rolled into the city with a Jim Crow outlook, including deep-seated bigotry against blacks and shop-worn stereotypes of Negro life. Many black folk came toomy father and, much later, my mother among themsetting up fraught competition for jobs between blacks and whites. The booming economy absorbed much of the friction, and offset, to a degree, black political marginalization and de facto disenfranchisement, but the underlying tension sparked a race riot in 1943.

Nearly a quarter century later, in 1967, when another riot and rebellion jumped off, the citys morale and fortunes plummeted dramatically. White folk fled even faster to surrounding suburbs and collar counties, leaving Detroit to become, as it had been becoming for more than a decade, a black Mecca, and then, afterward, a black hole that crushed the citys economic life through deindustrialization and white flight. The election of Coleman Young, the citys first black mayor, in 1974, showcased the striking contrast between evolving black political power and collective white resentment.

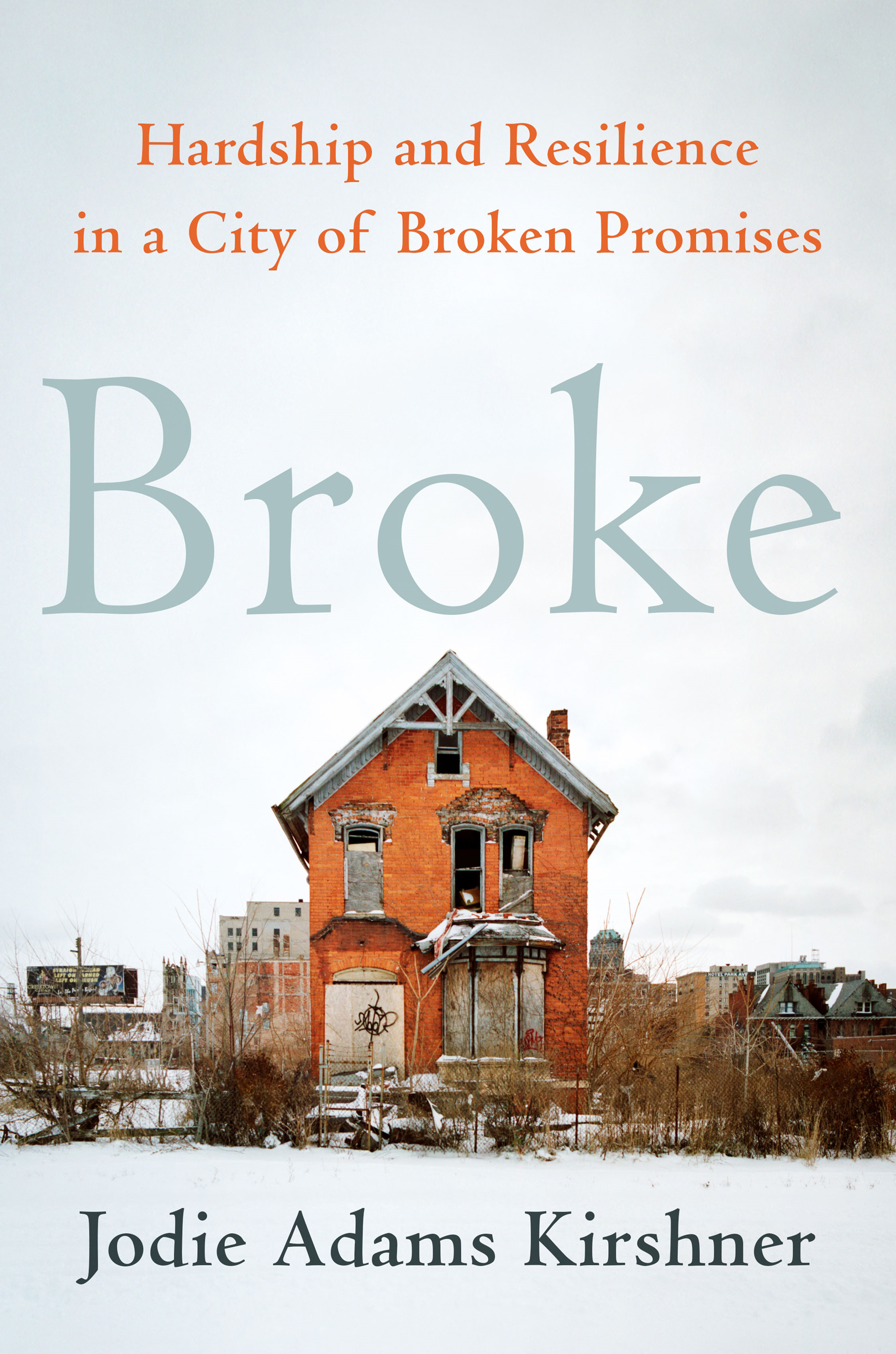

As Detroit got blacker and blacker, its economic prospects got bleaker and bleaker. Nationally, service industries supplanted manufacturing bases in a postindustrial surge that led, in relatively quick succession, to structural shifts in the economy, to the sputtering of the automobile industrywhich, presaging the fate of the city itself, saw Chrysler and GM declare bankruptcy in 2009to the citys credit rating sliding into junk territory. At the same time, the citys colorful and controversial young black mayor, Kwame Kilpatrick, succumbed to political self-destruction, the citys economy underwent further restructuring, and later, the automobile industry was bailed out by President Obama. But, perhaps most fatefully, ignominiously, and to many, unjustly, Governor Rick Snyder, embracing a jilting neoliberal politic, plunged Detroit into bankruptcy, making even more precarious the political and economic standing of its mostly black citizens. In so many ways, as Jodie Adams Kirshner says in the title of this arresting and affecting book, the city was just plain broke.

Broke exposes our stark neoliberal nightmare for what it truly isa socially depraved ideology that touts the free market as the ultimate solution for the various problems that it helps to create, including shifts in the auto industry, automations impact on labor, and the housing and mortgage crises. Too often critics and analysts find false consolation in data to grapple with these economic trends and troubles. To be blunt, many of us are enamored with statistics. A more dramatic analytical framework and a far more compelling moral response are required. Brokes narrative offers just that. Its case-study style snatches off the convoluted cloak of data to reveal the deep and personal scarring of an American urban community deliberately placed in a spiral of economic despair.

