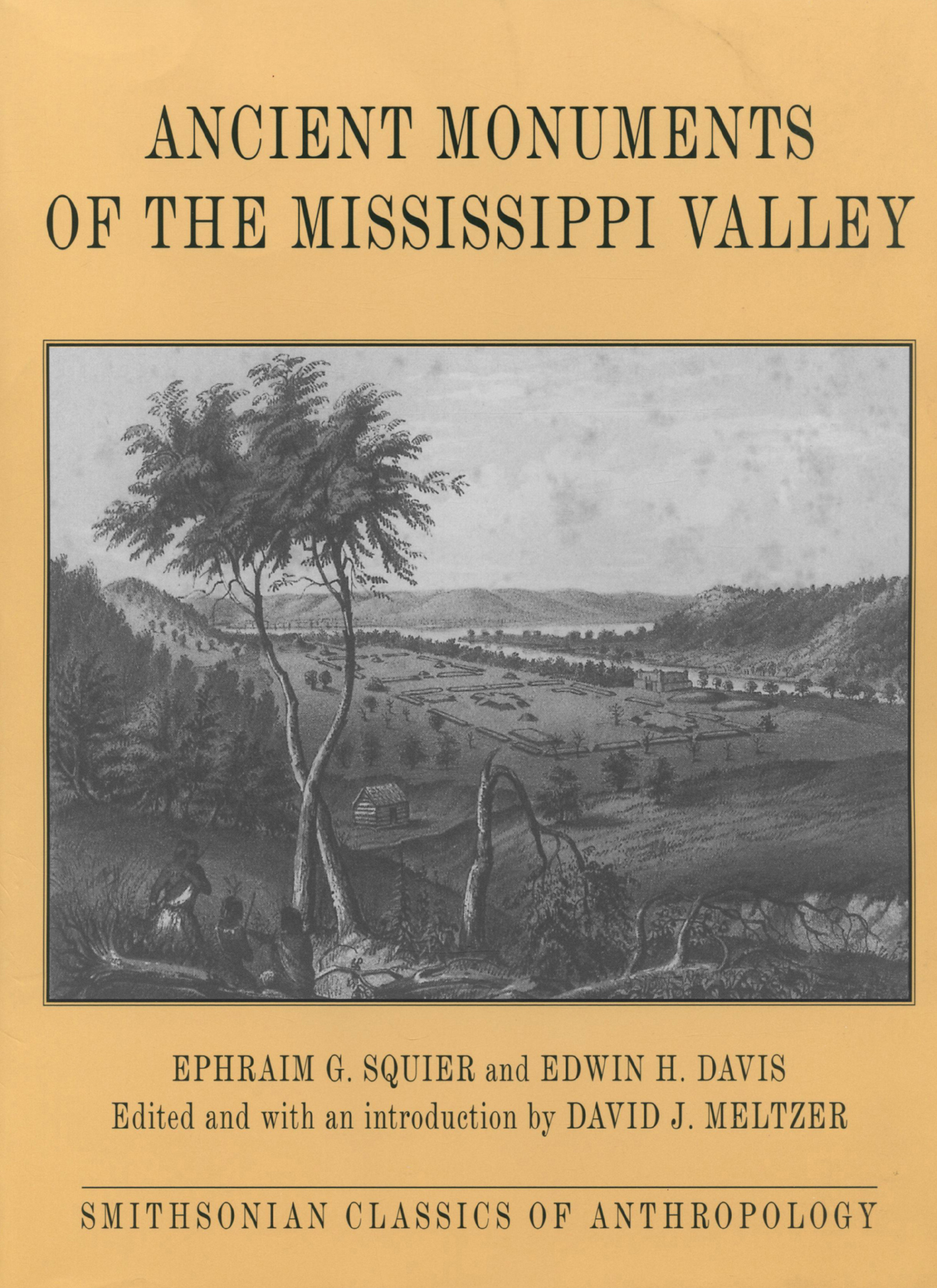

Ephraim G. Squier + Edwin H. Davis - Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley

Here you can read online Ephraim G. Squier + Edwin H. Davis - Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1998, publisher: Smithsonian Books, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley

- Author:

- Publisher:Smithsonian Books

- Genre:

- Year:1998

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Introduction 1988 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

The volume editor and Smithsonian Books are profoundly grateful to Susan and Claude C. Albritton III for their generous support of this publication, given in memory of Claude C. Albritton Jr., who so highly valued the history of science and recognized its vital importance to contemporary scholars.

New material for this edition edited by Jan McInroy

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Squier, E. G. (Ephraim George), 1821-1888.

Ancient monuments of the Mississippi Valle: comprising the results of extensive original surveys and explorations / by E. G. Squier and E. H. Davis.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-56098-873-8 (hardcover: alk. Paper)ISBN 978-1-56098-725-3

1. Indians of North AmericaMississippi ValleyAntiquities. 2. MoundsMississippi Valley. 3. Mississippi ValleyAntiquities. I. Davis, E. H. (Edwin Hamilton), 1811-1888. II. Title.

