Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Patricia

1 Gerard David: the flaying of Sisamnes from The Judgement of Cambyses, 1498, oil on wood.

(Public domain; source: Wikimedia Commons)

2 Tycho Brahe (line engraving by J. L. Appold after J. de Gheyn, 1586).

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

3 Leonardo Fioravanti, 1582.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

4 An eighteenth-century depiction of an agricultural graft, 1772.

(Wellcome Collection: Public Domain Mark 1.0)

5 A dissection in progress: the anatomy professor at his lectern, 1493.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

6 Bloodletting, sixteenth century.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

7 Andreas Vesalius dissecting a female cadaver, 1555.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

8 Male corch, 1556.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

912 Gaspare Tagliacozzis skin graft, from De Curtorum Chirurgia.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

13 A Perfect Nose, from De Curtorum Chirurgia.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

14 William Harveys experiments on the valves, De Motu Cordis, 1628.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

15 Richard Lowers transfusion equipment, 1666.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

16 A transfusion between animals and humans, 1667.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

17 Transfusion of lambs blood to human, 1705.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

18 Italian blood transfusion, 1668.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

19 The Country Tooth-Drawer, after Richard Dighton.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

20 Imaginary rendering of Vaucansons digesting duck, 1899.

(Scientific American: public domain)

21 Vaucansons loom.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

22 Engraving of Trembleys polyps, 1744.

(Wellcome Collection: Public Domain Mark 1.0)

23 Attempt to resuscitate a drowned woman by blowing into her anus, 1774.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

24 Resuscitation set, Europe, 180150.

(Science Museum, London: CC BY 4.0)

25 The Resurrection.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

26 The London Dentist.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

27 Head of a Maltese cock, Godart, Thomas.

(St Bartholomews Hospital Archives & Museum: CC BY 4.0)

28 A Caza de Dientes, Francisco Goya, 1799.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

29 Transplanting of Teeth by Thomas Rowlandson, 1787.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

30 Blundells Impellor.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

31 Blundells Gravitator, as depicted in The Lancet, 1829.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

32 Depiction of the assassination of President Sadi Carnot of France, 1894.

(Le Petit Journal: public domain)

33 Example of Marie-Anne Leroudiers work.

( Lyon, Muse des Tissus Pierre Verrier)

