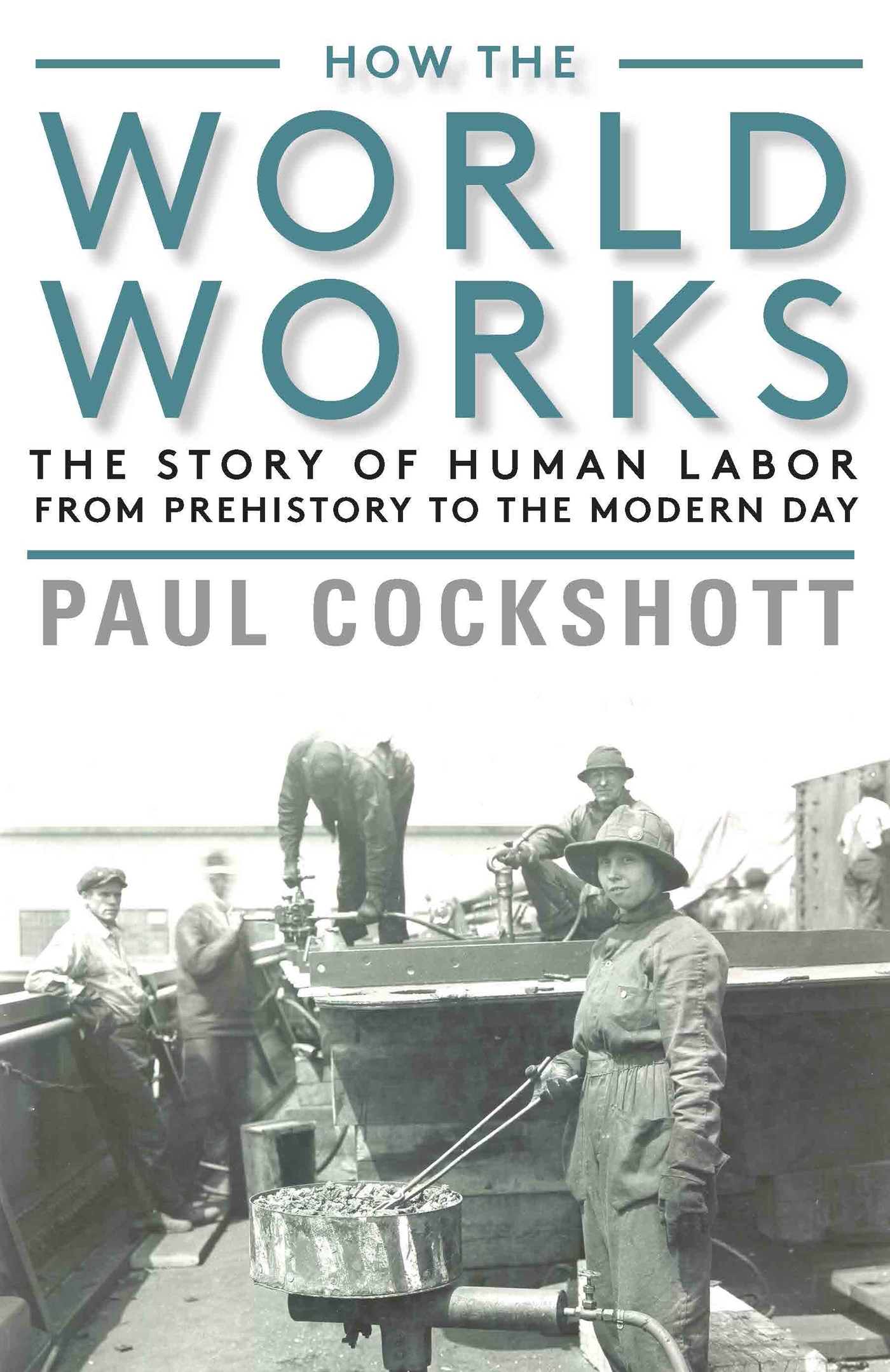

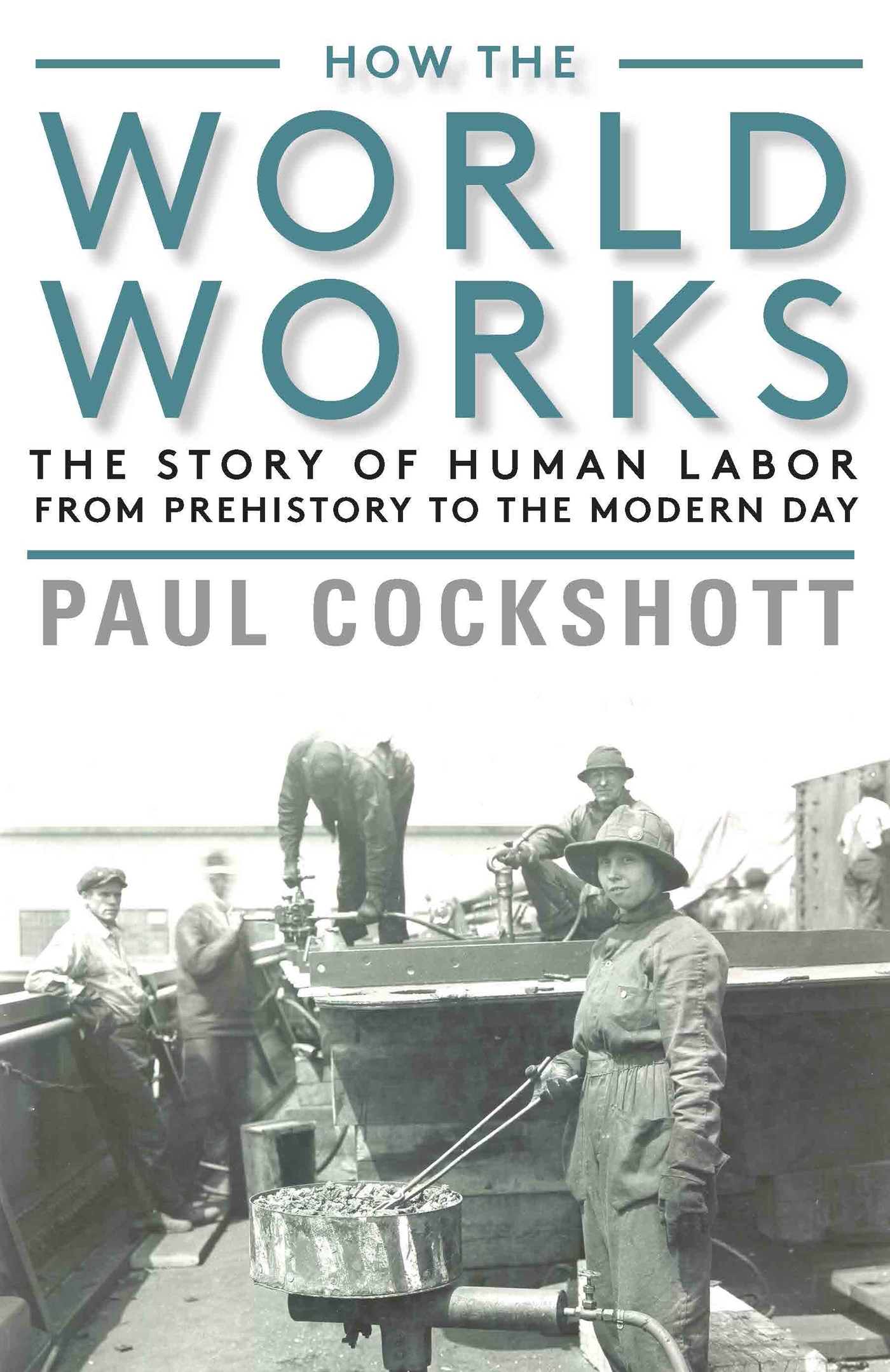

HOW THE WORLD WORKS

HOW THE

HOW THE

WORLD WORKS

THE STORY OF HUMAN LABOR

FROM PREHISTORY TO THE MODERN DAY

PAUL COCKSHOTT

MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS

New York

Copyright 2019 by Paul Cockshott

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

from the publisher

MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS, NEW YORK

monthlyreview.org

Typeset in Minion Pro and Brown

5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface for the General Reader

T his book has an ambitious scope, ranging as it does from pre-history to a future postfossil fuel era.

I wrote it because there is a lack, as far as I am aware, of a recent introduction to the materialist theory of history. Although it is not a history book, it is about the successive economic and social forms within which our history has taken place. I follow the approach pioneered by Adam Smith and Karl Marx of seeing history as being structured by the successive forms of economy within which people have worked to win their survival. I draw on the work of generations of historians, economists, and social theorists who have contributed to this materialist view of history, and I attempt to summarize their results for the non-specialist reader.

