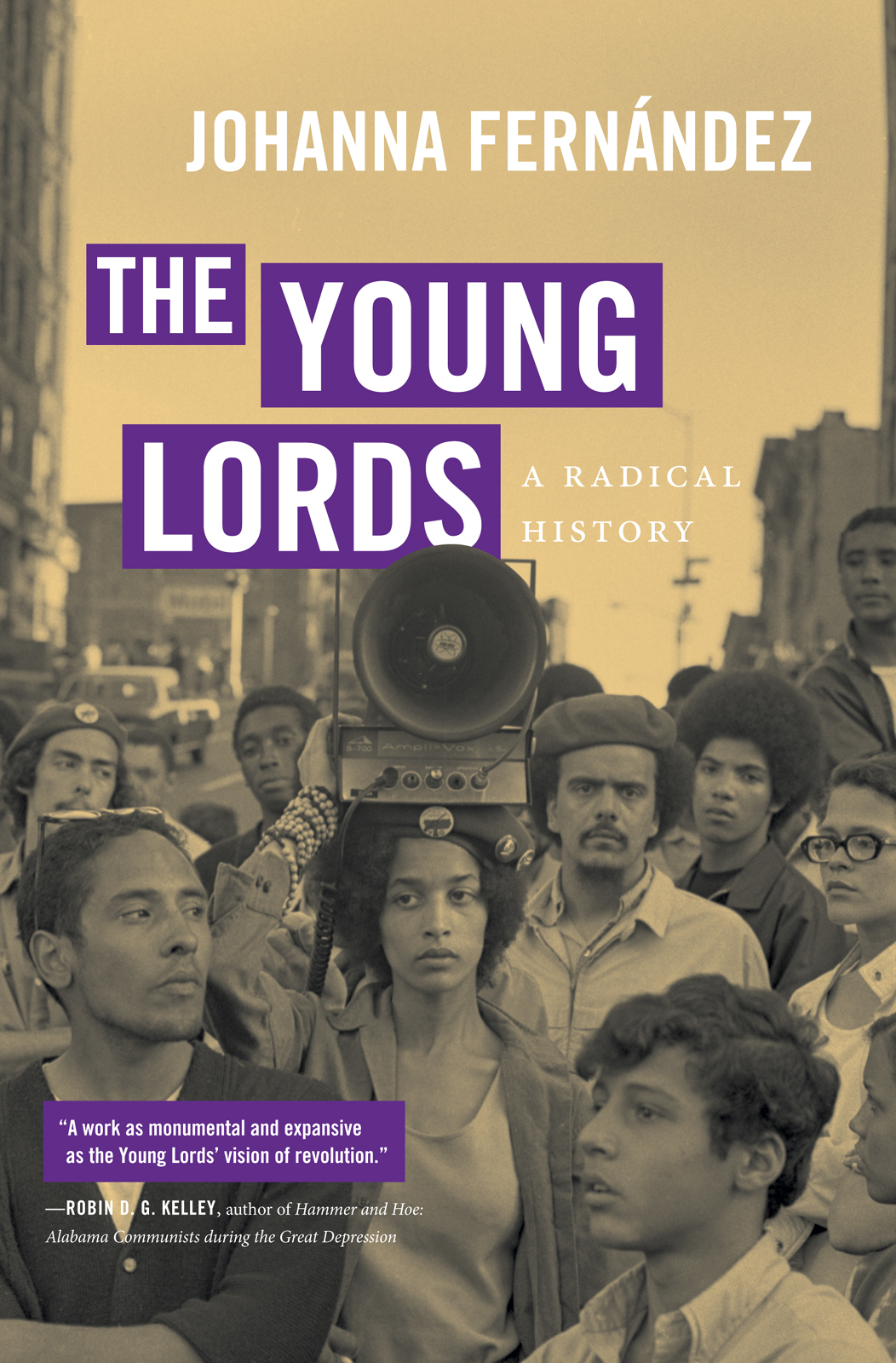

THE YOUNG LORDS

A RADICAL HISTORY

JOHANNA FERNNDEZ

The University of North Carolina Press CHAPEL HILL

This book was published with the assistance of the Authors Fund of the

University of North Carolina Press.

2020 Johanna Fernndez

All rights reserved

Designed and set in Arno and Trade Gothic types by Rebecca Evans

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the

Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Jacket photograph: Young Lords Rally, Newark, NJ, June 20, 1970; David Fenton.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fernndez, Johanna, 1970 author.

Title: The Young Lords : a radical history / Johanna Fernndez.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2020] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019037862 | ISBN 9781469653440 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469653457 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Young Lords (Organization)History. | Puerto RicansNew York (State)New YorkPolitics and government20th century. | Community activistsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | Political activistsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | Puerto RicansCivil rightsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | Civil rights movementsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | Puerto RicansNew York (State)New YorkSocial conditions20th century. | New York (N.Y.)Ethnic relationsHistory20th century. | New York (N.Y.)Social conditions20th century. | United StatesRelationsPuerto RicoPublic opinion. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century

Classification: LCC F128.9.P85 F47 2020 | DDC 323.1168/729507470904dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019037862

FOR MY BROTHERS, OSVALDO, GEOVANNY, AND TIRSO JR.,

BECAUSE WE FILLED THAT UNFORGIVING MINUTE

WITH SIXTY SECONDS WORTH OF DISTANCE RUN.

