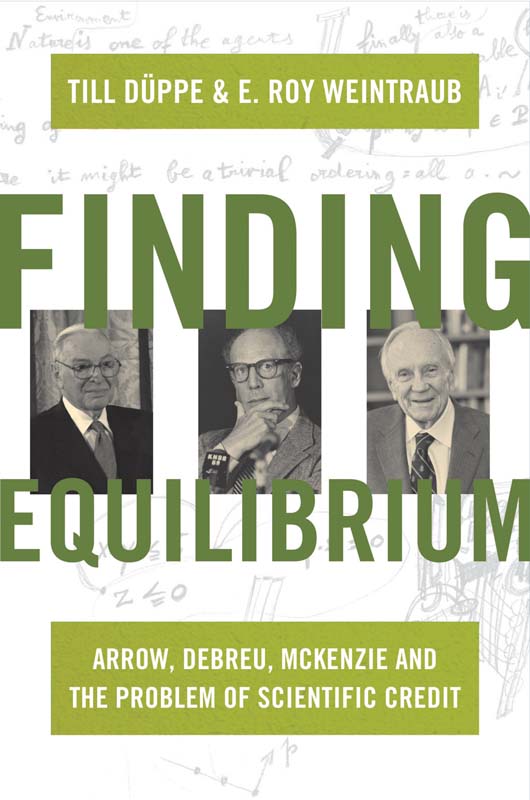

FINDING EQUILIBRIUM

FINDING EQUILIBRIUM

ARROW, DEBREU, MCKENZIE AND THE PROBLEM OF SCIENTIFIC CREDIT

TILL DPPE AND E. ROY WEINTRAUB

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket Photographs: Detail of Kenneth Arrow courtesy of the National Science and Technology Medals Foundation. Photograph of Gerard Debreu courtesy of Biblioteca Universidad de Alcal/D-Space/Creative Commons. Photograph of Lionel McKenzie courtesy of the University of Rochester. Background: Gerard Debreu papers, 19492001. Collection number BANC MSS 2006/218, Carton 8, research notes. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dppe, Till, 1977

Finding equilibrium : Arrow, Debreu, McKenzie and the problem of scientific credit / Till Dppe and E. Roy Weintraub.

pages cm

Summary: Finding Equilibrium explores the postWorld War II transformation of economics by constructing a history of the proof of its central dogmathat a competitive market economy may possess a set of equilibrium prices. The model economy for which the theorem could be proved was mapped out in 1954 by Kenneth Arrow and Gerard Debreu collaboratively, and by Lionel McKenzie separately, and would become widely known as the Arrow-Debreu Model. While Arrow and Debreu would later go on to win separate Nobel prizes in economics, McKenzie would never receive it. Till Dppe and E. Roy Weintraub explore the lives and work of these economists and the issues of scientific credit against the extraordinary backdrop of overlapping research communities and an economics discipline that was shifting dramatically to mathematical modes of expression. Based on recently opened archives, Finding Equilibrium shows the complex interplay between each mans personal life and work, and examines compelling ideas about scientific credit, publication, regard for different research institutions, and the awarding of Nobel prizes. Instead of asking whether recognition was rightly or wrongly given, and who were the heroes or villains, the book considers attitudes toward intellectual credit and strategies to gain it vis--vis the communities that grant it. Telling the story behind the proof of the central theorem in economics, Finding Equilibrium sheds light on the changing nature of the scientific community and the critical connections between the personal and public rewards of scientific workProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15664-4 (hardback)

1. Equilibrium (Economics) I. Weintraub, E. Roy. II. Title.

HB145.D87 2014

339.5dc23

2013050578

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro and Trade Gothic Lt Std.

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Harald, Brigitte, Jens, and Benjamin (TD)

For Lauren, David, Molly, Alexa, Nico, Lucie, Henry, and RJ (ERW)

In some ideal sense, life philosophies, like economies, may be refined by successive adjustments through reflection, experience, and intellectual interaction with the past and the present until they come into an equilibrium independent of initial conditions. In fact, neither is ever independent of history.

ARROW 1992, 43

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I think I finally understand the difference. We mathematical economists take a work, for example take Walras Elements, and put it in boiling oil until all there is left is the skeleton, its essence or true character. You historians are instead interested in the skin and the flesh.

WERNER HILDENBRAND

In the years following World War II, three mathematical economistsKenneth Arrow, Grard Debreu, and Lionel McKenzieput, in Hildenbrands words, economic theory in boiling oil and obtained one and the same skeleton: axiomatized general equilibrium theory. In their own histories, in their personal skin and flesh, they were as dissimilar as it was possible for economists to be in the mid-twentieth century.

Arrow grew up in immigrant Jewish New York. He was the precocious son of an established middle-class banker-lawyer who lost his job in the Depression and as a result the family found itself in greatly reduced circumstances during the 1930s. He was one of the Depression generations bright kids educated at City College of New York, where he graduated at the head of his class in 1939. His academic career was superlative. As an undergraduate he took mathematics courses and was asked by Alfred Tarski to check the English translation of his German-language book on logic (Tarski 1941, xiv). Wanting to learn more about statistics because he thought he might find employment eventually as an actuary, Arrow ended up at Columbia studying with the eminent economist Harold Hotelling. Although his studies were interrupted by wartime service in the U.S. Army Weather Corps, after the war Arrow was recommended by Hotelling to the Cowles Commission in Chicago in 1948. He was fast-tracked to the highest levels of what was to become a new mathematical economics.

In contrast to the precocious urban Arrow, Debreu grew up in provincial Calais, was orphaned at an early age, and was raised by relatives and boarding schools. Late in high school his intellectual prowess became apparent as he finished second in a nationwide competition, the concours gnral in physics. After a strong pre-baccalaureate career, his teachers encouraged him to take the special examinations that would lead to entrance into one of the Grandes coles. Debreu was sent to Vichy in the south of France for that special examination preparation and after two years succeeded in securing admission in 1942 to Lcole Normale Suprieure in Paris. His performance there was exemplary as he was taught by, and trained by, the very best mathematicians in France, particularly Henri Cartan among the emergent Bourbakiens. Following the Allied invasion in 1944, he served in the Free French Forces. After the war he sat his examinations and began thinking of ways to move away from mathematics and, serendipitously, made connection with Maurice Allais. Through Allaiss intervention Debreu secured a Rockefeller grant to travel to the United States, where he eventually took up a research position at Cowles in Chicago. Debreu was as austere as Arrow was boisterous, as controlled as Arrow was exuberant.

Lionel McKenzie, in further contrast, was a well-mannered son of the interwar American rural South. Both his mother and father were well educated for that time and place, and McKenzie enjoyed a normal, intellectually successful but unaccelerated boyhood. With modest family financial resources in the Depression he went to Middle Georgia College and after two successful years there secured admission and a scholarship to Duke University. At Duke he performed at the highest level, receiving all As in honors courses concentrating in politics, philosophy, and economics, ultimately becoming the class valedictorian. In spring 1939 he won a Rhodes Scholarship that would have taken him to Oxford for two years had World War II not broken out in September 1939. He entered military service in 1941, and on demobilization he went to Oxford. Returning from Oxford after two years, and having begun a teaching career at Duke, he learned that he had failed to achieve the Oxford D.Phil. degree. He was no longer on a fast track.

Next page