Contents

Page List

Guide

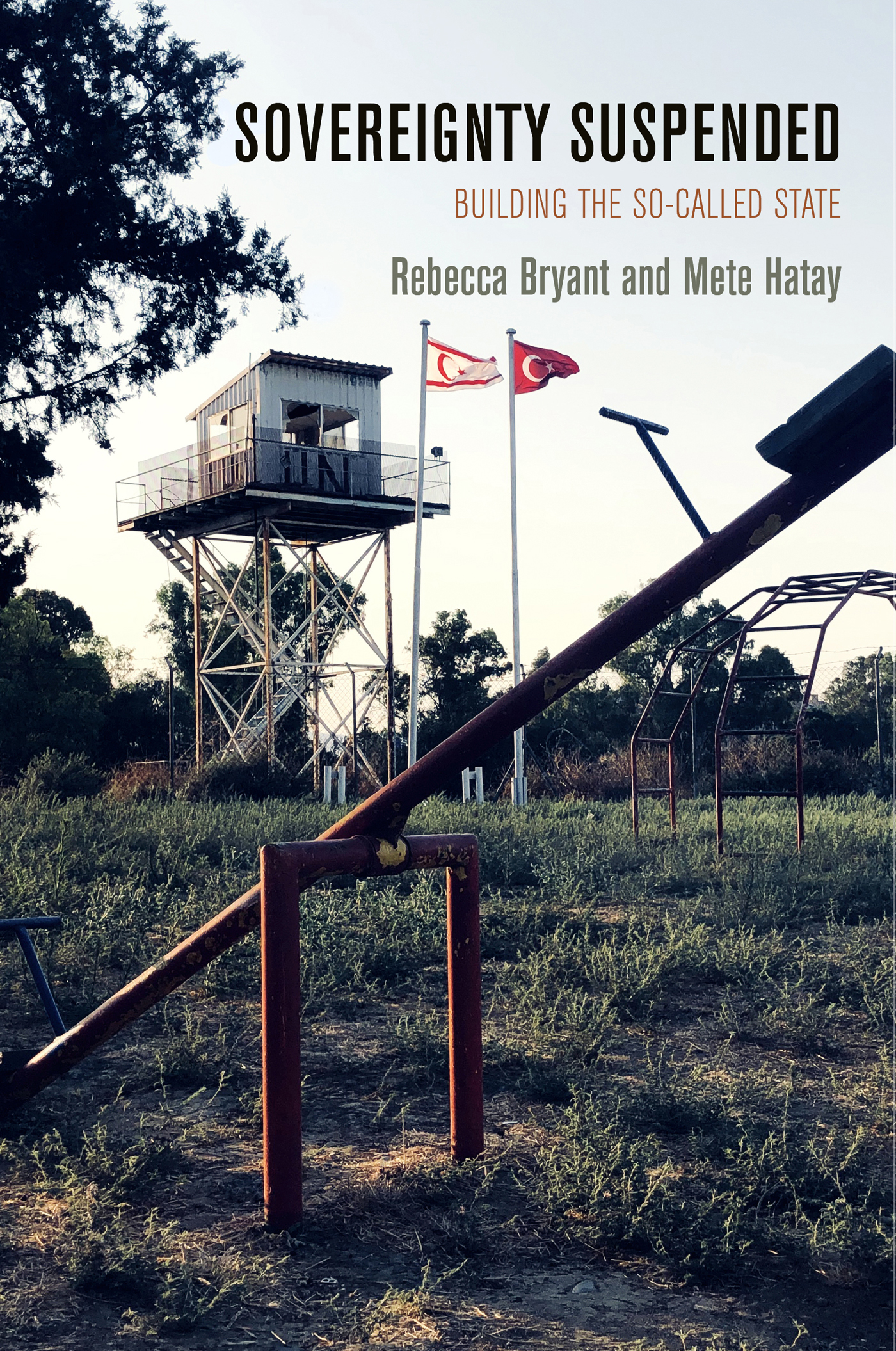

Sovereignty Suspended

THE ETHNOGRAPHY OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE

Series Editors: Daniel J. Hoffman, Tobias Kelly, Sharika Thiranagama

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

SOVEREIGNTY SUSPENDED

Building the So-Called State

Rebecca Bryant and Mete Hatay

Copyright 2020 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bryant, Rebecca, author. | Hatay, Mete, author.

Title: Sovereignty suspended : building the so-called state / Rebecca Bryant and Mete Hatay.

Other titles: Ethnography of political violence.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2020] | Series: The ethnography of political violence | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019045157 | ISBN 978-0-8122-5221-7 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Nation-buildingCyprus, Northern. | Self-determination, NationalCyprus, Northern. | TurksCyprusSocial conditions. | Cyprus, NorthernPolitics and government. | Cyprus, NorthernInternational status. | Cyprus, NorthernForeign relations.

