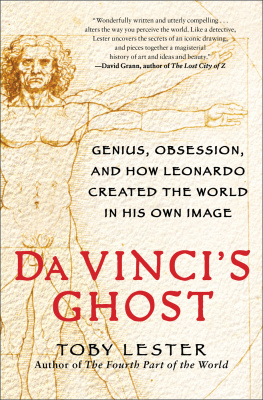

Toby Lester - Da Vinci’s Ghost

Here you can read online Toby Lester - Da Vinci’s Ghost full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Da Vinci’s Ghost

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Da Vinci’s Ghost: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Da Vinci’s Ghost" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Da Vinci’s Ghost — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Da Vinci’s Ghost" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

LEONARDO TIRELESSLY SOUGHT to learn from others as he pursued his own investigations, and in writing this book I tried to follow suit.

Im very grateful to Dr. Annalisa Perissa Torrini, the director of the Office of Drawings and Prints at the Gallerie dell Accademia in Venice, for allowing me an unforgettable private viewing of Vitruvian Man and for sharing with me her expert technical understanding of the drawing. Thanks also to Martin Clayton, the deputy curator of the Print Room at the Royal Library in Windsor, England, for giving me the chance to inspect firsthand some thirty of Leonardos original anatomical and proportional studies, a number of which are reproduced in this book. Speaking of illustrations: without the translation help so ably and amiably offered to me by Valentina Zanca, the publicist at Profile Books, the British publisher of this book, I would not have been able to negotiate the bureaucratic demands and idiosyncrasies of the many Italian libraries from which I acquired images for this book.

I owe a special debt to three scholars without whose private counsel, published writings, and spirit of generosity this book would have been much diminished. Indra Kagis McEwenan adjunct professor of art history at Concordia University, in Montreal, and the author of the remarkable study Vitruvius: Writing the Body of Architecture, from which much of my first chapter derivesopened my eyes to the richness of the world described and inhabited by Vitruvius, and then did her best to keep me honest as I distilled her ideas into dramatically reduced form. Richard Schofield, a professor of architectural history at the Istituto Universitario di Architettura, in Venice, provided all sorts of help: by offering expert perspective on the architectural environment in which Leonardo worked in the 1480s and 1490s; by translating several original fifteenth-century documents for me from Latin and Italian into English; by reading and commenting on a full early draft of this book; and, perhaps most important, by plying me with Chianti, pizza, and an evidently bottomless supply of sardonic wit during the two research visits I made to Venice. Finally, the architect Claudio Sgarbi introduced me to the remarkable drawing of Vitruvian Man that he discovered in Ferrara, shared with me his new findings about the drawings origins, and selflessly located and translated rare documents for me in the Biblioteca Comunale dell Archiginnasio, in Bolognaall while already fully occupied teaching architectural history and theory to Carleton University students in Ottawa and Bologna.

Im also grateful to the following people, many of whom I approached out of the blue, for their advice and assistance: Carl Barnes, Yelitza Claypoole, Susan Dackerman, Claire Farago, Gregory Guzman, Christine Johnson, Martin Kemp, Matthew Landrus, Domenico Laurenza, An Mertens, Rebecca Price, Jasper van Putten, Christine Smith, Ted Widmer, Mark Wilson Jones, Frank Zllner, and Robert Zwijnenberg. Thanks especially to Daniel Crewe, Alison Lester, Valerie Lester, Cullen Murphy, and Steven Schlozman, each of whom read part or all of this book in early form and provided valuable comments and criticism. Robb Menzi, Bill Pistner, and Chris Stone, for their part, continued to provide critical periods of subzero perspective. Any errors of fact or judgement that remain in this book, of course, are entirely my own.

In writing this book I worked with the same publisher, Free Press, that I worked with in writing my previous book, The Fourth Part of the World. I cant imagine a more professional and collegial publishing team than the one at Free Press, and I owe special thanks to many of its members: to Hilary Redmon, my terrific editor, whose critical eye and supportive nature have helped improve both of my books immeasurably; to Sydney Tanigawa, for so ably standing in for Hilary during her absence, and for shepherding this book through production; to Dominick Anfuso and Martha Levin, for their continuing interest in my work; to Ellen Sasahara for her wonderfully sensitive touch as a designer; and to Jocelyn Kalmus, for her help with publicity and her unflagging good cheer in confronting the not insubstantial challenges of promoting a book about really old pictures and ideas. Thanks also to Lynn Anderson, this books copy editor, for her thoughtful and meticulous attention to so many tiny details.

My literary agent, Rafe Sagalyn, helped me develop and shape the idea for this book, and then provided judiciously timed dollops of encouragement, perspective, and advice while I was working on it. The same goes for Valerie Lester, Alison Lester, and Jane Lester, who all lived through a lot with me during the period I was writing the book. My daughters, Emma, Kate, and Sage, increasingly busy with their own lives, kept me grounded at home and did their best to ensure I wouldnt finish this book too quickly. And then theres my wife, Catherine Claypoolewho, while raising our girls with me and holding down a demanding day job that never stops expanding, also lived through the writing of this book with me day by day and helped me with it in more ways than I can possibly express. All I can say is this: more than fifteen years in, I still feel like the luckiest man alive for having found her.

Finally, a cosmic shout-out to my father, Jim Lester, who died while I was writing this book. He was, and will always be, my favorite Renaissance Man.

BODY OF EMPIRE

I observed to be useful, and brought it together as a single body.

Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture (c. 25 B.C.)

MARCUS VITRUVIUS POLLIO was an army man, a cog in the great lumbering Roman war machine.

For years, assigned to the staff of Julius Caesar and other generals, he rumbled around Italy and the provinces, transporting equipment, fording rivers, pitching camps, digging ditches, sinking wells, constructing catapults, fighting battles, repairing siege engines, surveying captured land, laying out towns, founding colonies. Toiling away behind the scenes, he saw to it that everything worked. His efforts helped ensure victory and prosperity for Rome, and allowed his superiors to bask in fame and glory.

That seems to have struck him as not quite fair. In the mid-20s B.C., having retired from active duty, he looked back on his , he lamented. I am unknown to most people.

But his working life wasnt yet over. He still had time to make a name for himself and had even decided how he would do it. He would write a booka how-to guide to the building of empire.

VITRUVIUS DIDNT MAKE that decision in a vacuum. In the early 20s B.C., he and other Romans had watched with a mix of apprehension and pride as a canny new consul named Gaius Octavius Thurinus had asserted his grip on their capital city. In the previous decade Octavius, not yet forty, had avenged the murder of his uncle Julius Caesar and defeated his own archrival, Mark Antony, in Egypt, at last bringing to an end years of devastating civil war. Not long after returning home he had assumed a grand new name, Caesar Augustus, and had dedicated himself to the restoration of Rome. And then, as Vitruvius no doubt observed with delight, he had proceeded to launch the greatest building campaign the world had ever known, one that would fundamentally remake the city of Rome, transform the nature of Roman power and government, and redefine the very idea of empire. It was a campaign that in many ways gave lasting shape to what is today often described as the Western world.

Alive with resonances, the name Augustus inspired confidence. It meant stately, dignified, and holy: in a word, august. It implied an association with augurium (augury), the art of interpreting divine omens, which had long formed the bedrock on which Roman political, civic, and religious life was built. It also broadcast connections with

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Da Vinci’s Ghost»

Look at similar books to Da Vinci’s Ghost. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Da Vinci’s Ghost and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.