Published by Lexington Books

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.lexingtonbooks.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2011 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dppe, Till, 1977

The making of the economy : a phenomenology of economic science / Till Dppe.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7391-6419-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7391-6954-4 (electronic)

1. EconomicsPhilosophy. 2. Structuralism. I. Title.

HB72.D74 2011

330.1dc23 2011031011

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Preface

T WO DECADES AGO, A BOOK CALLED The Making of an Economist appeared (1990). The authors, Arjo Klamer and David Colander, interviewed graduate students in economics from leading U.S. universities, showing how students were regularly frustrated with their studies. They could not live out their economic concerns in the discipline of economics. The book was a fine description of my experience as a young economics student in the 1990s.

In response to Klamer and Colanders work, as well as many other critiques of the intellectual culture in economics, the discipline has markedly changed during the last decades. It has changed to such an extent that David Colander became convinced that the discipline is back on track in being more eclectic about problems and less obsessed by deduction (2007). Arjo Klamer, who accompanied the PhD research preceding this book, has not given up skepticism, and began engaging in neighboring fields of economics.

The Making of the Economy gives a third reply to the discontent about the discipline of economics. It can be read as a historical supplement arguing that the very idea of relevant economic knowledge might have been a misunderstanding all along. When going back in the past, we learn to see the current complaints about economics as a side effect of economists attempts to gain authority by intellectual reticence. The belief in that thing called the economy is the result of this intellectual reticence.

Introduction

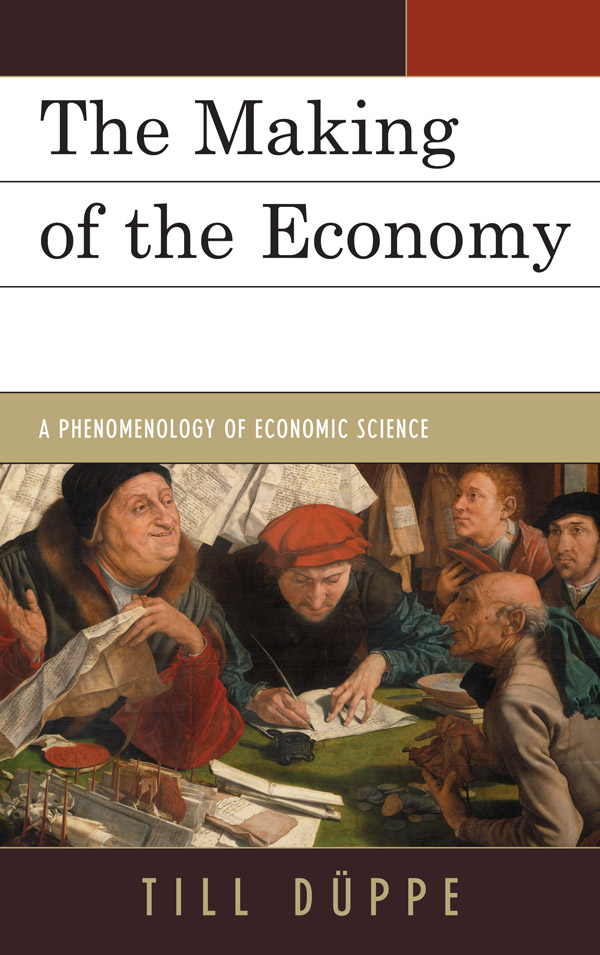

I N TRYING TO UNDERSTAND THE NATURE OF ECONOMIC discourse and the role that science plays in it, the Flemish painting on the front cover provides a first clue. It was painted by Marinus van Reymerswaele in 1542, and depicts three people negotiating about money: a well-fed man on the left, an old man at the bottom right, and a clerk in the center of the scene.

The painters sympathies clearly lie on the side of the old man. With eyes opened wide, he looks up pleadingly at his adversary. He displays his empty pouch timidly, his shame and vulnerability laid bare. For him, seemingly down on his uppers, there is much at stake. The Yes or No that the scene will arrive at will perhaps determine whether he and his family will have their daily bread, whether tomorrow will be another frightening ordeal. The old man feels the gravity of the encounter deep under his skin, down to his brittle bones and empty stomach. He is completely at the mercy of his adversarys mood. The old man in this image represents the pervasive motif of economic discourses: the urge for betterment, the necessity of the aid of others, the sense of immediate importance and relevance that most share when attending to economic conversations.

The well-fed man on the left takes up the most space and dominates the scene. He looks down at the old man with a contemptuous smile and casually guards the piece of paper in his hand, equivocating teasingly. Strictly speaking, he is the only one with any agency in the scene. He decides. He exerts power. Disturbingly, the moment of the encounter appears rather inconsequential to him. Other needy people are probably waiting in line. He seems to enjoy his position and plays with his ambivalence maybe yes, maybe no. The painting is named after him: The Tax Collector. The well-fed man was thus one of the officials sent by the Spanish crown to the rural areas of the Low Lands in order to collect taxes from the empires subordinates. The painter depicts him with the same sentiments with which others in medieval times had depicted usurersthe greedy persons. The only difference was that state authority was now under attack, from which the Dutch would free themselves during the Eighty Years War to come at the end of the sixteenth century. Liberation from those who exert powerwhatever it is that entitles them to do sowould be the political concern of all modern economic discourses on both libertarian and socialist fronts.

In the center of the painting is the clerk, looking down at his sheet as though he plays no role in the negotiation at all. He merely keeps records, drawing the lines between debits and credits, between claims and obligations. Being a simple functionary, he has to take considerable care not to make a mistake. Even a slight misstep could have fatal results. And so he scribbles his figures with the utmost concentration, as if with closed eyes. He knows the others concerns only from a distance, by the surface of his sheet rather than by their glances. As close as the others are, the clerk encounters none of them. Sitting between the tax collector and the old man, he tries to remain as aloof as possible.

The encounter is intricate: The old man, knowing in concrete terms the difference between Yes and No, may play down his doubts about his ability to keep his own promises. Since this is known to the others, the more he pleads, the less likely he appears to be worth the money, and the more haughty and amused the tax collector becomes. Having nothing left to give, the old man may ask to pay tomorrow. But how could the greedy official respond other than, Look at you! You said the same yesterday! And the old man would reply, Even if I pay today, you would charge me even more tomorrow. Just like yesterday! And the writer, how would he react? Between the gloating on one side and begging on the other, his main concern is his own accuracy. Hence, the more heated the argument, the more the clerk buries his head in his books. Reymerswaele, whatever sympathies he entertained, says one thing clearly: Deals involving money do not take place at eye level. Empathy or understanding seems impossible. The more the old man pleads, the more the greedy collector laughs, and thus the more the writer buries his head. Economic discourses, then and now are governed by suspicion.

Moreover, Reymerswaele clearly anticipated what would become the social role of economic scientists in economic discourse bred by the culture of suspicion. The economic scientist would emerge as the person in the center of the scene: not as the onlooker of people conducting their economic lives, but as the downlooker from a world in which truth claims are undermined by mutual suspicion. Economic science emerged in reaction to, and as a diversion from, the economic suspicion. The notion of economic knowledge as referring to actual truth is based on nothing but the impression made by those who remain silent while others yell: all that clamor, but the writer in the middle stays calm! Such perplexity is what makes people believe in the expertise of economists.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.