Thank you for buying this

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For those who care about all the creatures of this world, whether furry or fanged, slimy or scaly, majestic or misunderstood

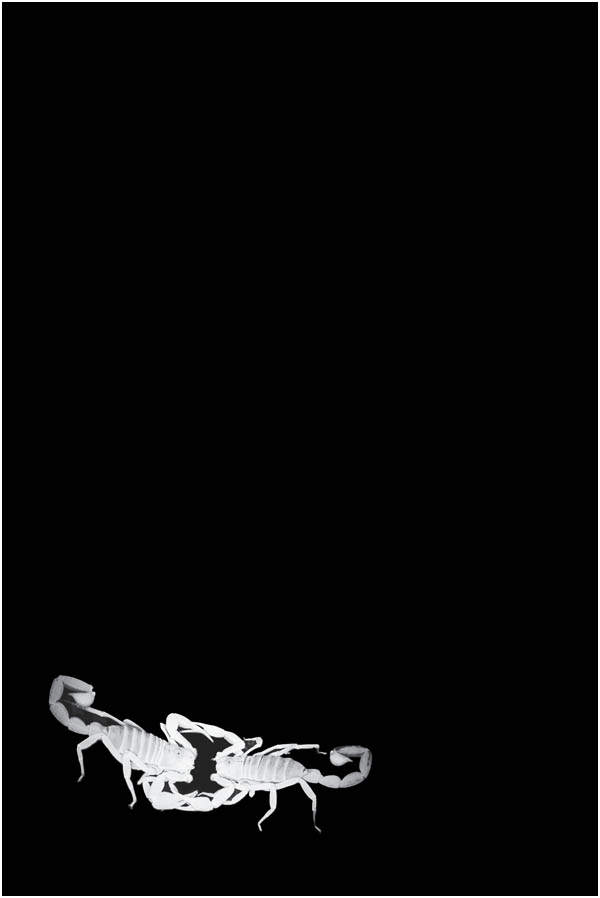

Before our species forged iron blades or wrote the first words, at a time when people cast aside their nomadic lifestyle in favor of settling down and began laying the foundations for the first civilizations; before the birth of Christ or Buddha, before Pythagorus or Archimedes, the people who lived in what is now Turkey built a temple. Today, it is known as Gbekli Tepe, which is Turkish for Potbelly Hill, and it is the oldest known religious site on earth. Dozens of large limestone pillars remain where devout believers carefully erected them more than one hundred centuries agotransported and raised by human hands alone, without the assistance of animals or even wheels. But you will find no angels or demons carved into these holy pillars. Instead, the ancient artists chose to decorate their most sacred temple with what they held most dear: the animals relevant to their daily lives, including venomous snakes, spiders, and scorpions.

There is no doubt that venomous animals share with us a deep, rich, and colorful history. They are ever-present in our existence: fear of many of them is innate in humans, found even in the youngest babes; they are vibrant and terrifying in the myths and legends of our tribes and civilizations; and from the dawn of recorded history, we have woven them into our culture. In a way, this book is my offering to these ancient godsmy ode to their fearsome power and my tribute to their incredible scientific potential.

My fascination with these creatures goes as far back as I can remember. When I was a kid, I lived in Kailua, Hawaii, and recall being transfixed by the blue bubbles of Portuguese man-of-wars that would wash up on the beaches near my home. They were just so pretty, so delicate, and I found myself drawn to them, prodding their translucent blue floats with anything I could get my tiny hands on. My fascination would not be deterred, not even after painful stings warned me of their dangerous nature. My compulsion has only deepened over time. When our family moved to Vermont, my mother nearly fainted when I showed her a snake I caught in the yard. During my freshman year of college, I was entranced by the upside-down jellyfish that we caught for our invertebrate zoology lab, and I spent the entire four-hour period gently flipping the creature to watch it swim or sink to the bottom of the glass dish. I kept at it, even as my fingers stiffened and eventually went numb from the mild venom. To this day I cant walk by a touch tank at an aquarium without pressing a finger against an anemone tentacle to feel it stick to my skin as it desperately tries but fails to penetrate my thick cuticle with its harpoon-like stinging barbs. I can spend hours petting the smooth wings of a stingray. I even decided to study the venomous lionfishes for my Ph.D.a move that my advisor found very amusing. We just finished a project on moray eels, he told me, with a mischievous glint in his eyes. Only three people got bitten. I cant wait to see how your project turns out.