There are certain broad themes in my account: the interaction of human reproduction with technology, social domination, and the division of labor. In I look at the biggest change human society ever went through as we developed from being hunters to becoming farmers. We will see how, according to modern research, this transition was neither easy nor immediately beneficial, so the problem is to understand why it took place at all. But, once the transition took place, the additional food resources that became available allowed a dramatic rise in population density and to a process of migration and colonization that have left their marks in the languages we still speak.

While archaeology shows that the first agricultural societies retained an egalitarian structure, this had by the era of classical civilization thoroughly broken down. In area after area, freedom gave way to slavery. Slaves were forced to produce surplus goods for sale giving rise to international trade, the internal structure of slave economies, their markets and processes of reproduction and how their limited markets and their squandering of human resources led them to stagnate.

Since it was slave economies that invented money explains the classical theory of price, according to which the prices of commodities tend to be proportional to the amount of labor expended making them. In the process I explain how the classical theory is more scientific than the supply and demand theory that most social science students have been taught.

Slave economies have arisen at different times in various parts of the world, but in the end they have given way to peasant economies. In these, relatively self-sufficient family farms are subject to the exploitation a landlord or military class. In I look at the basic reproduction process of such economies, the degree of exploitation to which the peasants were subjected, and the efficiency of the overall economic model. In particular I am concerned to counter the modern prejudice that assumes feudal society to have been inefficient and irrational compared to modern capitalism.

Most of the world now lives in the capitalist economic system. , the longest in the book, explains how capitalism works. I show that the classical theory of price still applies under capitalism, and that this, combined with the existence of private firms, necessarily implies that goods will be sold at a markup or profit over the wage cost of their production. I show that it was ultimately the development of technology, particularly powered machinery, that enabled the owners of such machines to become the new dominant class. A large part of the chapter is devoted to the interaction between technology, profits, and real wages. I show that a freer and better paid workforce led to a more rapid rate of technical progress.

The next big theme of is how capitalism has interacted with population growth and family structure. Early and late capitalist societies have radically different demographics. An exploding population in the nineteenth century fueled European settler colonialism. Now, in contrast, developed capitalist states are scarcely able to reproduce their workforces. This shift has led to chronically depressed profit rates and stagnant levels of investment. It presages an existential crisis for capitalism.

One of the more controversial points I make is that far from the early twenty-first century being a period of very rapid technical change, such advances are now much slower than they were in the twentieth century. This slowdown in technical progress is a mark of capitalism having passed its heyday.

For a century now, socialist economies have existed as an alternative to capitalism. examines the basic structure of socialism. I start with technology. Electricity, and lots of it, was seen as one leg of socialist transformation. The other leg was people and the number of people depended on birth rates, death rates, and family structures, all of which are covered in section 6.3.

In capitalist economies the surplus available for investment depends on private profits; in a socialist system it depends on the planned division of output between consumer goods and investment goods. In classical Marxist terms, socialist economies have a historically unique mechanism for the extraction of a surplus product. This mechanism underlay the very fast growth rates achieved by the USSR before the 1970s and by China right up until to the present. Section 6.5 presents the basic theory of socialist growth developed by Feldman in the 1920s and shows that his theory gives a good explanation of what was achieved over the next fifty years. What is not widely appreciated in the West was just how successful the USSR was in the production of mass consumption goods. Why, if it was producing so much, was there an impression of continuous shortages?

It comes down in the end to how the Soviets managed the consumer market, and, more fundamentally, to why there still was a market in consumer goods. The later parts of the chapter deal with why the socialist economies still retained money, and why it was impossible for them to escape what Marxists term the law of value. The chapter finishes with an examination of the processes that led to the final disintegration of the European socialist countries.

I finish with a chapter on future economies. I look at the constraints that will be imposed by a shift to carbon-neutral economics. I ask whether future economies will be communist and whether communism has some specific technical basis on which it must rest. This chapter is inevitably slightly speculative!

COMMENTS FOR MORE TECHNICAL READERS

Although this book is written from a perspective strongly influenced by Marx, there are a number of points on which my presentation will differ significantly from what has become common in Marxism.

The first difference is on the role assigned to technology. Back in the mid-nineteenth century Marx put forward a bold, technologically determinist view of society. But this view came to be seen as something of an embarrassment by the late twentieth century, particularly by European and American theorists. Western Marxist theory was dominated by people with a training in the humanities or social studies. Exceptions like Bernal, Bordiga, Pannekoek, or Machover were so few that their very existence was noteworthy. The specialized educational background of Western Marxists had a number of effects: slow adoption of new concepts from the sciences, hostility to what is seen as technical determinism and reluctance to use mathematical and quantitative methods.

Next page

HOW THE

HOW THE