Contents

Guide

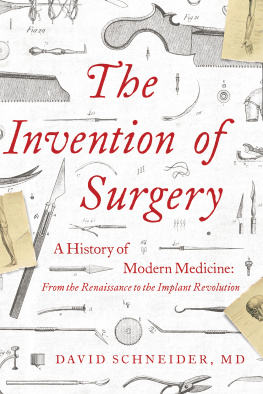

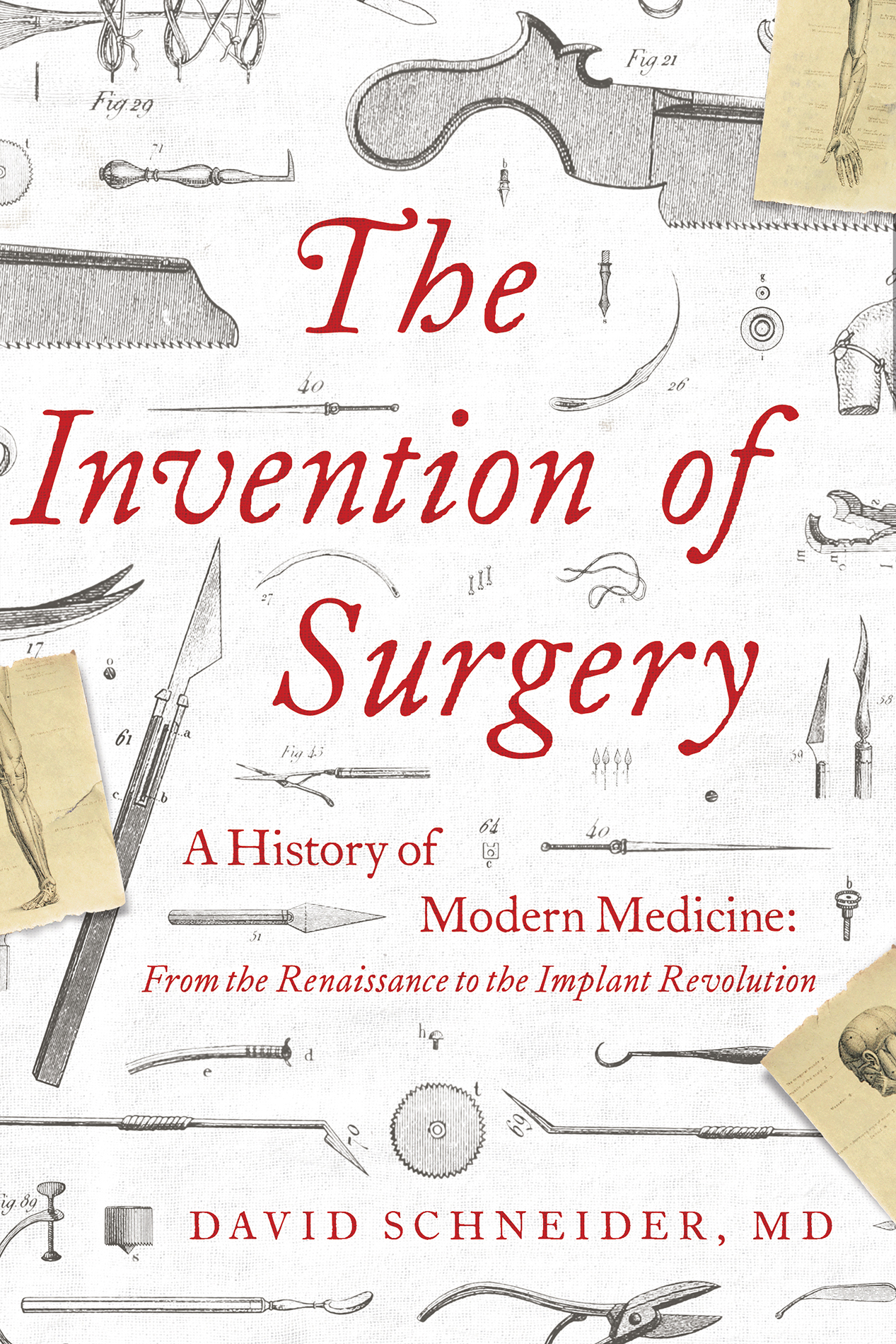

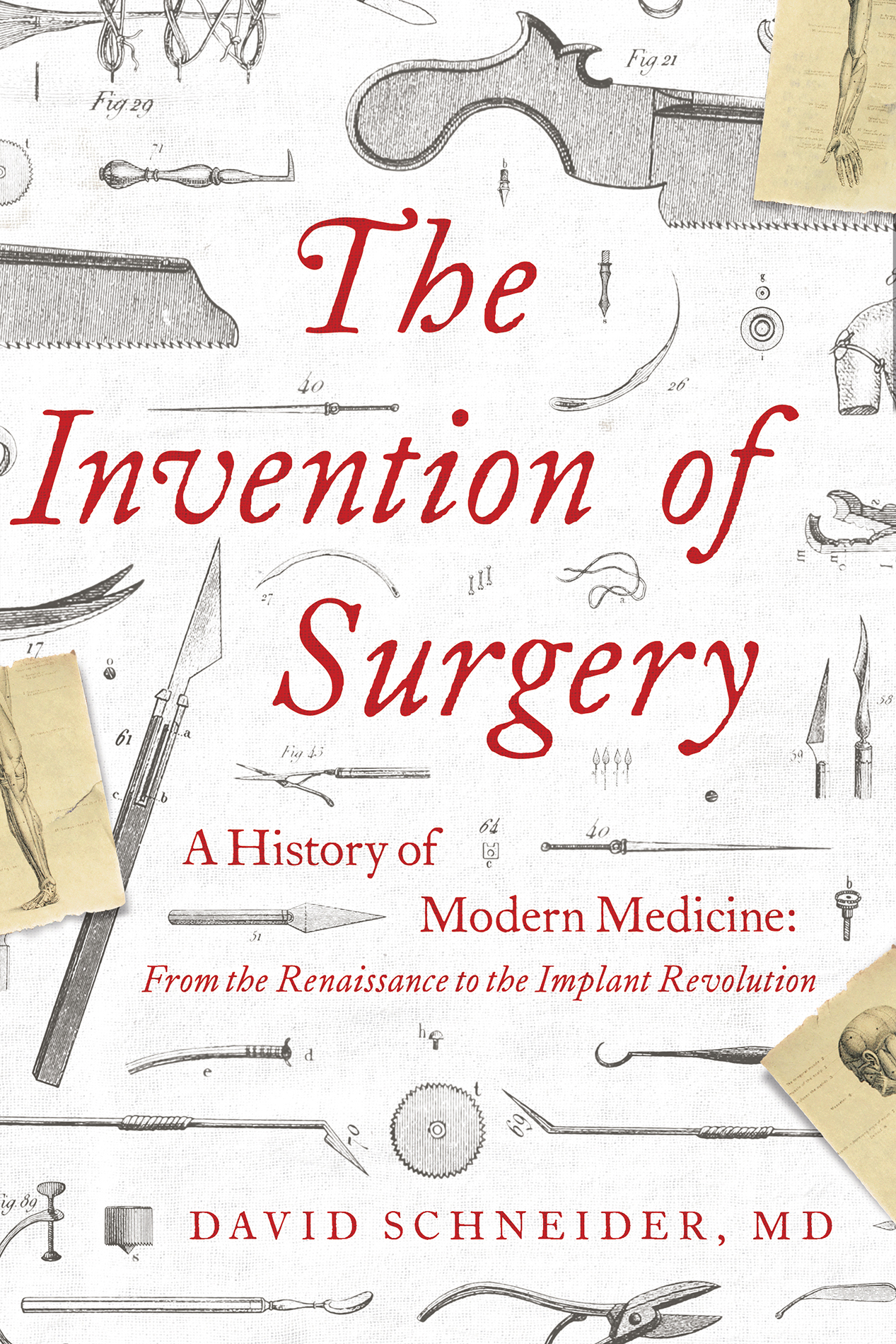

The

Invention

of Surgery

A History of Modern Medicine:

From the Renaissance to

the Implant Revolution

DAVID SCHNEIDER, MD

THE INVENTION OF SURGERY

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2020 David Schneider, MD.

First Pegasus Books cloth edition March 2020

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-316-4

ISBN: 978-1-64313-389-8 (eBook)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

For my father, J. E. Schneider, DVM

19322007

Dr. Schneider, this is Karen Lambert and Im calling from Belize. You fixed my shoulder a few years ago and Im dealing with an awful emergency. The phone line crackled and gapped, credibly confirming the Central American origin. My husband and I are on an eco-tour vacation, and two days ago at a zip line park, his harness broke and he fell twenty feet. His elbow dislocated and broken bones were sticking out of his arm.