E78.M75S64 1998

976.201dc21

An e-Book reissue (ISBN 978-1-58834-523-3) of the original cloth edition.

This book may be purchased for education, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P.O Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

For permission to reproduce any of the illustrations, please correspond directly with the sources. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

www.SmithsonianBooks.com

This 150th anniversary reissue of

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley

is dedicated to the memory of

James B. Griffin, 19051997

David J. Meltzer

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, by Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis, was the first publication ever issued by the Smithsonian Institutionin any subject. As such, much was riding on it. The fledgling institutions first publication, in 1848, would send a clear signal to Congress, the scientific community (here and abroad), and especially the Smithsonians Board of Regents, all of whom were watching closely to see how Joseph Henry (the institutions first secretary) would choose to interpret James Smithsons generous but enigmatic behest that the institution he endowed have as its object the increase and diffusion of knowledge.

On Ancient Monuments Henry (17971878) staked his vision for the Smithsonians future, for that book would, inevitably, set a scholarly and scientific precedent for the institution, launch its Contributions to Knowledge series, and thus help (or hinder) his efforts to establish the Smithsonians credibility on the national and international scientific scene. Ancient Monuments would also be the first major work in the still-undisciplined disciplines of anthropology and archaeology, and thus unavoidably a landmark in those fieldsand, for that matter, in American science in general (which was then often viewed as the poor stepchild of European science).

All this was riding on a book devoted to the questions of the origin, antiquity, and identity of the moundbuilders. Those questions had surfaced after the Revolutionary War, as emigrant trains began streaming over the Appalachian and Allegheny Mountains into the lowlands of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys (then the American West) and settlers came upon vast numbers of abandoned mounds and earthworks. By then, local Native Americans had been mostly decimated or dispersed by spirituous liquors, the small-pox, war and an abridgment of territory, as Jefferson put it; remaining individuals had neither recollections nor legends of building the earthworks, and their numbers seemed too few to account for the extensive construction that had obviously taken place. The result was that mound construction was widely and popularly attributed to a race of moundbuilders, who either no longer existed or at least no longer existed where and as they had earlier.

There was no single moundbuilder story, but many, and in the first half of the nineteenth century these took a variety of mythic, romantic, and scholarly forms and thrived in a literature of fantasy, bad poetry, antiquarian studies, and best-selling romantic

Nor was it clear how the moundbuilders related to living Native Americans: Were they linked as ancestors and descendants? Was one civilized, the other savage? If so, what caused the apparent tumble from the demi-civilized state of the mound-builders to the savagery of the Indians? Was one vanquished and the other the conqueror? How did the moundbuilders relate to the comparably advanced civilizations of Central and South America? Were those the places where the moundbuilders originated, or were they the refuges of the moundbuilders flight from the encroaching Indians? And how, ultimately, did these distinctive American races relate to the peoples of the Old World?

These were loaded questions to a new nation being swept along in an undirected and uncontrolled social experiment mixing three different races, one savage, another enslaved, the third certain of its racial superiority but hamstrung by an Enlightenment belief in the common humanity of all. The queries also sparked sharp political repercussions in a nation that was expanding westward and that often perceived Indians as brutal, warlike, and savage obstacles to settlement. The idea that Indians themselves drove off or killed the glorious moundbuilders made it easier to rationalize their inevitable demise as a form of historic justice.

These questions were also deeply discomforting to a nation that viewed the past through a biblical lens, yet was confronted with the realization that neither the moundbuilders nor the American Indians were easily identified in the chronicles of Moses. On the presumption of monogenesisthe idea that all the varieties of the human race were descended from a single pair, and that after the Flood the earth was indebted solely to the ark of Noah for the replenishment of man and beastAmerican origins were sought among historically known or imagined groups, among them the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Mongols, Welsh, Hindoos, and Atlanteans. But all these claims, and even the perennial favoritethat the American races were descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel (a claim with two great virtues: It explained who the Indians were and where the Israelites had been lost all those years)failed to withstand close scrutiny. Making matters even more uncomfortable were the polygenists, who through the 1830s and 1840s were arguing with increasing intensity and seemingly insurmountable evidence that the Bible was utterly irrelevant to the question of the origins of the American race (moundbuilder or Indian), for the races of humanity were, in fact, separately created speciesGenesis notwithstanding. As Curtis M. Hinsley argues, the search for human origins had deep religious import.

So it was that the moundbuilder question, a straightforward archaeological issue on its face, at times hovered dangerously close to the raw nerves of religion and racism. Surely, launching the Contributions to Knowledge series with a volume devoted to, say, meteorology, ornithology, or even agricultural chemistry would have No wonder he was nervous.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley»

Look at similar books to Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Ancient Monuments of Mississippi Valley and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.