Classification: LCC DS54.95.N67 B79 2020 | DDC 956.93dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019045157

In memory of zer Hatay (19372013)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

It would be a great understatement to call this work a collaboration. Every observation, every idea, every argument emerged out of a shared experience and joint vision of what it means to live in an unrecognized state. The work began in the pleasure of recognizing similar ways of seeing and thinking about that experience and the sense that we could accomplish so much more by thinking about it together. That thinking began in 2006 when Rebecca received seed funding from George Mason University, where she was then teaching, to begin research for a project on governmentality and sovereignty conflicts. Her interest at the time was in how the institutional entrenchment of de facto states shapes the present of unresolved conflicts and constrains negotiations to resolve them. This led to exploratory research in Sri Lanka and Abkhazia, but as an anthropologist she found herself pulled back to the case that she knew best, north Cyprus.

By that time Rebecca had already written one book and was finishing a second about the island, but the collaboration with Mete began in 2007, when on a sabbatical in Cyprus they wrote their first journal article together. That article dealt with a subject that had long intrigued Rebecca, namely, the social forgetting of the 19631974 period, in which Turkish Cypriots lived in militarized enclaves and for five years were under siege. While that period was widely regarded as the most critical period in Turkish Cypriot history, there were no memoirs, books of oral history, or even stories or poems that described the period. While Rebecca had been intrigued by this process of social forgetting, Mete pointed out the reverberations of that period in the present, resulting in an article that reversed many standard interpretations of a time of Turkish Cypriot protest and political action in the early 2000s (Hatay and Bryant 2008). We saw that period of agency against Turkey and action in favor of reunification as one that referenced the enclave period, a period of both deprivation and strong solidarity. Building on that argument, we published a second article that asked what agency under the siege experienced during the first five years of the enclave period can tell us about constructions and simulations of sovereignty (Bryant and Hatay 2011). As a result of those two articles, we initially began this book as an exploration of state-building in the enclaves.

The state-within-a-state that developed then could not be explored, however, without going further back in time and linking Turkish Cypriots minority status under colonial rule to a struggle for institutional representation and what we call sovereign agency that ultimately led to the creation of a de facto state. Our genealogical approach to the contradictions and paradoxes of life in an unrecognized state also suited us both, since we had each separately conducted historical as well as ethnographic research in Cyprus in the past and so knew that many of the contradictions and paradoxes that we encountered in everyday life had much longer histories. For example, the present-day discourse about becoming a minority and disappearing, which we discuss in our first article together, in fact had a much longer history going back to the late nineteenth century. The archival and ethnographic research specifically for this work took place over about seven years and continued through the three years of writing, although the research has been layered over time and builds on the accumulated body of our previous work. That body of work includes research in various archives in Cyprus, Istanbul, Athens, and London, as well as interviews and ethnographic research dating back to the early 1990s. It includes Rebeccas ethnographic and archival research for her second book on Cyprus, The Past in Pieces: Belonging in the New Cyprus, which took as its site a particular region of the islands north and the changes that it experienced after 2003, when the checkpoints that divide the island opened.

Tracing Turkish Cypriots institutional drive over several decades, however, began a long road of new research that took us into the hitherto unexplored archives of the Turkish Cypriot Federation of Institutions (Kbrs Trk Kurumlar Federasyonu) from the 1950s and Turkish Cypriot parliament minutes from the 1970s. It also led us to explore thousands of pages of newspapers from Cyprus and Turkey from the 1950s to the present. It meant dozens of interviews with persons involved in the unrecognized states founding and in its political parties, especially persons engaged in the original distribution of properties after 1974. It meant around three hundred formal and informal interviews with persons displaced during the conflict and ultimately resettled in the islands north, as well as a set of thirty interviews with journalists, union leaders, and civil society representatives about Turkish Cypriots relations with Turkish nationals and with Turkey. All interviews and almost all written sources used for the book were originally in Turkish, and Rebecca was responsible for all translations from Turkish to English.

One of the most important sources, however, has been participant observation over more than a decade, during which we noted down anecdotes, observations of friends, discussions in which we participated, and other ethnographic material. These ethnographic examples appear in the text primarily as unattributed examples, both because the size of the community means that it is very easy to identify persons through description, and also because in long-term fieldwork one may observe interlocutors changing their minds, positions, and political affiliations over time. Alternatively, people may express in private views that they do not want publicly aired in ways that would reveal their source. As should become clear throughout the book, such contradictions are part and parcel of living with a state that is not supposed to be one. Because we live at least half of the year in Cyprus, we also lived with those paradoxes, and we watched our friends and family struggle with them. We watched them grapple with how to build lives, plan for the future, and negotiate their status as citizens of a so-called state. The shape of the present book eventually emerged as we realized that the contradictions and paradoxes of life in an unrecognized state that particularly engaged us would be best explored by focusing our attention on de facto state-building in the post-1974 period.