Karen went on to explain that her husband, Mark, had been shuttled to a small hospital in a nearby town, but that she had not been allowed to see him since he was admitted forty-eight hours before. The local doctor had reduced the elbow (aligning the joint and broken bones) but had not operated. Frantic, she pleaded for help to extricate her husband from the unsophisticated infirmary and convey him to the United States.

My team and I sprang into action, and working with a local air ambulance company, facilitated transport to Denver the next day on a private jet staffed with nurses. An ambulance met them at Denver International Airport, and after rushing him to my level one trauma center, we prepared for emergency surgery at 2:00 A.M.

All day long I had prepared for the worst. I was worried about a life-threatening infection, and knew for certain that loss of his arm was a distinct possibility. At best, I was hoping that we could minimize lifelong disability and hope for reasonable function. When I met with Mark and Karen in the pre-op holding area, they looked understandably exhausted and emotionally empty. Mark was lying on a gurney in a white surgery smock; Karen was still wearing the logoed travel company T-shirt, khaki shorts, and adventure sandals. Just as I was about to give them the big talk about doing our best to save his arm, Mark looked up at me with travel-weary eyes and informed me:

I want to be able to play softball this summer and I dont want scars.

Stunned, I tried recalibrating, sensing the need to educate Mark about the grave consequences he was facing. I couldnt break through. He equated Karens successful shoulder reconstruction and stabilization to his present situation. I mentioned the 80 percent death rate associated with open fractures just one hundred years ago, and tried to convey the complex nature of the ligaments, tendons, and muscles that held his elbow together, and the challenge of closing gnarly traumatic lacerations, but to no avail. Although I liked Marks optimism, I was concerned he wasnt grasping the potential for serious complications, and the certainty that his arm would never be the same.

By dint of miracle, his surgery went extremely well. He didnt die, he didnt lose his arm, and he (somehow) ended up with superb function and had no disability. In fact, his scars were unnoticeable.

At his final appointment (following a softball game), we recalled his travails and assessed his final outcome. I tried one last time to discuss how close he came to losing his arm and how just a short time ago he would have almost certainly perished from this injury. Mark is an aerospace engineer, so common here in Boulder, Colorado, and despite his great intelligence, has no perspective about modern surgery. In fact, almost no one does, including surgeons. So when I reviewed his progress and compared it to how it would have gone just seventy-five years ago, Mark was shocked that there was no such thing as plates and screws, or even antibiotics, in the years before World War II.

Not that long ago, no one believed in germs. Although the first anesthetic drugs were discovered in the mid19th century, surgery was still extremely dangerous until a small group of physicians and scientists were able to prove that the minuscule organisms that invisibly inhabit our world are the cause of infections. This knowledge triggered a revolution in medicine and surgery, and the first triumph was convincing surgeons to wash their hands before surgery.

An agonizing interval of seventy years passed from the acceptance of the germ theory to the development of antibiotics. During that period, surgery slowly developed, but to our modern eyes was highly limited in scope and efficacy. But a simultaneous series of inventions, like the development of polymers and transistors, modern alloys and antibiotics, and the undergirding establishment of private health insurance and Medicare, made modern surgery what it is.

Implant surgery, such as joint replacement, cardiac stent placement, lens surgery, and neurosurgical shunts, only became possible about fifty years ago. Implants, now numbering in the millions per year worldwide, were unthinkable a century ago, but this modern marriage of science, art, hubris, imagination, madness, bravery, and patience is nothing short of an implant revolution .

There are many encyclopedias of surgery and compendia of surgeons biographies. There are a few books written in recent decades that truly bring to life some of the renegades and pioneers who helped make our world modern. What is missing is a narrative that interconnects those lives, weaves together their tales, and explains how we got to now.

In this book, therefore, I set out to tell the story about the invention of surgery. In modern historiography, it has become au courant to presuppose that there are really no lone geniuses and almost no eureka moments. That is simply not true in the topic of surgery. There are many virtuosi who saw further in their underrated genius, challenged the status quo, and improved the lot of mankind more than in any other field. Here are their stories.

Life is short, and Art long; the crisis fleeting; experience perilous, and decision difficult. The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and externals cooperate.

Hippocrates, Aphorisms , Section 1

The fact is that he whose purpose is to know anything better than the multitude do must far surpass all others both as regards his nature and his early training.

Galen, On the Natural Faculties

As the junior resident on the hand surgery service, I spend more time tending to the patients on the hospital floor and in the emergency room, and less time in the operating room. This summer has been hectic, with multiple replants (the reattachment of fingers after trauma suffered at factories, lumber mills, and backyard fireworks mishaps). Patients get airlifted or ambulanced to our trauma center from all over our region in hopes of saving their hands.