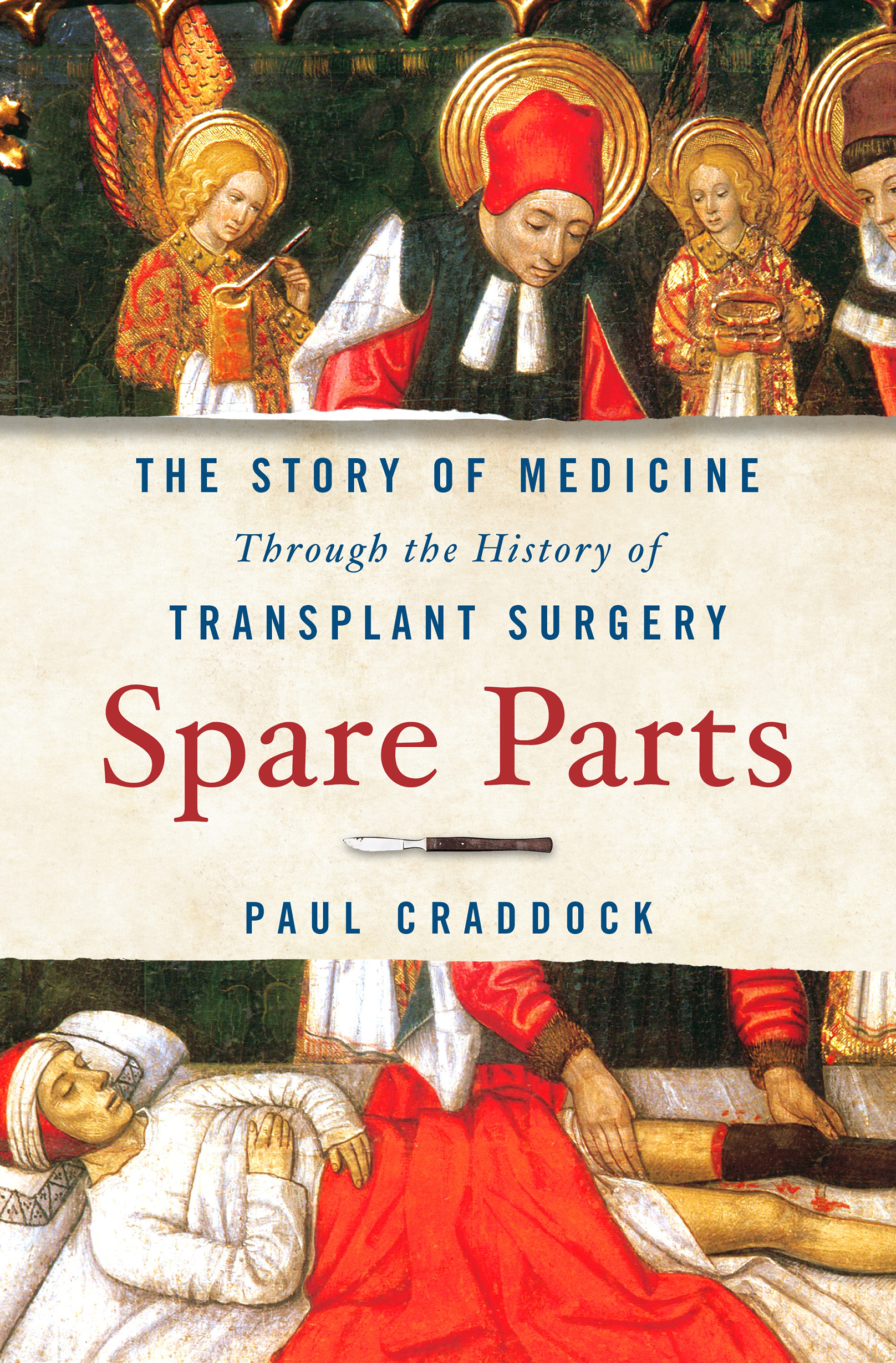

34 A Vergers Dream: SS Cosmas and Damian transplanting a leg, 1495.

(Wellcome Collection: CC BY 4.0)

35 Alexis Carrel with a black dog and a white dog, with legs transplanted.

(Novartis Pharma France)

36 Carrel and Lindbergh with their perfusion device.

(National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

37 A patient being dialysed on one of Willem Kolffs early artificial kidneys.

(Getty Images)

38 A spinach leaf seeded with heart cells.

(Worcester Polytechnic Institute, with thanks to Professor Glenn Gaudette and Dr Joshua Gershlak)

The kidney bloomed, going from a miserable grey to many shades of vital red as blood rushed through its newly connected vessels. An organ that could seconds ago have been mistaken for discarded offal was now filled with life, resurrected and visibly claimed by a new body. This was my first time watching a kidney transplant.

Id met the kind-eyed patient twenty minutes before he went under and watched as three scrubbed-up figures draped his body with green sheets. He disappeared under these by degrees like the Cheshire Cat fading into the landscape. But instead of a smile, we were left with a disembodied abdomen. As anonymous figures placed the last of the drapes, an auxiliary burst in with a trolley, pushing it up against the wall between a switched-off respirator and a rack of gleaming metal instruments. It was the donor kidney, lying on a bed of ice, monochrome and well trimmed with fat. Much like its intended recipient under the drapes, its life had been suspended. It resembled a calfs kidney past its sell-by date an impression at odds with its true value. The desperately ill Mr Bhatti had received it as a gift from his brother, who was now recovering on a ward elsewhere in the hospital.

The two surgeons and their assistants stood either side of the abdomen, absorbed in the business of making their way through layers of skin, fat and muscle. Surgeons prefer diathermy for this job nowadays, burning rather than slicing the parts asunder. There is less bleeding this way but, until they break through into the cavity, the scorched flesh fills the operating theatre with the aroma of a Sunday barbecue. Once theyd finished severing the final bits of sinew, the pace slowed as the surgical team prepared the inner landscape of the abdomen, identifying, teasing out and labelling arteries, veins and the ureter. During these hours of intense concentration, my attention was drawn to the new organ lying almost forlornly on its trolley. As time went by, blood leached out of it, its bed of ice slowly reddening.

Id half expected the insistent beep of a heart monitor and steady hiss of a respirator to fill the room with urgency, but the machines keeping Mr Bhatti alive were silent. Crocs shuffled on the polished floor as one of the surgeons made his way over to the kidney and lifted it from its bed. He brushed away the flakes of red ice with the back of a gloved finger. Holding it aloft and cupping it in his hands, he then brought it to the operating table, where four more hands were ready to receive and stitch it in. A pause. The lead surgeon invited me up to the table to peer inside the cavity, hands behind my back so I wouldnt touch anything. Amongst the red anatomy, this lifeless grey mass looked diminished, limp and out of place. Three vessels connected it to the rest of the body, with tiny clamps temporarily stopping the flows of blood and urine. Before my eyes, the surgeon removed these devices and in a matter of seconds the kidney turned from grey to pink, then almost red. It seemed as if life itself had cascaded from one mans body into anothers.

Everything about this experience suggested that transplantation was a decidedly modern concern. The theatre was crowded with complex machines, sophisticated instruments and digital displays. Chemical smells accompanied the aroma of burning human flesh. The procedure was a sterile, well-choreographed affair. But transplant surgery is far from an exclusively modern phenomenon, with a surprisingly long and rich history that stretches back as far as the Pyramids.