Series title

New Russian Thought

The publication of this series was made possible with the support of the Zimin Foundation

- Maxim Trudolyubov, The Tragedy of Property

- Sergei Medvedev, The Return of the Russian Leviathan

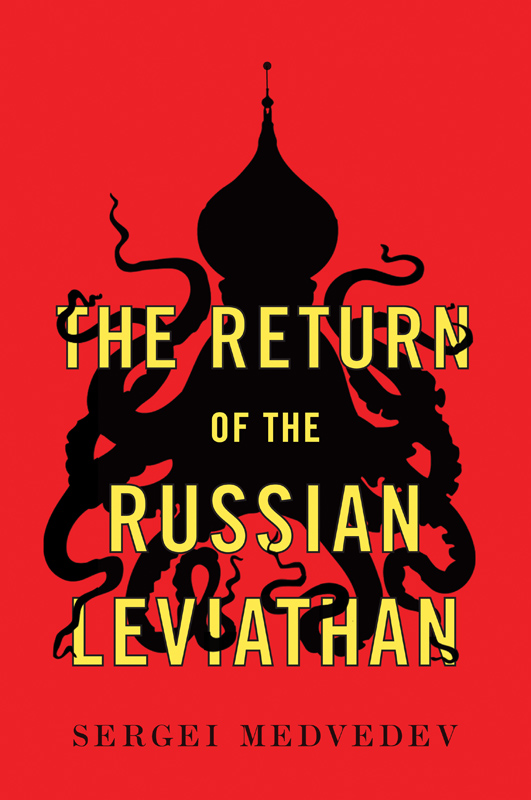

The Return of the Russian Leviathan

Sergei Medvedev

Translated by Stephen Dalziel

polity

Copyright page

First published in Russian as . Copyright Bookmate 2017

This English edition Polity Press 2020

The translation of this work was funded by the Zimin Foundation.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3604-7

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3605-4 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Medvedev, Sergei, author.

Title: The return of the Russian leviathan / Sergei Medvedev.

Other titles: Park Krymskogo perioda. English

Description: English edition. | Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA : Polity Press, [2019] | Translation of: Park Krymskogo perioda : khroniki tretego sroka. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: In this lively and well-informed book, the Russian sociologist and political scientist Sergei Medvedev sets out to explain Russias apparent relapse into aggressive imperialism and militarism during Putins third term in office, from 2012 to 2018-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019017512 (print) | LCCN 2019980220 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509536047 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509536054 (paperback) | ISBN 9781509536061 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Russia (Federation)--Politics and government--1991- | Russia (Federation)--Social conditions--1991- | Russia (Federation)--Civilization--21st century. | Russia (Federation)--Intellectual life--21st century. | Russia (Federation)--Social life and customs.

Classification: LCC DK510.763 .M4213 2019 (print) | LCC DK510.763 (ebook) | DDC 947.086/4--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019017512

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019980220

Typeset in 10.5 on 12pt Sabon

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk, NR21 8NL

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Limited

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION

On 23 February 2014, President Vladimir Putin stood on the podium of the Fisht Olympic Stadium in Sochi and presided over the closing ceremony of the Winter Olympic Games. For the first time in many years, Russia had won, coming top of the unofficial medal table. The world had yet to learn of the doping scam that was behind the triumph in Sochi; at that moment it was Putins personal victory. He had shown the world the Russia that he had built, with its pretence at global leadership, its vertical of power, its skyscrapers in the Moscow City business area, its victories on both the sporting and the gas fronts, and its fabulously expensive Winter Olympiad, which had been put on in a subtropical region.

That very same morning, 23 February, the decision was taken in the Kremlin to annex Crimea from Ukraine. Russian special forces, spetsnaz, wearing unmarked uniforms, began to land in Crimea and seize strategic points. They were referred to as little green men. Within a month, on 17 March, Crimea declared its independence, and the next day it was incorporated into Russia. Russia fell into a spectacular downward spiral from its Olympic heights. It went from being a triumphant country and member of the G8, to being an outcast, a country that flew in the face of international law and the world order, one by one ripping out the threads that had tied it to the outside world, destroying all the structures of normality and globalization which Russia had built up in the quarter of a century since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Today, almost five years later, there is no end in sight to this freefall. On 18 March 2018, on the fourth anniversary of the annexation of Crimea, Vladimir Putin was re-elected president by an overwhelming majority of the population for a further six-year term up to 2024. He has built his rhetoric on nationalism, militarism and an aggressive confrontation with the West. Russia has become a rogue state, constantly raising the stakes in its symbolic confrontation with the West, and turning its own population into the hostages of its geopolitical ambitions. But the start of this deadly spiral was laid down on that day in February 2014 with the decision to annex Crimea. Now we are all living in a post-Crimea world.

When I say we, I include also the readers of the English-language edition of this book. The toxicity of this new Russian regime instantly crossed the borders of Russia and Ukraine. As early as 17 July 2014, during a military operation started by pro-Russian separatists in the east of Ukraine, a Malaysian Airlines Boeing aircraft, flight MH17, was shot down by a BUK air defence system brought in from Russia. All 298 passengers and crew, from ten different countries, perished. Then we had the interference by Russian hackers in elections in the USA and Europe; an attempt to bring about a coup dtat in Montenegro; intervention in the civil war in Syria and the barbaric bombardment of Aleppo and other towns, with subsequent huge loss of life. Next, in March 2018 in the English city of Salisbury, there was the poisoning and attempted murder of the former Russian spy, Sergei Skripal, and his daughter, Julia, using a nerve agent. You couldnt find a better (or perhaps that should be a worse) metaphor for the toxicity of the Russian regime.

This book is an attempt to understand where this regime appeared from and how it got a grip on power. Is it simply a logical continuation of the post-Soviet transition; or is it a sharp break with the script, thanks to the will of one man? Is it a deeply Russian invention; or is it the Russian version of a global trend towards de-globalization and a return to the idea of the nation-state, with its old grievances and unfulfilled ambitions, part of which was the Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump as President of the USA?

Undoubtedly, Vladimir Putin has become the harbinger and the personification of the global return of the state. But on top of this he turned to the Russian tradition of autocracy, which goes back some 600 years, to the time when the state of Muscovy was established as the successor to the Golden Horde. As a historian, this has been fascinating to observe. I have watched as the traditional forms of power and slavery have returned; totalitarian discourses combined with Soviet figures of speech; the practice of state distribution and the rituals of class in society; and all of this linking together the Brezhnev period, Stalinism, serfdom, and practices from the time of Ivan the Terrible. The whole history of Russia is being played out before us once again, repeating most of the social, political and economic matrices that we have known; and it seems as if Russia is once again sliding back into its old historic rut.

Next page