Detroits economic woes are not exclusively the result of political mismanagement. To be sure, that narrative is easier to digest than one that highlights the urban impact of post-industrialization, outsourcing, and the systematic privatization of public education. Those problems are real and have contributed to Detroits unique situation. Broke is at its thrilling best when it usefully mines the real-life experiences of Detroits gritty residents; it shines brightly when it depicts how residents are directly impacted by laws and policies that are crafted well beyond their municipal purview.

At times, Broke seems to be all about telling these individual storieshow Charles, Lola, or Miles wrestles with debilitating economic circumstances. At other times, Broke surveys the financial crises of a city under assault by shifting economic paradigms and predatory developers and their political enablers. But in the end, Broke isnt about how any of the enduring protagonists of Detroit are cash poor. Nor is it about the chronic financial woes of a city in intermittent financial disarray. Broke is about how the entire system of governance itself is broke.

Kirshner persuasively argues that the bankruptcy option for cities is a relatively new one, and a strategy that has largely proved ineffective. The option became viable in the late 1970s after federal, and by extension state, assistance to cities peaked. In 2013 Detroit became the largest American city ever to enter bankruptcy. More than 70 cities have followed that course since 2007. This isnt merely a Detroit problem, but, as Kirshner makes abundantly clear, one that looms large for dozens of other mostly urban communities vulnerable to a violent economic seizure and financial takeover. As it has done in other industrial pursuits, Detroit has sadly pioneered a troubling trend. The Motor City is a harbinger of the trauma to come.

Federal and state governments, agencies, and policies are just as responsible for the crisis in the American city as any local or city government. In the case of Detroit, federal and state governments, Republican and Democratic alike, have colluded to systematically defund and underfund the once teeming metropolis. It is an unquestionably tragic entry in the ledger of Americas vexed history with its urban centers. For example, in 2000, John Englerthe near Dickensian governor of Michigan who promoted an agenda of supply-side property tax cuts, privatization of state services, a hike in sales tax, and welfare and educational reformended the requirement for city workers to live within the citys limits. This had an immediate and deleterious impact on Detroit and its capacity to sustain its eroding tax base. At the same time, in a bitter irony, it subsidized the suburbs of Detroit from the new economy jobs in the 5 percent of Detroit that was in full recovery. To make matters worse, years later, neither Republican governor Rick Snyder nor Democratic president Barack Obama offered to bail out Detroit.