Contents

Guide

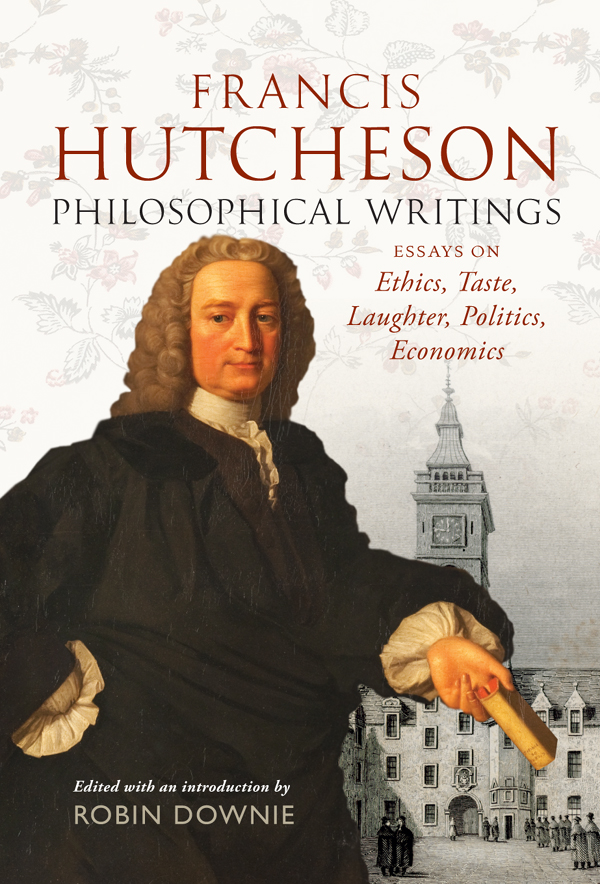

Francis Hutcheson

PHILOSOPHICAL

WRITINGS

The Lion and Unicorn staircase at the Old College, Glasgow University (Mirrorpix/Alamy)

First published by Everyman 1994

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2019 by

John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

ISBN: 978 1 788852 37 1

Preliminary material copyright Robin Downie 1994, 2019

The right of Robin Downie to be identified as the author of the preliminary material in his work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Philosophical interest in the Scottish Enlightenment was at one time limited to Book 1 of Humes Treatise on Human Nature, which was understood as an early version of logical positivism. But, since the second half of the twentieth century, interest in the Scottish Enlightenment has been growing, and editions and detailed analyses of its philosophers have appeared. As far as Francis Hutcheson is concerned there are now scholarly editions of his works edited by Knud Haakonssen and others, and there are also many detailed commentaries on these works. I list at least some of them in my bibliography. These works are for specialists. But there are many non-specialist philosophers who none the less would like to read for themselves the central themes in Hutchesons writings. This selection is for them.

There are three distinctive features of Hutchesons writings which I have tried to capture in my selections. First, his stress on the sentient side to human nature and its centrality in moral and aesthetic judgements represents a new and original departure for the philosophy of that period. It is a theme which continues to the present.

Secondly, although claims to historical priority are always contentious, there is a case for maintaining that his was the first philosophical treatise since Aristotle dealing in a perceptive way with questions of aesthetics and taste. And it is less contentious that Hutchesons three essays on laughter are still of interest. In our contemporary world many people are offended by some types of humour such as satire or caricature. Hutcheson offers an analysis of the moral rights and wrongs of humour. Certainly, his essays on laughter represent a totally new, original and insightful departure for philosophy. Moreover, as I try to bring out in my selection, many of the celebrated economic ideas of Adam Smith are to be found in Hutchesons works. Smith, of course, was one of Hutchesons students and always retained an admiration for him. In sum, Hutcheson made original contributions to philosophy of contemporary relevance, and has had a large influence on both the philosophy and economics of his successors, such as David Hume and Adam Smith. Indeed, he is mentioned not unfavourably by Kant.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, his influence extended internationally to the practical politics of North America. Hutchesons belief that natural rights belong equally to all led him to reject any form of slavery. This had an appeal to the abolitionist movement in North America, so it is not surprising that he was a highly influential and respected philosopher in eighteenth-century America. I have selected texts to bring out that Hutchesons appeal and influence extended beyond what we would nowadays think of as professional philosophy and are relevant to the political movements of his time, and indeed of our time. There cannot be many philosophers who are read by presidents of the United States, but consider the entry of 16 January 1756 in the diary of John Adams of Massachusetts, the second president of the United States: A fine morning. A large white frost upon the ground. Reading Hutchesons Introduction to Moral Philosophy. It is also arguable that Thomas Jefferson, the third president, was influenced by Hutcheson, specifically in his approach to the Revolution of 1776. I have said that my selection is for the mainstream philosopher rather than the historical specialist. Perhaps it is unrealistic to say it is also for presidents! But I hope at least that it will be of interest to political theorists and economists as well as philosophers.

Robin Downie

University of Glasgow, 2019

NOTE ON THE AUTHOR AND EDITOR

FRANCIS HUTCHESON was born 8 August 1694 in Drumalig in Northern Ireland, the second son of John Hutcheson, an Irish Presbyterian minister of Scottish parentage. After early education in Northern Ireland he attended Glasgow University where he studied philosophy and theology. On his return to Ireland in about 1717 he was licensed as a preacher but soon turned to an academic career. He was invited to Dublin to run a dissenting academy, i.e. an academy for those not eligible for the Irish University. This period (17219) was the most productive in Hutchesons life. The works he wrote then constitute his major achievement and he continued to revise them until the end of his life. In 1730 he took up the Chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University where he played an important role as a teacher and in liberalising the University. His influence on the Scottish Enlightenment and on thinkers and institutions in Europe and North America was enormous. He married in 1725 and was survived by a son who became Professor of Chemistry at Trinity College, Dublin. Hutcheson died of a fever in 1746 on a visit to Dublin where he is buried.

ROBIN DOWNIE is Emeritus Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, where his predecessors include Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith and Thomas Reid. In his many writings on the history and theory of moral philosophy, the arts, and the philosophy of medicine he has attempted to follow the example of his distinguished predecessors and reach the non-specialist reader.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For the Everyman edition (1994)

I owe an intellectual debt to the Hutcheson scholarship of Professors Peter Kivy, Bernard Peach and David Raphael. In particular, the teaching of David Raphael first created my interest in the British Moralists. The staff of the Special Collections at Glasgow University Library were helpful and prompt in answering my questions and obtaining editions for me. My colleague Elizabeth Telfer helped me to clarify the Introduction, and Professor David Walker advised me on Hutchesons jurisprudence. I am grateful to Natalina Bertoli, Carol Johnson and Andrea Henry for steering the book through the editorial processes, and to Lydia Rohmer and Carla Fassetta for help with proofs. Hilary Laurie and Dr David Berman of Everyman Library drew my attention to the need for a selection from Francis Hutcheson which would be usable by the non-specialist interested in the thought of the early eighteenth century. I hope the selection fulfils this need.