International acclaim for Christopher Woodwards

In Ruins

Intriguing. Woodwards enthusiasm for ruins is infectious.A fascinating tour.

San Francisco Chronicle

Brilliant, daring and evocative. The Guardian

Absorbing. Delightful. Woodward does a terrific job of showing us the variety of ways artifacts have been interpreted and treated over the years. In Woodward, [ruins] have an accomplished and eloquent spokesperson. The Providence Journal

A handsomely written, constantly surprising meditation upon ruins and the way they provide consolation in the face of so much human folly.

Daily News (New York)

An enchanting and informative voyage Fizzes with felicitous detail, anecdote, literary reference, and art history. Evening Standard

Beautifully written. Contains astonishing facts, interesting digressions, alluring illustrations and tantalizing references. An entertaining, even an endearing work.

Winston -Salem Journal

Fetching. Whimsical. Woodwards enthusiasms are catching.

The New York Observer

A thought-provoking grand tour of familiarand lesser-knownstops along the archaeological trail.

Archaeology

A picturesque hybrid of travelogue, personal memoir, lyric rhapsody, art history and cultural criticism. Woodwards meditation oscillates between bright fragments of insight and anecdotethey shimmer in fugitive attitudes, then slide into freshly provocative patterns, scattered over the tides of time by this seasoned tourist to historys shoreline.

Los Angeles Times Book Review

Nothing less than a guided tour of the worlds most celebrated ruins as well as a short history of the human intellect as it has contemplated these ruins.

The Tennessecm

Masterful. Well-illustrated. Constantly entertaining.

The Times (Trenton, NJ)

A thoughtful book. After reading it, no building will seem safe from times depredations.

Cond Nast Traveller

CHRISTOPHER WOODWARD

In Ruins

Christopher Woodward is the director of the Holburne Museum of Art in Bath, England, where he lives.

For Michael and Isabel Brings

For I know some will say, why does he treat us to descriptions of weeds, and make us hobble after him over broken stones, decayed buildings, and old rubbish?

Preface to A Journey into Greece

by George Wheeler (1682)

I

Who Killed Daisy Miller?

I n the closing scene of Planet of the Apes (1968) Charlton Heston, astronaut, rides away into the distance. What will he find out there? asks one ape. His destiny, replies another. On a desolate seashore a shadow falls across Hestons figure. He looks up, then tumbles from his horse in bewilderment. Oh my God! Im back. Im home. Damn you all to hell! You maniacs. They did it, they finally did it, they blew it up! The shadow is cast by the Statue of Liberty. She is buried up to her waist, her tablet battered, and her torch fractured. The planet of the apes is Earth, he realises, destroyed by a nuclear holocaust while the astronauts were travelling in space. He is the last man, and the lone and level sands stretch far away.

A century before the film was made, a man in a black cape sits on the arch of a ruined bridge. He holds an artists sketchbook as firmly as if inscribing an epitaph. Blackened shells of buildings rise at the marshy edge of a slow and reedy river, one faade advertising C OMMERCIAL W HARF . This is London or, rather, its future as imagined by the artist Gustave Dor in 1873. The wizard-like figure in Dors engraving is a traveller from New Zealand, for to many Victorians this young colony seemed to represent the dominant civilisation of the future. He sits on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St Pauls, exactly as Victorian Englishmen sketched those of ancient Rome. The cathedral-like ruin next to the commercial warehouse is Cannon Street Station, brand-new in 1873 but here imagined with the cast-iron piers of the bridge rusting away in the tidal ooze.

The New Zealander by Gustave Dor, from London, 1873.

When we contemplate ruins, we contemplate our own future. To statesmen, ruins predict the fall of Empires, and to philosophers the futility of mortal mans aspirations. To a poet, the decay of a monument represents the dissolution of the individual ego in the flow of Time; to a painter or architect, the fragments of a stupendous antiquity call into question the purpose of their art. Why struggle with a brush or chisel to create the beauty of wholeness when far greater works have been destroyed by Time?

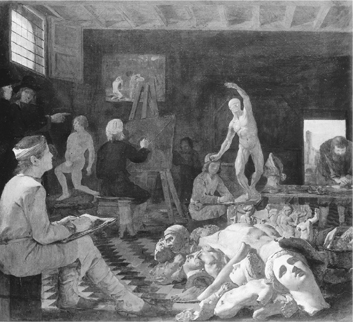

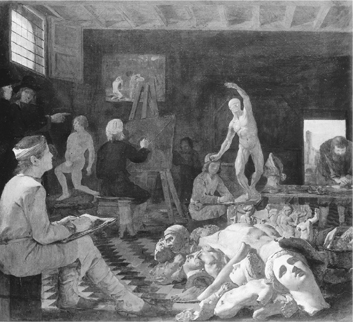

Some years ago I was walking through the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, past Rembrandts Nightwatch and into the rooms of hunters, skaters and merry peasants painted during the Golden Age of the Netherlands. I was brought up short by a small, dark painting which hung ignored by the crowds: a view of the interior of an artists studio painted in the middle of the seventeenth century by a man named Michiel Sweerts. The background of the scene was absolutely predictable: in the convention of artists academies, students were drawing an antique sculpture of a naked figure, while an older artist was casting a figure in bronze.

In the foreground, however, fragments of ancient statues of gods and heroes formed a gleaming pile of marble rubble, painted with such a heightened degree of illumination and clarity that they seemed to be a collage of photographs cut out and pasted on to the canvas. I was mesmerised by this picture, as unsettled as if I had rediscovered a forgotten nightmare. My mind travelled on to the fragmentary figures in de Chiricos surrealist paintings, and to the pallid flesh of more recent butcheries. On the left of the pile, I now noticed, was the head of a man wearing a turban, as artists did in their studios. Was this a self-portrait of Sweerts? I had never heard of him, a painter who was born in Brussels in 1618 and who died in Goa at the age of forty. Did he kill himself, for a kind of suicide is implied by the painting? There was no more information on the label but I was convinced that, at the very least, he abandoned his career as a painter. The clash of creativity and destruction in this canvas expressed the inner doubts of an artist confronted by the stupendous classical past but, ironically, the promise of ruin has been one of the greatest inspirations to western art.

The Artists Studio by Michiel Sweerts, c.1640.

When I turned away from Sweertss studio, I felt oddly dislocated but also very calm. Why, I wondered, does immersion in ruins instill such a lofty, even ecstatic, drowsiness? Samuel Johnson spoke of how Whatever withdraws us from the power of our senses whatever makes the past, the distant, or the future, predominate over the present, advances us in the dignity of human beings.That man is little to be envied, whose patriotism would not gain force upon the plains of Marathon, or whose enthusiasm would not grow warmer among the ruins of Rome. Sweerts had been to Rome, I was sure. For it is the shadow of classical antiquity which is the deepest source for the fascination with ruins in the western world. Every new empire has claimed to be the heir of Rome, but if such a colossus as Rome can crumble its ruins ask why not London or New York? Furthermore, the magnitude of its ruins overturned visitors assumptions about the inevitability of human progress over Time. London in Queen Victorias reign was the first European city to exceed ancient Rome in population and in geographical extent; until the Crystal Palace was erected in Hyde Park in 1851, the Colosseum (or Coliseum) remained the largest architectural volume in existence. Any visitor to Rome in the fifteen centuries after its sack by the Goths in AD 410 would have experienced that strange sense of displacement which occurs when we find that, living, we cannot fill the footprints of the dead.

![Woodward - State of Denial: Bush at War: [Part III]](/uploads/posts/book/211038/thumbs/woodward-state-of-denial-bush-at-war-part-iii.jpg)