AND FOR YOU, TIRSO APOLINAR FERNNDEZ, MY FATHER.

YOU MANIFESTED THE KINDEST, FIERCEST,

AND MOST PRINCIPLED HUMANITY.

CONTENTS

FIGURES

THE YOUNG LORDS

INTRODUCTION

In the final days of 1969, the Young Lords were on top of the world. As the decade entered its midnight hour, this group of poor and working-class Puerto Rican radicals brought an alternative vision of society to life in their own neighborhood. Their aim was to reclaim the dignity of the racially oppressed and elevate basic human needsfood, clothing, housing, health, work, and communityover the pursuit of profit. In the course of a fight with East Harlems First Spanish United Methodist Church (FSUMC), they found an unlikely but irresistible setting for the public presentation of their revolutionary project.

The Young Lords had simply been looking for a space to feed breakfast to poor children before school. The church seemed an ideal place. It was conveniently situated in the center of East Harlem and housed in a beautiful, spacious building that was closed all week except for a couple of hours on Sunday. But its priest, an exile of Castros revolutionary Cuba, denied the use of its building. In response, the Young Lords charged that the churchs benign indifference to the social and economic suffering of the people of East Harlemone of the poorest districts in the citymirrored government indifference and enabled social violence. They argued further that the churchs professed goals of service to mankind and promises of happiness and freedom from earthly worries in the hereafter cloaked a broader project of social control.

Two months after their initial request was denied, the militant activists nailed the doors of the FSUMC shut after Sunday service and barricaded themselves inside. In that moment, their neighborhood deployment of the building takeovera strategy popularized by sixties radicals in universitiesgave concrete expression to growing calls for community control of local institutions in poor urban neighborhoods.

In their determination to stoke revolution among Puerto Ricans and other poor communities of color, these radicals transformed the occupied building into a staging ground for their vision of a just society. Rechristened the Peoples Church by the Young Lords, the liberated space was offered up as a sanctuary for East Harlems poor. Before long, community residents poured into the church in search of solutions to all manner of grievances, from housing evictions to the absence of English translation at parent-teacher meetings. The Lords served hot meals to school-aged children, helping to institutionalize what is now a federal program that serves school breakfast to children, and ran a free medical clinic for members of the community. They sponsored a vigorous political education program for anyone who was interested, where they taught classes in Puerto Rican and black American history, the history of the national independence movement of Puerto Rico, and current eventsan alternative to public school curricula that failed to make sense of the troubles of the poor and the brown in New York City. In the evenings, the Lords hosted festivals of the oppressed where they curated spurned elements of Puerto Rican culture and music, performed by underground poets, musicians, artists, and writersan antidote to the erasure of Puerto Rican culture and history that accompanied the U.S. colonial project that began in Puerto Rico in 1898. New genres of cultural expression were cultivated at the liberated church, among them the spoken word poetry jam, which would in the coming years become a springboard for the development of hip-hop. In the process, the Young Lords created a counternarrative to postwar media representations of Puerto Ricans as junkies, knife-wielding thugs, and welfare dependents that replaced traditional stereotypes with powerful images of eloquent, strategic, and candid Puerto Rican resistance.

At a moment of growing state violence against activists, the decision of these radicals to turn the Lords house into a site of protest was a brilliant tactical move that created a strategic sanctuary from the possibility of violent reprisals. Approximately one year earlier, in April 1968, after hundreds of Columbia University students occupied major campus buildings in protest of the Vietnam War and the universitys gentrification of Harlem, students were dragged out of the occupied buildings by police with billy clubs. At the church in East Harlem, such violence was politically untenable.

Immediately, local grandmothers began delivering pots of food to the Puerto Rican radicals through church windows, while a phalanx of National Lawyers Guild attorneys, on-site and in the churchs periphery, filed court injunctions and reminded judges and police of the barricaded radicals constitutionally protected right to protest. Teetering between sacrilege and righteousness, the Young Lords unfolding drama was captured by TV cameras parked in and outside the house of worship.

As the Young Lords fortified their programs at the church, hundreds of supporters and engrossed spectators gathered to hear about new developments during their daily press conferences. Speaking through a bullhorn out of a church window to attentive journalists outside, Young Lord Iris Benitez explained, The people of El Barrio have gotten to the point that they dont ask the why of things anymore, they just see things as they exist and try to survive. The Young Lords know the why and were trying to relay that information to the people. Born in the wake of one of the deepest political radicalizations of the century, the Young Lords creative militancy, critique of social problems spoken in the language of their peers, and socialist vision for America embodied the best of sixties radicalism.