Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Reforming the City

REFORMING THE CITY

The Contested Origins of Urban Government, 18901930

ARIANE LIAZOS

Columbia

University

Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2020 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54937-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Liazos, Ariane, 1976 author.

Title: Reforming the city : the contested origins of urban government, 18901930 / Ariane Liazos.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019015718 | ISBN 9780231191388 (hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231191395 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Municipal governmentUnited StatesHistory. | Municipal government by city managerUnited StatesHistory. | City councilsUnited StatesHistory. | City dwellersPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory. | National Municipal LeagueHistory.

Classification: LCC JS323 .L53 2019 | DDC 320.8/5097309041dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015718

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

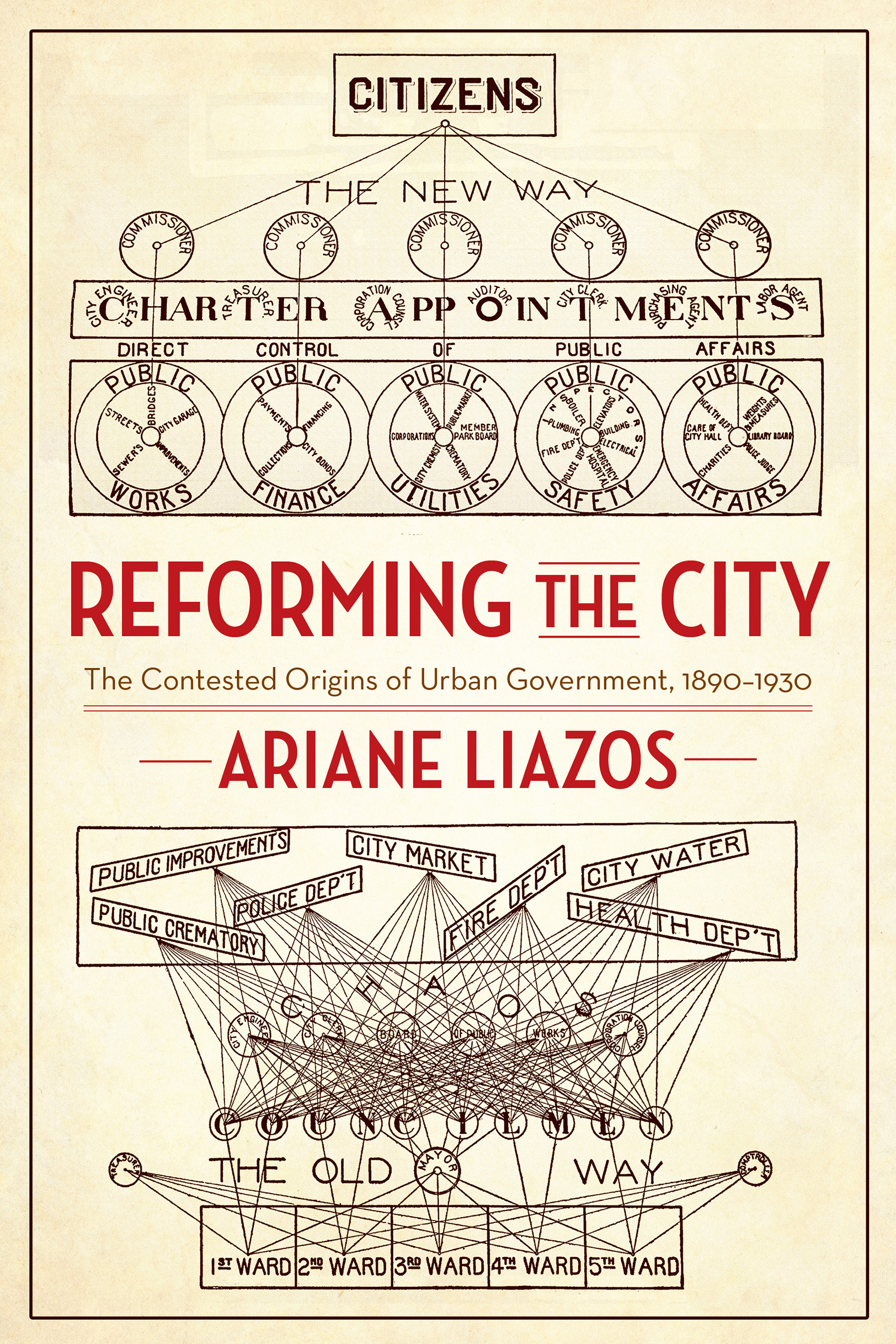

Cover art: Charles Beard, American City Government: A Survey of Newer Tendencies (New York: The Century Company, 1912)

