Rory Medcalf gives us a fast-paced ride around the worlds newest, and most important, strategic arena. He has done more than anyone to introduce the world to the idea of the Indo-Pacific, and this book is a convincing manifesto for a new vision of connectedness. This is the world with all the difficult bits left in.

Bill Hayton, author of The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia, and Associate Fellow, Chatham House

Rory Medcalf offers deep insights into the origin of the idea of the Indo-Pacific, deconstructs the power dynamics shaping the region and delineates potential pathways to limit the conflict. A rich and rewarding read for anyone interested in a region that promises to define the geopolitics of the twenty-first century.

C. Raja Mohan, Director, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore

Essential reading for any scholar or practitioner seeking to understand the geopolitics of a region that will define all our futures.

Michael J. Green, Center for Strategic and International Studies and Georgetown University, author of By More Than Providence and Arming Japan

All of us struggling to understand great-power competition need to become ambidextrous if we are to develop policies to cope with a rising or a collapsing China, and learning from Rory Medcalfs Contest for the Indo-Pacific is a great place to start.

Kori Schake, Deputy Director-General, International Institute for Strategic Studies

Published by La Trobe University Press in conjunction with Black Inc.

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

www.latrobeuniversitypress.com.au

La Trobe University plays an integral role in Australias public intellectual life, and is recognised globally for its research excellence and commitment to ideas and debate. La Trobe University Press publishes books of high intellectual quality, aimed at general readers. Titles range across the humanities and sciences, and are written by distinguished and innovative scholars. La Trobe University Press books are produced in conjunction with Black Inc., an independent Australian publishing house. The members of the LTUP Editorial Board are Vice-Chancellors Fellows Emeritus Professor Robert Manne and Dr Elizabeth Finkel, and Morry Schwartz and Chris Feik of Black Inc.

Copyright Rory Medcalf 2020

Rory Medcalf asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760641573 (paperback)

9781743821046 (ebook)

Cover design and typesetting by Akiko Chan

Text design by Marilyn de Castro

For Eva

PREFACE

T he 2020s have arrived in a cloak of uncertainty. The world sees a crowded horizon of risk, ranging from the Middle East to Asian waters, from democracies in crisis to the burning impacts of climate change. So a book making claims about the future is a gift to fate.

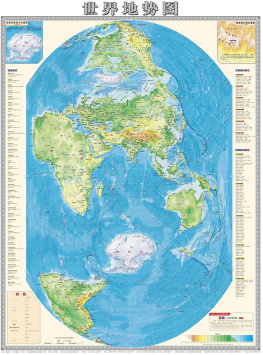

But Contest for the Indo-Pacific is not just about today or tomorrow. It tilts the map to tell a history of international connection and contestation across the seas, tracing deep geopolitical currents to the 2030s and beyond. It ventures conclusions about the risks intrinsic to Chinas hasty regional expansion, the promise of multipolarity as middle players partner up, the staying power of the United States despite Trump and beyond him, and the value of many nations standing firm to help Beijing find a settling point. These judgements should be continuously contested. Each day brings new evidence for and against.

Amid their many travails, the middle players continue to gird themselves for resilience, solidarity and sovereignty. Japan, India and Australia strengthen their bonds with each other and in a quadrilateral with America.

But how long can such middle players hold their ground without American leadership? In late 2019, the US establishment was still saying things allies and partners wanted to hear, with the State Department declaring a shared Indo-Pacific vision, underscoring multilateral institutions and economic development rather than military confrontation with China. Yet the president was somewhere else: skipping the East Asia Summit while demanding South Korea and Japan pay more for US military presence. By the start of 2020, Donald Trump was mired in the rites of impeachment. With a desperate eye on political survival, he was striking a trade truce with Beijing while risking open war with Iran. A different administration one that does not embody constant national emergency is needed for global stability and managing strategic competition with China.

For Xi Jinpings regime will not stand still in combining extreme internal control with geopolitical struggle and reach. Trumps folly is Xis opportunity. Yet the strains are showing for China too. Hints have emerged of internal dissatisfaction with some of Xis largest schemes, whether the material expense of the Belt and Road or the moral cost of the mass incarceration of Uighur people. Hong Kongs defiance has set in. India, too, faces serious internal strife, with Hindu nationalism eroding long-term democratic strengths.

At sea, the contest of power and presence flows and ebbs. Indonesia and Malaysia have greeted the new decade with a stronger defence of their maritime interests against China. American and Japanese warships confidently sail the South China Sea. In the Indian Ocean, China asserts its presence by teaming up variously with Russia, Iran and South Africa for naval exercises. India and France share maritime surveillance information. Indias navy expels a Chinese survey ship from its territories in the Bay of Bengal.

And smaller players cannot be dismissed. In a connected, contested Indo-Pacific, no island is an island. In Australia, the China debate has sharpened. The new leader of Sri Lanka asks China to hand back the Hambantota port and urges other nations to dilute Chinas influence, while celebrating a Chinese-built artificial island off Colombo. Taiwanese democracy is becoming a testing ground for freedom from Chinese Communist Party interference. In the South Pacific, a very different island votes resoundingly for independence in this case from Papua New Guinea in the shadow of its own 20th-century civil war. Bougainville is infrastructure-poor and resource-abundant. Here is one separatism Beijing may welcome fresh terrain in the regional competition for influence.

These are a few examples from the eve of the 2020s. They do not signify trends. But they remind us it is far too soon to conclude that one country will map the future. Decision-makers must peer beyond the parochialism of the present and ask enduring questions about agency, influence, risk and powers many layers. It will be a long game.

Rory Medcalf

Canberra, January 2020

CHAPTER 1

OF NAMES, MAPS AND POWER

O n 11 November 2016, as the globe reeled from Donald Trumps election as US president, two unlikely friends found themselves conversing aboard a shinkansen a Japanese bullet train between Tokyo and Kobe, speeding from sea to sea. Their journey is not yet diplomatic folklore, but it should be.

Aboard the Indo-Pacific express

Abe Shinz, the Japanese prime minister, and Narendra Modi, his Indian counterpart, shared a reputation as strong leaders, driven and charismatic nationalists with a democratic mandate to rouse their sometimes slow-motion countries. Yet they hailed from different sides of the tracks. Modi was proudly from a modest merchant household in Gujarat. Hagiography has it he served chai by a railway station as a child. Abe was the scion of a patrician and conservative political family tied to Japans imperialist past. Stereotypes separated their nations: Japan calm with wealth, technological perfectionism and its declining, ageing populace; India a colourful din of disorder, underdevelopment and a demographic of youth and growth. Even if these were cliches, Tokyo and Delhi surely remained in different worlds, with divergent problems and priorities. Through the modern era in which Modi-ji and Abe-san had grown up, their countries had little contact.

Next page