Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

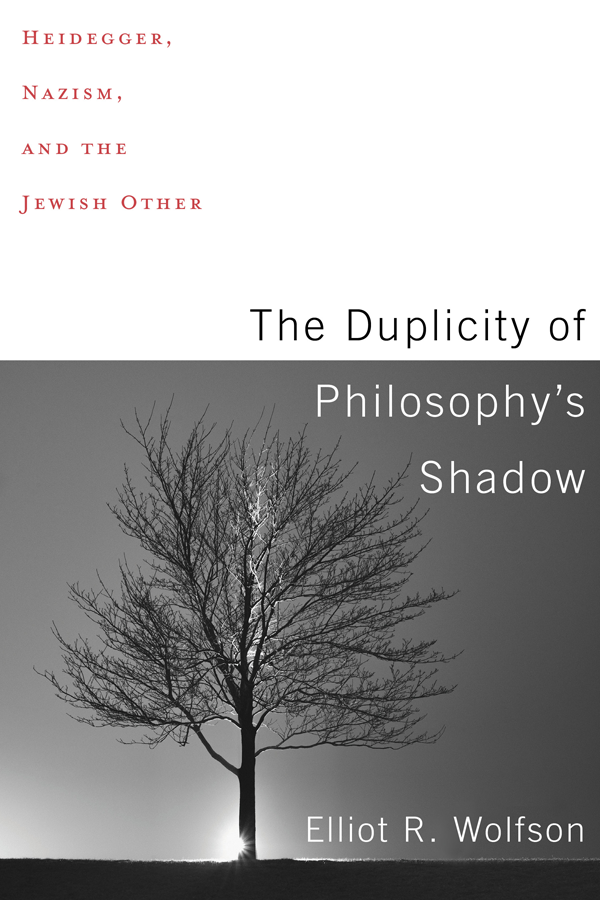

THE DUPLICITY OF PHILOSOPHYS SHADOW

The Duplicity of Philosophys Shadow

HEIDEGGER, NAZISM, AND THE JEWISH OTHER

Elliot R. Wolfson

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54624-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wolfson, Elliot R., author.

Title: The duplicity of philosophys shadow: Heidegger, Nazism, and the Jewish other / Elliot R. Wolfson.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049988 | ISBN 9780231185622 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231185639 (pbk.: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Heidegger, Martin, 1889-1976. | National socialism.

Classification: LCC B3279.H49 W627 2018 | DDC 193dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049988

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

To Aaron

For abiding when many others absconded

As every past generation has had to disenthrall itself from an inheritance of truisms and stereotypes, so in our time we must move on from the reassuring repetition of stale phrases to a new, difficult, but essential confrontation with reality. For the great enemy of the truth is very often not the liedeliberate, contrived and dishonestbut the mythpersistent, persuasive and unrealistic. Too often we hold fast to the clichs of our forebears. We subject all facts to a prefabricated set of interpretations. We enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.

John F. Kennedy, Commencement Address at Yale University, June 11, 1962

The matter of thinking is always confoundingall the more in proportion as we keep clear of prejudice. To keep clear of prejudice, we must be ready and willing to listen.

Martin Heidegger, What Is Called Thinking?

CONTENTS

into the book

whose name did it take in

before mine?

the line written into

this book about

a hope, today,

for a thinkers

(un

delayed coming)

word

in the heart

Celan, Todtnauberg

Martin Heidegger (18891976) powerfully transformed the twentieth-century philosophical landscape and exercised an inordinate influence on a wide variety of other disciplines. His personal shortcomings and lapses in ethical judgment, attested in his explicit complicity with National Socialism, are well known and cannot be easily justified or dismissed as miscalculations based on inadequate knowledge or lack of savvy. In this book I will focus on Heideggers embrace of Nazismthe so-called affaire Heidegger and its connection to some crucial aspects of his philosophical enterprise. Needless to say, the bibliography on this sensitive, and what has become sensational, topic, largely due to the publication of the Schwarze Hefte , the personal notebooks covering the years 19311948, is considerable in size and scope. There is no pretense to treat the subject comprehensively or exhaustively. My contribution will, hopefully, consist of shedding new light on the vexing labyrinth of issues by approaching it not as a member of the Heideggerian guild, as it were, or as an intellectual historian of National Socialism, anti-Semitism, or even twentieth-century philosophy, but as a scholar of Jewish mysticism, albeit one whose work has been deeply informed by the disciplines of hermeneutics and phenomenology and especially by Heidegger.

In the infamous Der Spiegel interview, Nur ein Gott kann uns noch retten, conducted in September 1966, Heidegger demonstrated that he was cognizant of what his fate would be: Probably the polemics will flare up again and again, whenever the occasion presents itself. As a framework for my investigation of what Heidegger rightly identified as a matter that is polemical to its core, I will adopt the eminently sensible sentiment expressed by Jacques Derrida on the first day of the Heidelberg conference on Heideggers philosophy and politics, which took place on February 56, 1988:

Often, when I see so many people in France suddenly interested in Heideggers Nazism, shouting loudly and accusing philosophers of having said nothing to them, and setting out to condemn not only Heidegger but also the living, I would like to ask them a very simple question: okay, lets talk; have you read Sein und Zeit ? to take only that example. Those of us who began to read this book, to confront it in a close explication, in a questioning and nonorthodox way, know well that, among others, it is still waiting to be read; that there are still, in this text of Heidegger, immense resources. Consequently, one has a right to ask those who wish to draw very rapid conclusions linking the philosophical text and a political comportment that they begin at least to try to read.

I trust the readers of this book will agree unconditionally to the condition laid down by Derrida: no thinker is above criticism, certainly not one as controversial as Heidegger, but even he, nay especially he, deserves to be read before he is castigated as an outcast and his lifework deemed irredeemable. As Derrida added, philosophers particularly are obliged to read Heideggers entire oeuvre rigorously and scrupulously so that they do not relinquish their individual political responsibility. In his comments at the colloquium Reading Heidegger held at the University of Essex in May 1986, Derrida makes clear that what is at stake is not only the fairly banal and eminently sensible plea to read Heidegger if one wants to understand his thought, but the far more provocative and unexpected assertion that to understand Nazism philosophically one must go through the questions proffered directly and indirectly by Heidegger.

Are we sure today that we can understand what Nazism was, without asking all the questions, the historical questions, Heidegger asks? I am not sure. I am not sure that we have today really understood what Nazism was. And if we have to think and think about that, I believe we will have to go through , not to stop, at Heideggers questions, go through Heideggers trajectory and his project. We cannot understand what Europe is and has been during this century, what Nazism has been without integrating what made Heideggers discourse possible. And then you will have to read Heidegger to see what has occurred.

The burden marked by Derridato wrestle with Heidegger as a way to think through to the depth of what we condemnis, I am afraid to say, one that can be borne only by those willing to invest an inordinate amount of time and energy in reading through this vastly arduous corpus.

This, it will be recalled, is also the crux of Derridas caustic reprimand of Victor Farass Heidegger et le nazisme , in the interview with Didier Eribon published in Le Nouvel Observateur , November 612, 1987: Beyond certain aspects of the documentation and some factual questions, which call for caution, discussion will focus especially on the interpretation, let us say, that relates these facts to Heideggers text, to his thinking. The reading proposed, if there is one, remains insufficient or questionable, at times so shoddy that one wonders if the investigator began to read Heidegger more than an hour ago. And only if one is committed to that effort is it possible to embark upon the mission that Derrida boldly articulates: