Preface

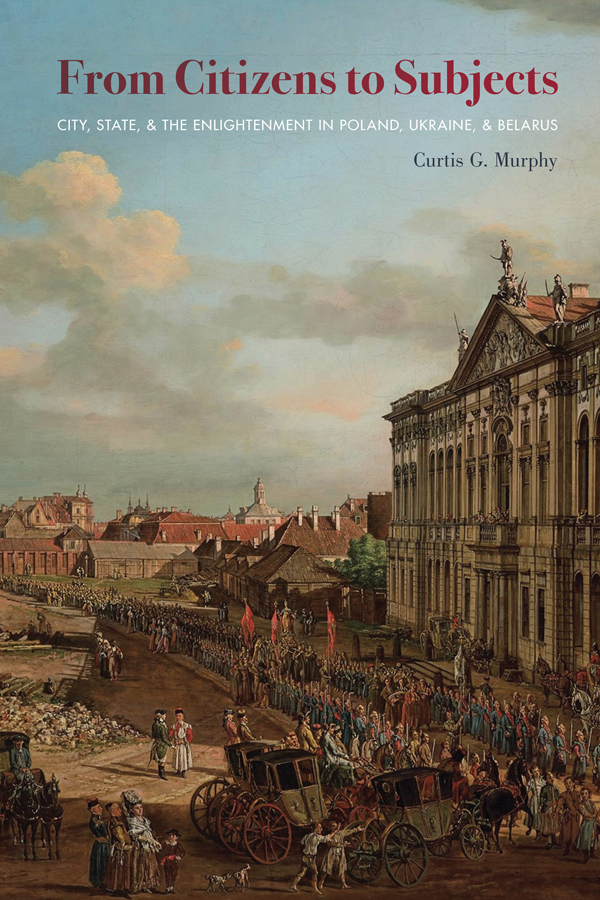

LONG AGO, IN A high school European history class in rural Tennessee, I learned that there was once a country called Poland where, because of an inconvenient voting system known as the liberum veto, nothing could be accomplished. For this reason, the states neighboring this misguided land decided to divide the territory among themselves. We never heard about this country or its people again until the subject turned to the Second World War and the Holocaust. Later, in graduate school, I discovered that this Poland was in fact the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a complex, multi-ethnic, and confessionally pluralistic polity whose peoples came under the rule of empires professing to embody progress and civilization. I came to appreciate that the broad self-governing traditions and multi-religious coexistence of the Commonwealth had much more in common with contemporary liberal-democratic rhetoric in the United States and the European Union than did the rationalistic and colonial policies of the empires that subsequently carved up this country. The fact that most Anglophone historians, even experts on what was once called Eastern Europe, have labeled the former backward and the latter progressive seemed a great injusticeas well as a lost opportunity to understand the whole picture of central and eastern Europe. Inspired by this conviction, I decided more than ten years ago to devote my graduate study to this region and to undertake the present project.

Since these initial impressions, I have become aware that many people have indeed written about the Commonwealth in English, though often indirectly in the realm of Jewish or Ukrainian studies. Moreover, a great deal of new work on the Commonwealth and its peoples has appeared in the last decade, some written by people who have become my friends and colleagues in the field; and congresses specifically devoted to Poland-Lithuania now take place with some regularity, attracting scholars not only from Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, and Russia but also from Britain, Germany, the United States, and Japan. The collapse of Communism and the expansion of the European Union have offered new opportunities to reexamine nineteenth- and twentieth-century narratives about progress and backwardness in Polish, Ukrainian, and Lithuanian historiography and have provided new perspectives to a generation of Anglophone historians for whom the division of Europe into western and eastern halves no longer forms the most salient fact of political geography.

Despite these promising developments, the territories of the former Commonwealth, like east central Europe as a whole, remain subject to orientalizing (and even auto-orientalizing) tropes and uninformed dismissals, particularly at the level of popular discourse. The tendency to conflate modern nation-states with premodern, multi-ethnic societies continues to fuel discussions about Polands history of anarchy and feudal oppression and to encourage Poles to claim the Commonwealths legacy of tolerance and participatory government as their own. At the same time, commentators unaware of premodern history frequently cite the regions lack of democratic traditions to explain contemporary political events. It is my conviction that European history in general requires a greater understanding of the territories of the former Commonwealth, not simply to correct erroneous stereotypes (often produced by imperial powers to justify their conquests) but also to reintroduce lapsed visions of liberty, self-government, and the political good. Once the rationalized unitary nation-state emerged as the only conceivable political model, alternative views of social and political organization fellinto obscurity. Nineteenth-century historians developed narratives in praise of the state-builders, wherein those monarchs like Louis XIV and Frederick the Great, who squeezed their populations in order to build palaces and wage more lethal wars, became agents of a progress, and this progress appeared to have arrived without any opportunity cost. Meanwhile, those peoples who checked regal ambitions (with the exception of the English) appeared backward and shortsighted. By overvaluing the rhetoric and perspective of the future great powers, whose dominance of Europe in prior periods was hardly foreordained, historians have omitted visions that are key to the larger picture of political change in Europe, and these neglected views may well serve as fruitful resources for contemporary political discussions. I hope that the present book may serve as a modest contribution to a larger corrective, which the history of east central Europe urgently requires.

This book would never have been conceived, must less written, without the advice, support, and constructive criticism of my dissertation advisor, Andrzej S. Kamiski, who first opened my eyeswith the help of certain voices from the past, including Jan Pasek and Bazyli Rudomiczto the fascinating and multinational world of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its many peoples. As any one of his former students would attest, Andrzej has been an extraordinary advisor and friend, supportive but (like a good guild master) unwilling to accept any trace of intellectual laziness or shoddy craftsmanship. He has been an untiring advocate for this project since its inception in 2007, the result of casual conversation over excellent wine about citizenship and the Enlightenment. Although the book has taken its own twists and turns along the way, Andrzej has never ceased to render advice, support, and criticism even after I completed my dissertation and began to pursue my career. What follows are my own ideas, as developed through an encounter with the sources and the relevant literatures, as well as conversations with many specialists in the field, but if someone should observe that I am a product of the Kamiski School, then I will consider this label a compliment of the highest order.

The research for this project took over two years, and led me to archives in Warsaw, Lublin, Krakw, and Kyiv, and I relied on several generous grants for support. The Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowship provided funds for a year of research inPoland and Ukraine, while azarski University, which was then the home of the Institute for Civic Space and Public Policy, funded eight months of research in Warsaw. I also received funding from the Georgetown History Department, where I obtained my PhD, in the form of travel grants to conduct research and non-service fellowships for completing the writing of the initial dissertation. In 2015, the Polish History Museum provided funds for a summer research trip to Warsaw in order to collect materials that I had been unable to obtain for my dissertation. Finally, a Social Policy Grant from Nazarbayev University in Astana, Kazakhstan, my new academic home, has enabled me to cover part of the costs involved in the production of this book.