Looking back, Im glad I chose venoms; my colleagues in this field are some of the most open, charming, and electrifying people on earth (though I may be somewhat biased). In my experience, there are two kinds of venom scientists. There are those you might consider lab ratsthe people whose initial interest in venoms stems not from the animals but from the molecular complexities present in their toxic secretions. Glenn King, professor of chemistry and structural biology at the University of Queensland and a leader in the search for potential venom pharmaceuticals, was an NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) structural biologist by training, and it was only when a colleague asked for help determining the structure of a venom toxin that he was lured into the field. Now hes at the forefront of venom bioprospecting, turning the venoms that harm into compounds that heal. Ken Winkel, the former director of the Australian Venom Research Unit at the University of Melbourne, readily admits that he isnt a snake guyhe came to study venoms almost by accident, as a byproduct of his initial interest in medical immunology. Similarly, the University of Utahs Baldomero (Toto) Olivera wanted to study neurons and paralysiscone snails just happened to be a way to do that.

Then, of course, there are the Bryan Frys of the world. Well, really, theres only one Bryan Fry. The head of the venom evolution lab at the University of Queensland is a unique character. National Geographic once described him as a ridiculously handsome adrenaline junkieI think of him as the bad boy of venom scientists. Hes not one to let others have all the fun, so he travels the world to catch and milk venomous animals, then uses a suite of modern tools to study the venoms from every angle. For his efforts, hes been bitten by twenty-six venomous snakes, broken twenty-three bones, and felt the painful venoms of three stingrays, two centipedes, and one scorpion. When I further inquired how many insects hed been envenomated by, he laughed. Who counts bees? You want me to count every fucking fire ant, too?

Bryan is blunt, brutally honest, perhaps even offensively straightforward. Hes also a brilliant scientist and one of the worlds experts on venoms. Ive known Bryan for years now; I met him when I was a young graduate student just starting on my study of the venomous lionfishes. While I was in Australia to get an up-close encounter with a platypus, I stopped by his lab at UQ, and we shared a pitcher of beer at the Red Room, the campus pub. I realized that although wed talked at length about various technical topics, Id never actually asked him what drove him to study venomous animals.

Its all Ive ever wanted to do, he said. Bryan is quick to admit that his study of venoms stems from his love of the animals. On his website, he confesses that while his research is important medically, it is all just a grand excuse to keep playing with these magnificent creatures! When he was four, Bryan announced proudly that he was going to work with venomous snakes for a livingand he meant it. Since then hes branched out: Bryan has studied anemones, centipedes, insects, fish, frogs, lizards, jellyfish, octopuses, salamanders, slow lorises, scorpions, spiders, and even venomous sharks. But while it was the animals that drew him to study venoms, its the venoms themselves that continue to stir his curiosity. What most intrigues him now about venom is, in his words, how many different flavors of fucked-up it can make you feel.

I, like Bryan and his kind of venom scientist, got into the study of venoms because of my love for the animals. But the more I learned about the intricate complexities of the chemical cocktails these animals produce, the more intrigued I was by the venoms themselves and the more I was drawn to the most dangerous of species. Even the most optimistic projection would suggest that my fascination with venomous animals is going to be a painful learning experience. But nothing worth anything comes without risk. What these animals have to teach us about ecosystems and how species interact is immeasurable; what we can learn about our own bodies from their potent toxins, invaluable; and what they tell us about the fundamental processes of evolution itself, inestimable. Ill happily risk a few ER visits for the opportunity to get a peek at what these animals have hidden in their genes, and to share their secrets with the world. So far, anyway, I have managed to travel around the globe and get up close and personal with a diversity of venomous animals, and Ive walked away unscathed.

Next page