For Marcelo, Georgia, and Aleco

Contents

W hen most Americans think of Ferguson, Missouri, they remember the events of August 9, 2014, when a white police officer fatally shot Michael Brown, an unarmed African American teenager. This incident ignited protests in Ferguson over police brutality, drew attention to the Black Lives Matter movement, and sparked national conversations about race and policing that continue to this day. Far fewer Americans, however, remember the role that the city manager and structures of Fergusons government played in creating the conditions that led to the shooting. In the aftermath of the protests, the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice undertook a detailed investigation of Fergusons government. Its report highlighted systematic racial bias in law enforcement procedures that were designed primarily to generate revenue for the city rather than to secure public safety. It also emphasized the role of the city manager and other officials in promoting these procedures. For these and other practices, the report concluded that the city violated the constitutional rights of African American residents.

Soon after the reports publication, the chief of police, a municipal judge, and the city manager resigned, but Ferguson did not change its form of government.

Despite this parallel, there are also essential differences in these two reports. In 1915, the New York Bureau of Municipal Research did not identify racism as a central concern. In fact, despite the fact that Norfolks population was over one-third African American, the report largely avoided mentioning race. One of the rare moments when it did so was telling, claiming that colored children were jailed in deplorable conditions, much worse than those of white children. While in 1915 the investigators avoided addressing institutional racism, in 2015 the Department of Justice addressed it directly and extensively.

Another key difference stemmed from the proposed solutions. While both reports recommended abolishing policing and judicial practices designed to generate revenue, the 1915 report went much further in proposing structural reforms, calling for a new charter to remake the citys organization and administration. It maintained that centralizing responsibility and authority under an individual such as a city manager would ensure a more efficient and impartial administration that would benefit the entire community.

This book tells the story of how the forms of city government that now dominate the urban landscape came to be. In doing so, it examines the silences and paradoxes of the movement that led to their creation. In roughly thirty years, city government in the United States underwent a massive transformation. An organization called the National Municipal League (NML) and reform groups across the country spearheaded campaigns to restructure the governments of American cities, and in local elections voters ratified charters that created new forms of representation and systems of administration. In 1900, the sphere of self-government in cities was circumscribed. The use of the initiative and referendum in local elections was rare, and most cities were only allowed to undertake activities expressly permitted by state laws. By the 1930s, the initiative and referendum were widespread, and roughly one-third of states had passed laws allowing home rule for cities. How were reformers able to change the governments of American cities so dramatically in only a few short decades?

Equally puzzling is the fact that many of these reforms did not achieve what their original architects intended. Initially, promoters of city manager government, shorter ballots, and nonpartisan elections claimed that these tools would increase interest in local government and make democracy workable in growing cities. In 1899, the NML issued an official program of reform focused on a variety of means to eliminate the influence of parties in local affairs. One leader of the NML summarized this program as an attempt to organize municipal government to bring about the perfection of democracy. Another promised that it would ensure that citizens would control public policy in cities and work out their own local destiny.

Today, political scientists continue to debate the overall impact of such changes, but there is a general consensus that many of these reforms lead to lower turnout in local elections, which in turn creates unrepresentative councils that pass policies that favor some residents over others. Removing parties from local politics, separating local from state and national elections, and delegating powers to appointed officials (such as city managers) rather than elected mayors all make citizens less likely to vote. This state of affairs is not what Childs and many others envisioned. Why were these reformers so successful in altering the structures of local government but so wrong in predicting what these changes would accomplish?

We might also ask how much it really matters that turnout is low and local councils are often unrepresentative. While scholars continue to debate this issue, the story of Ferguson offers compelling evidence that it matters hugely. Ferguson was one of the first cities to adopt a city manager form of government in Missouri, with a small, nonpartisan council chosen in local elections held apart from national ones. In 2014, the population was 67 percent African American, but the mayor, five of six council members, the city manager, and the chief of police were all white, as were fifty of fifty-three police officers.

Investigating Urban Reform: Sources, Scope, and Methods

Some of the earliest attempts to understand the motivations of these reformers argued for a near conspiracy. In the 1960s, historians claimed that there was a sharp difference between the professed ideology and actual practices of proponents of urban reform, suggesting that businessmen and professionals used seemingly democratic rhetoric to mask their real goals. For example, reformers attacked ward-based elections and party patronage as inherently corrupting, claiming that they prevented city government from representing the peoples will and providing efficient services. In reality, this view claims, elites simply wanted to eliminate the ward system because it provided a voice for the largely immigrant working class in local politics.