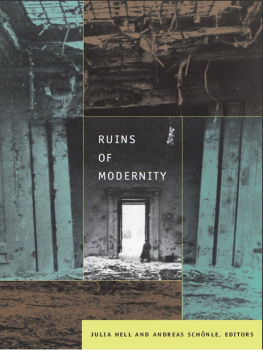

RUINS AND FRAGMENTS

RUINS

AND

FRAGMENTS

TALES OF LOSS AND REDISCOVERY

ROBERT HARBISON

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2015

Copyright Robert Harbison 2015

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780234762

Contents

In memory of happy times at

Hill Top on the North York Moors

Prologue

WHAT IS IT IN THE AIR of the present that makes us suspicious of works or histories that are too smooth, too continuous? That makes us feel fragmentariness has a kind of meaning in itself before theres any content to fill it? Is it that urban experience is inherently discontinuous and fragmented, or that the only truths we can believe are partial ones? Certainly much interesting work of the last century makes us feel that weve got part of something, not the whole Carlo Scarpa finding a ruin in a seemingly complete building at Castelvecchio in Verona, inventing an archaeological dig where no one had seen any fracture before, or Ezra Pound discovering a discontinuous ruin in Eliots lengthier draft of his Waste Land, removing sections and shortening others to leave it resembling an incomplete inscription, remnant of something once longer and more intelligible.

The story begins with dramatically shorn off ancient fragments, of the Pergamon frieze and Aeschylus plays, but we find them stuck to other things that in one sense have nothing to do with them, a grimy location in England or a rubbish dump in Egypt, but their later history is now part of them and makes these ragged scraps more riveting than the others who stayed behind in their proper places. Likewise we wouldnt trade Wang Bings ruined Chinese factories for all the wealth of Shanghai, or the ruined lives in Douglass Newcraighall or Agees Alabama for more intact ones. It was intended that the first chapter should treat inadvertent fragments, the second constructed ones, but the two bounce off and rebound on each other. Deprived lives can be ruinous for the writers who expose themselves to them.

The first chapter ends with collectors of scraps and builders from bits who salvage something from the common ruin that surrounds them, tattered Venetian brocade or marble rubble in Athens or old boards in Essex or passersby in Moscow and Kiev. The next chapter takes on the great early twentieth-century monuments to a fragmentary view: Ulysses, Battleship Potemkin, Vertovs Enthusiasm and Benjamins Arcades literature, film and literature as film in the optimistic moment when the breaking up of the old certainties and loosening of form into ceaseless movement tempted writers and filmmakers to epic scale and exuberance. There are bleaker but no less ambitious versions in Eliots and Stevenss lyric epics which predict apocalyptic collapse or Buddhist withdrawal as the likely terminus for the fragmented vision. Museums of the early twentieth century translate this way of seeing into another realm and construct a discontinuous history out of purchases themselves disruptive of the places they hail from, the collections finally graveyards disguised as historical sequence.

The chapter about modernist architecture and ruin begins with Le Corbusier and considers his villas of the 1920s as ruin-like in their bareness and their startling rearrangement of the conventional parts of the dwelling. Seen through the filter of modernism certain landscapes (Dungeness), prehistoric sites (Skara Brae) and Japanese works of art (Zen gardens) all have the same properties and bring together ruin and modernity. Brutalism, an offshoot of Corbusian clarity, restores the strong textures which had been banished, from which a resemblance to historical depth can arise, and new work can then share the numinous quality of ruin. Then comes actual modernist ruin at Cardross, followed by modernists coming to terms with war-damaged ruins, results largely unforeseen in Dllgasts Munich and Chipperfields Berlin.

Now three writers devoted to the fragment or the patchwork made of small pieces, who contrive monumental works out of scraps, seen as transcendental achievement by their readers and as failure by themselves. So Coleridge, Montaigne and Robert Burton are further ruined lives that leave behind great incomplete constructions over which their followers have climbed happily for centuries. For Coleridge ruin comes prior to achievement: he already knows he must give up before he gets the courage to begin, and his most gripping passages are fitted round the edges of other peoples pages in marginalia that scale the greatest heights disguised as commentary on someone elses text. Montaigne tried withdrawing from the world, but it did not work as expected and he was left inventing a new way of fending off melancholy by writing short pieces that followed the meanderings of his mental life. Burton too thought writing could come between him and melancholy, which partly explains how his work can be both so long and so un-unified.

The next chapter treats two unrepeatable fictions, more unlike other books than practically any known, both of which show very persuasively that confusion is a truer, deeper representation of reality than easy sense or intelligibility. In Tristram Shandy the order of the simplest events is so scrambled according to the haphazard order of subjective experience that straightening it out seems much more impossible than putting the broken pieces of a shattered pot back in order. Not that we want the ruined sequence restored; we know that would be banal and pointless.

Finnegans Wake is a far more demonic puzzle, teasing us with the idea of a narrative or narratives buried somewhere under all these layers of confusion like compost laid down by lots of intervening cultures. Like other instances scattered through this book, Joyce seems in search of a pre-literate level of consciousness more authentic than anything since language got corrupted, but the only way to get there is through a mist of words.

The last two chapters are a pair, Destruction and Reconstruction. Destruction tackles the seemingly perverse phenomenon of creating ruin deliberately, starting with Cubism, which doesnt actually destroy the canvases but the conventions of painting and the integrity of the image. Both Picasso and Braque set about making their subjects unrecognizable and in various ways unpalatable, because there is a new truth in that. Schwitters goes a step further, welcoming into the picture defaced and ruined bits of the world, scraps he picks up in the street or finds in his pockets. In the Merzbau he practises collage on an architectural scale in defiance of rational principles of building.

Gordon Matta-Clark is a pivotal figure in this book for his attacks on actual buildings, which he destroys in order to save them, or rather to find something in them of which they were unaware. He makes it possible to appreciate the radicalism of John Soane more fully than we could before Matta-Clark showed us how. Soanes attacks on structural complacency are shrouded by the fragments from his collection that pepper the walls, but they run very deep. Next come more literal and serious efforts of extermination at the hands of Byzantine, Puritan and Soviet iconoclasts, who only in the last case pay any artistic dividends. Graffiti are another pivotal phenomenon, defacement to some eyes, art to others, creating or drawing attention to urban squalor, offering a kind of critique or just doing damage. The iconoclasts wont accept that art is a protected realm no matter what it says. The issues are vaguely similar with graffiti: to welcome them you need to overlook social or ideological intents, or at least become more tolerant of them. Via Tony Harrisons poem set in a graffiti-laden graveyard we find ourselves contemplating the ultimate ruin, a corpse (or a whole lot of them), found here or on the battlefield. Deaths in the