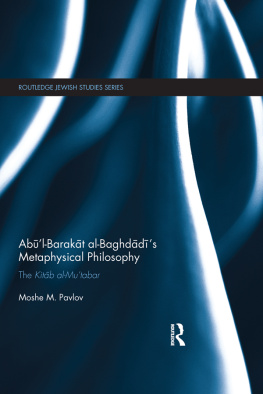

Edward Feser

Aristotles Revenge

The Metaphysical Foundations

of Physical and Biological Science

Bibliographic information published by Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de

2019 editiones scholasticae

53819 Neunkirchen-Seelscheid GERMANY

www.editiones-scholasticae.de

ISBN 978-3-86838-199-3

2019

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use of the purchaser of the work.

eBook-Conversion: CPI books GmbH, Leck, Germany

Contents

0. Preface

The central argument of this book is that Aristotelian metaphysics is not only compatible with modern science, but is implicitly presupposed by modern science. Many readers will be relieved to hear some immediate clarifications and qualifications. First, I am not talking about Aristotles ideas in physics, as that discipline is understood today. For example, I am not going to be defending the claim that the sublunary and superlunary realms are governed by different laws, or the doctrine of natural place. I am talking about the philosophical ideas that can be disentangled from this outdated scientific framework, such as the theory of actuality and potentiality and the doctrine of the four causes. These are, again, metaphysical ideas rather than scientific ones. Or to be more precise, they are ideas in the philosophy of nature, which I regard as a sub-discipline within metaphysics, for reasons I will explain in chapter 1.

Second, I am not arguing that working scientists in general explicitly employ or ought to employ these philosophical ideas in their everyday research. I am arguing that the practice of science, and the results of science at least in their broad outlines, implicitly presuppose the truth of these ideas, even if for most practical purposes the scientist can in his ordinary work bracket them off. I am primarily addressing the question of how to interpret the practice and results of science, not the question of how to carry out that practice or generate those results.

Third, even then my remarks about those results will be very general. To be sure, I will have a lot to say about why relativity theory, quantum mechanics, chemistry, evolution, and neuroscience in no way undermine the central ideas of Aristotelian philosophy of nature, and even presuppose those ideas in a very general way. But there are in each case a number of different ways the Aristotelian might work out the details, and I make no pretense of having done more than scratch the surface here. An Aristotelian philosophy of physics, an Aristotelian philosophy of chemistry, an Aristotelian philosophy of biology, and an Aristotelian philosophy of neuroscience would each require a book of its own adequately to work out. If the relatively cursory treatments I provide encourage others to carry out these jobs more thoroughly, I will not be displeased.

This work is a sequel to my book Scholastic Metaphysics: A Contemporary Introduction , and builds on the main ideas and arguments developed and defended there. To be sure, this new book can be read independently of the older one, since I summarize in chapter 1 the most crucial points from the earlier book. But the skeptical reader who suspects that I have in the present work begged some question or insufficiently defended some background assumption is advised to keep in mind that he will find the full-dress defense in the earlier book.

I borrow the title Aristotles Revenge from an article by the late James Ross (1990), from whose work I have learned so much. One of Rosss key insights concerns the ways that contemporary analytic philosophers have rediscovered and vindicated Aristotelian ideas and arguments, albeit often without realizing it. Scholastic Metaphysics developed that theme at length, and this new book continues in that vein. My subtitle is an homage to E. A. Burtts classic book The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science. Burtts book is essential reading, but it raises more questions than it answers. The point of my book is to answer them.

This is the fruit of many years of work, and as always, I owe my wife and children an enormous debt of gratitude for patiently bearing with my absence through the hours I spend chained to the desk in my study. So, I give my love and thanks to Rachel, Benedict, Gemma, Kilian, Helena, John, and Gwendolyn. I also thank my publisher Rafael Hntelmann for the superhuman patience he showed in awaiting delivery of the book, which came long after the original deadline.

In the years during which I worked on this book, I lost my sister Kelly Eells to pancreatic cancer, and then my father Edward A. Feser to Alzheimers disease. I dedicate this book to their memory, and to my mother Linda Feser, whose example of self-sacrifice and dignity in the face of great suffering has been heroic and inspirational. Mom, Dad, and Kelly, I love you.

1. Two philosophies of nature

1.1 What is the philosophy of nature?

The nature of the philosophy of nature is best understood by way of contrast with natural science on the one hand and metaphysics on the other, between which the philosophy of nature stands as a middle ground field of study.

The nature of natural science is itself a topic about which I will have much to say in this book, but for present purposes we can note that the natural sciences are concerned with the study of the actually existing empirical world of material objects and processes. For example, biology investigates actually existing living things the structure and function of their various organs, the taxa into which they fall, their origins, etc. Chemistry investigates the actually existing elements and the processes by which they get organized into more complex forms of matter. Astronomy investigates the actually existing stars and their satellites and the galaxies into which these solar systems are organized. And so forth.

Metaphysics, meanwhile, investigates the most general structure of reality and the ultimate causes of things. Its domain of study is not limited merely to what happens as a matter of contingent fact to be the case, but concerns also what could have been the case, what necessarily must be the case, what cannot possibly have been the case, and what exactly it is that grounds these possibilities, necessities, and impossibilities. Nor is it confined to the material and empirical world alone, but investigates also the question whether there are or could be immaterial entities of any sort God, Platonic Forms, Cartesian res cogitans, angelic intellects, or what have you. In addition, metaphysics investigates the fundamental concepts that the natural sciences and other forms of inquiry all take for granted.

For example, whereas the natural sciences are concerned with various specific kinds of material substances stone, water, trees, fish, stars, and so on metaphysics is concerned with questions such as what it is to be a substance of any kind in the first place. (Is a substance a mere bundle of attributes, or a substratum in which attributes inhere? Are material substances the only possible sort? And so on.) Similarly, the natural sciences are concerned with various specific kinds of causal process combustion, gravitation, reproduction, and so on whereas metaphysics is concerned with questions such as what it is to be a cause in the first place. (Is causation nothing more than a regular but contingent correlation between a cause and its effect? Or does it involve some sort of power in the cause by which it necessarily generates its effect? Is there only one kind of causality? Or are there four, as Aristotle held?) Whereas the natural sciences explain the phenomena with which they are concerned by tracing them to the operation of ever deeper laws of nature, metaphysics is concerned with issues such as what it is to be a law of nature and why such laws operate. (Is a law a mere description of a regular pattern in nature? If so, how could it explain such patterns? Why is the world governed by just the laws of nature that do in fact govern it, rather than some other laws or no laws at all?)