CATHERINE A . SANDERSON

Copyright 2020 by Catherine A. Sanderson

Names: Sanderson, Catherine Ashley, 1968 author.

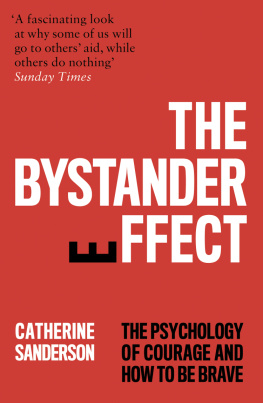

Title: Why we act : turning bystanders into moral rebels / Catherine A. Sanderson.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019045264

Subjects: LCSH: Helping behavior. | Risk-taking (Psychology) | Altruism. | Courage.

On August 25, 2017, my husband and I spent the day settling in our oldest child, Andrew, for the start of his first year at college. We went to Walmart to buy a minifridge and rug. We hung posters above his bed. We attended the obligatory goodbye family lunch before returning to our car to head home to a slightly quieter house.

Two weeks later Andrew called, which was unusual since, like most teenagers, he vastly prefers texting. His voice breaking, he told me that a student in his dorm had just died.

As he described it on the phone, the two of them seemed to have so much in common. They were both freshmen. They were both from Massachusetts and had attended rival prep schools. They both had younger brothers.

What happened? I asked.

He told me the student had been drinking alcohol with friends. He got drunk, and around 9 P.M. on Saturday, he fell and hit his head. His friends, roommate, and lacrosse teammates watched over him for many hours. They strapped a backpack around his shoulders to keep him from rolling onto his back, vomiting, and then choking to death. They periodically checked to make sure he was still breathing.

But what they didnt dofor nearly twenty hours after the fallwas call 911.

By the time they finally did seek help, at around 4 P.M. on Sunday, it was too late. The student was taken to a hospital and put on life support so that his family could fly in to say goodbye.

Now, its impossible to know whether prompt medical attention could have saved his life. Perhaps it wouldnt have. But what is clear is that he didnt get that opportunity. And this storyof college students failing to do anything in the face of a serious emergencyis hardly unusual.

Its not just college students who choose not to act, even when the stakes are high. Why did most passengers sit silently when a man was forcibly dragged off a United Airlines flight, recorded on a video that then went viral? What leads people to stay silent when a colleague uses derogatory language or engages in harassing behavior? Why did so many church leaders fail to report sexual abuse by Catholic priests for so many years?

Throughout my careeras a graduate student at Princeton University in the 1990s and as a professor at Amherst College over the last twenty yearsmy research has focused on the influence of social norms, the unwritten rules that shape our behavior. Although people follow these norms to fit in with their social group, they can also make crucial errors in their perception of these norms. The more I thought about these seemingly disparate examples of people failing to act, the more I began to see the root causes as driven by the same factors: confusion about what was happening, a lack of a sense of personal responsibility, misperception of social norms, and fear of consequences.

I have discovered through my own work that educating people about the power of social norms, pointing out the errors we so often make in perceiving these norms and the consequences of our misperceptions, helps them engage in better behavior. Ive done studies that show that freshman women who learn how campus social norms contribute to unhealthy body image ideals show lower rates of disordered eating later on, and that college students who learn that many of their peers struggle with mental health challenges have a more positive view of mental health services. Helping people understand the psychological processes that lead them to misperceive what those around them are actually thinkingto believe that all women want to be thin, that other college students never feel sad or lonelyreduces the mistakes and misunderstandings we make about other people and can improve our psychological and physical well-being. It can also push us to act.

In my very first introduction to psychology as an undergraduate at Stanford in 1987, I remember being fascinated when I learned how much being in a group influenced our own behavior. I was fortunate enough to have Phil Zimbardowhose Stanford Prison Experiment remains one of the most famous and controversial studies in psychologyas my professor. It was quite an introduction to the field of social psychology!

Back then, researchers could design experiments and measure peoples behavior, but we couldnt penetrate the mechanisms that explained them. We couldnt see what was happening in the brain. Recent breakthroughs in neuroscience have completely changed that. It is now possible to see in real time how certain scenarios, pressures, and experiences play out in the brain. As Ill describe throughout this book, these results have revealed that many of the processes that drive inaction occur not through a careful deliberative process, but at an automatic level in the brain.

My goal in writing this book is to help people understand the psychological factors that underlie the very natural human tendency to stay silent in the face of bad behavior, and to show how significant a role that silence plays in allowing the bad behavior to continue. In the first half of the book, I describe how situational and psychological factors can lead good people to engage in bad behavior (). In the closing chapter I look at strategies we all can useregardless of our personalityto increase the likelihood that we will speak up and take action when we are most needed.

My hope is that providing insight into the forces that keep us from actingand offering practical strategies for resisting such pressure in our own liveswill allow readers of this book to step up and do the right thing, even when it feels really hard. Ultimately, thats the secret to breaking the silence of the bystanderand making sure no one has to wait twenty hours after a serious injury before someone picks up the phone.

On August 11, 2012, a sixteen-year-old girl attended a party in Steubenville, Ohio, with some students from the local high school, including members of the schools football team. She drank a lot, became severely intoxicated, and vomited. Students at the party that night described her as appearing out of it. The next morning, she woke up naked in a basement living room with three boys around her but virtually no memory of the prior night.

Over the next few days, several students who had been at the party posted to social media photographs and videos that vividly illustrated what had happened to the girl: her clothes had been removed, and she had been sexually assaulted. In March 2013 two Steubenville High football players, Trent Mays and Malik Richmond, were found guilty of rape.