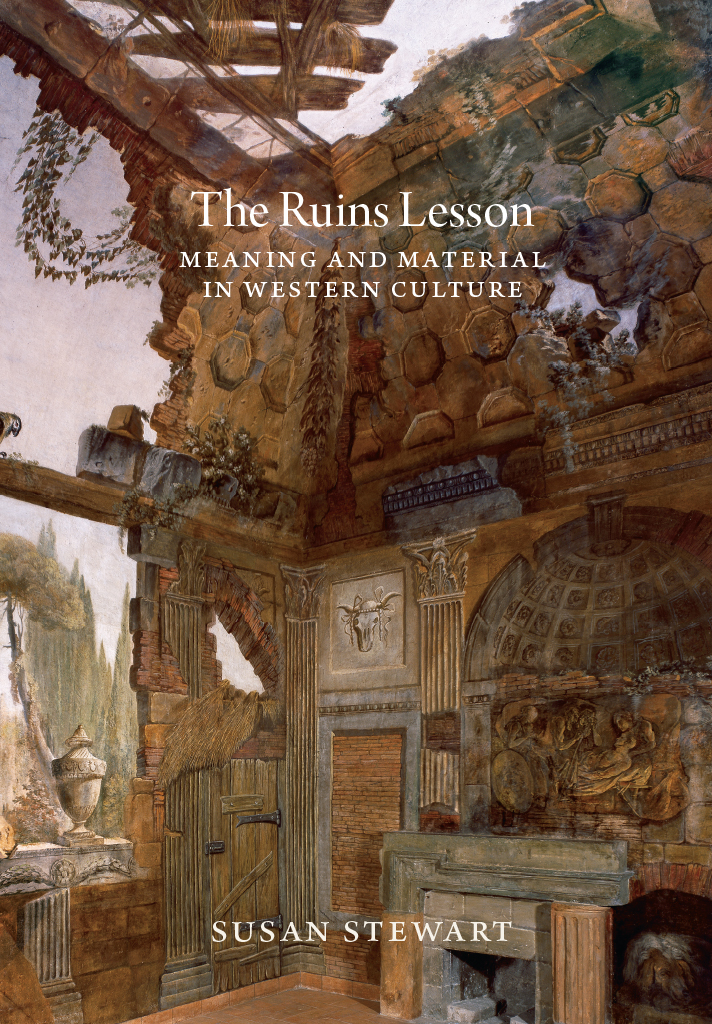

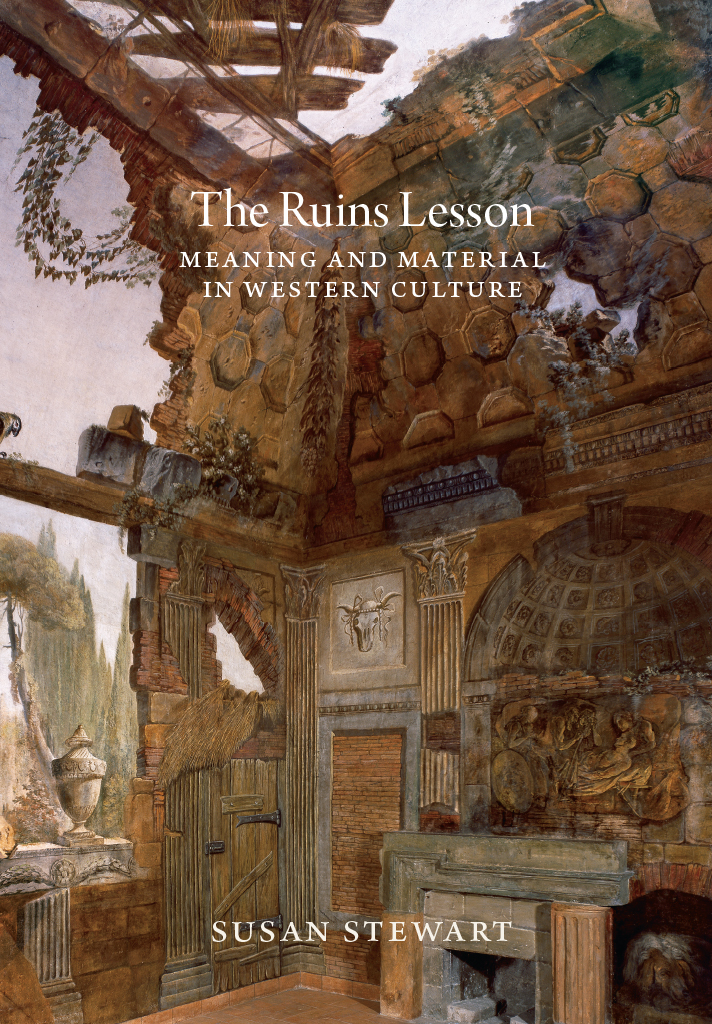

The Ruins Lesson

The Ruins Lesson

Meaning and Material in Western Culture

Susan Stewart

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-63261-2 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-63275-9 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226632759.001.0001

This publication is made possible in part by support from the Barr Ferree Foundation Fund for Publications, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stewart, Susan, 1952 author.

Title: The ruins lesson : meaning and material in western culture / Susan Stewart.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019030168 | ISBN 9780226632612 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226632759 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ruins in literature. | Ruins in art. | Antiquities in literature. | Antiquities in art.

Classification: LCC PN56.R87 S74 2019 | DDC 809/.9335dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019030168

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Alice, Leon, and Percy

new, tender, quick!

Contents

Valuing Ruin

This Ruined Earth

Inscriptions and Spolia

Nymphs, Virgins, and WhoresOn the Ruin of Women

Humanism and the Rise of the Ruins Print

The Architectural Imaginary

The Voyages and Fantasies of the Ruins Craze

On the Nonfinality of Certain Works of Art

The Decay of Monuments and the Promises of Language

Color Plates

Black-and-White Figures

Today, in what we call the developed world, we often pursue practices that undermine our values. We know that to survive as a species we must nourish the resources of the earth, yet we continue to further an economic system based upon creative destruction. We hold to a belief in the intrinsic worth of individuals, yet we further, through animosity or indifference alike, the physical and mental degradation of those who are impoverished and powerless. We pursue new knowledge, yet we crush its consequences by demanding it yield immediate, material benefit. Not only do we practice these and other forms of unmaking and destruction, we have also turned their image into a vital theme of our art tradition. Beyond expressing the contradictions of hypocrisy and greed, or the pressures arising from a death drive, there seems to be some sense of mastery, freedom, or even pleasure involved in the pursuit of representations of ruin. From stories of the fall of Troy to contemporary ruins porn, we so often are drawnin schadenfreude, terror, or what we imagine is transcendenceto the sight of what is broken, damaged, and decayed.

In this study, I have tried to understand the fascination and appeal of ruins throughout the history of Western art and literature. A scholar of other traditions, an economist, psychologist, historian, or anthropologist, would have looked elsewhere and along other paths. But I have considered works of art, in our time both revered for their metaphysical power and taken up as commodities for speculation, as paradigmatic of conflicts between beliefs and practices involving materialism and value. By representing what we find most compelling, and calling themselves for judgment and care, works of art tell us a great deal about our attitudes toward materiality. And in their autotelic discourse regarding form, formlessness, and significance, they are our most sustained meditation on the limits and possibilities of meaning.

My research has led me to founding legends of tragic flaws, broken covenants, and original sin; to the Christian rejection, appropriation, and transformation of the classical past; to myths and rituals regulating human fertility, and their consequences in the exaltation and disparagement of women; to the proliferation of ruins images in Renaissance allegory and eighteenth-century melancholy; to ancient sites of disaster and to gardens featuring new ruins. In their multiplication of ruins images, artists and writers have struggled to recover morals and lessons out of the fragility and inevitable mortality of intended forms. Beginning with ancient Egyptian memorials and ending in twentieth- and twenty-first-century responses to world war, I nevertheless focus on periods of intense interest in ruins and emerging paradigms for their receptionparticularly the era of Northern humanism in the Renaissance and the ruins craze of the eighteenth century and Romanticism. I return several times to a set of artists and writers whom I consider to be visionaries regarding ruins: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, William Blake, and William Wordsworth.

The reader will discover that this book is also a meditation on the story of the Tower of Babel. Ruins arise at the boundaries of cultures and civilizationssyncretic phenomena, their very appearance depends on an act of translation between the past and the present, between those who have vanished and those who have survived. Ruins are in this sense the alter egos of what is left unfinished, and they offer a warning to the makers of monuments. In the end, I have asked what cannot be ruined, and have found therein the eternal resources of thought and languagea means of addressing those contradictions with which I began.

Valuing Ruin

In Western culture, for better or worse, men and women have located themselves in time and space by marking the earth. The flags they plant, the dwellings they build, the tombs they place, the permanent settlements and cities they foundall mediate the relation between ground and sky, establishing their coordinates in line with those of rising and setting stars and recurring patterns of wind and weather. They yoke materials, plans, and, later, stories of their making, to the illusion of their permanence.

How is it, then, that ruins, those damaged and disappearing vestiges of the built environment, became so significant in Western art and literature? Derived from the Latin ruere, to fall or collapse, the word ruin is both a noun and a verb. As a noun, ruin refers to a fabric or being that is meant to be upright but has fallen, often headlong, to the ground. What should be vertical and enduring has become horizontal and broken. As a verb, ruin means to overthrow, to destroy, or, often in the case of a woman victim, to dishonor. Persons and things can be slowly ruined by suffering the depredations of use and ordinary weather, and in times of human violence and extreme weather, they can be actively ruined.

Nevertheless, at least since late antiquity, poets, thinkers, artists, and sometimes emperors have brought an array of positive attitudes toward ruins: in the first and second centuries CE , the elder Pliny and the far-ranging Lydian physician and traveler Pausanias looked on them with some measure of reverence and nostalgia. In the early Christian period, Roman ruins were used as quarries and, although they continued to fall into rubble well into the fifteenth century, we also find a growing interest in preserving their forms. At the turn of the thirteenth century, Frederick II incorporated their remains into his castles, and in the ensuing centuries, Petrarch hoped to animate them, Francesco Colonna wove them into architectural fantasies, and Raphael protected their inscriptions.Antwerp, Prague, Florence, and Rome allegorized and dreamed over them. Antiquarians and architects of the Enlightenment looked on them with both melancholy disenchantment and scientific curiosity. Romantic poets used them as scenes of writing and speculation. Ancient emperors and twentieth-century dictators alike have taken their persistence as self-justifying grounds for claims to power.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).