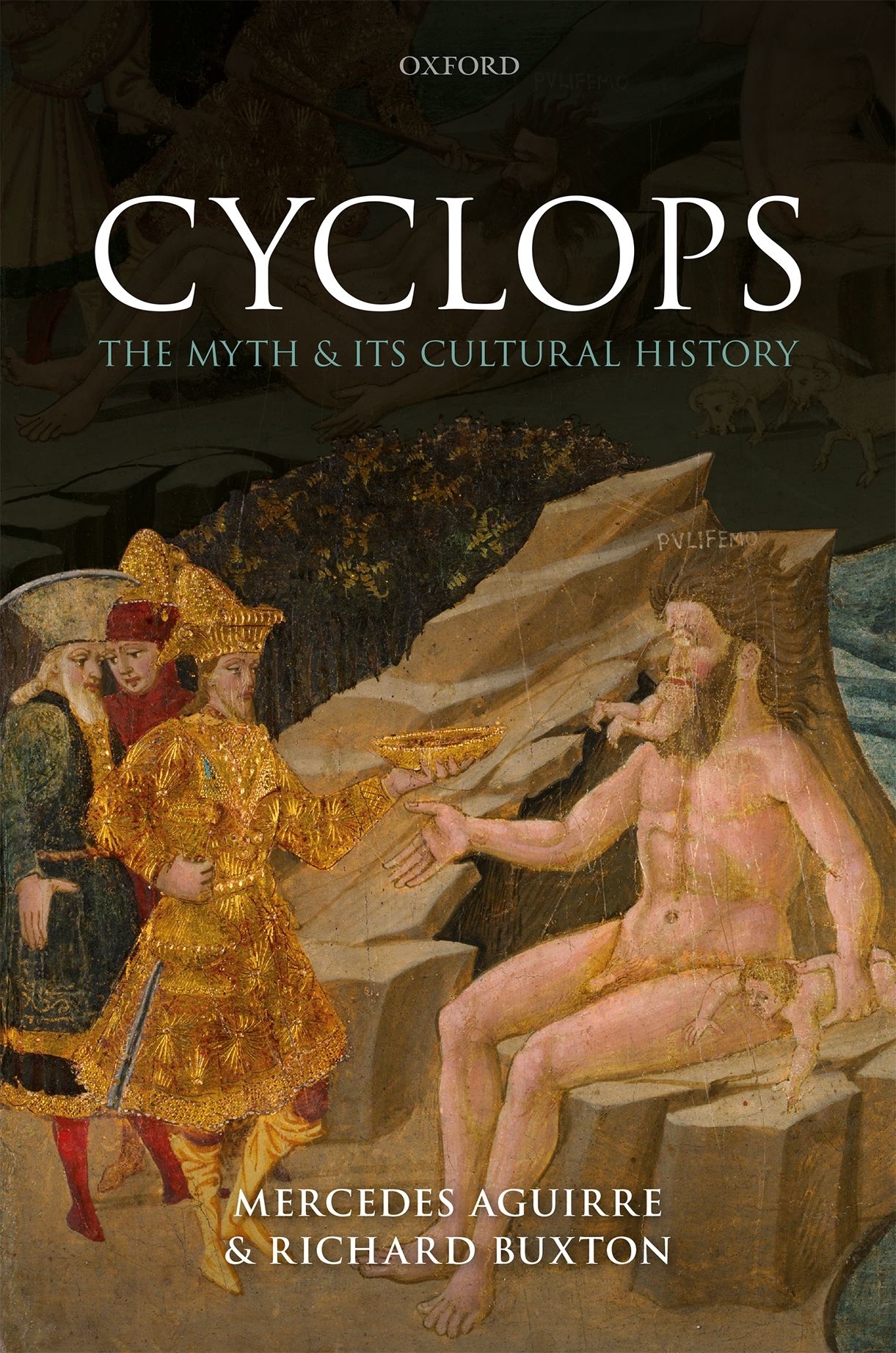

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

Tucked away in a pleasantly shady corner of the Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, just across the road from the Caf Le Rostand, the Fontaine Mdicis features a grotto containing a group of figures sculpted in the 1860s by Auguste Ottin. Polyphemus, huge and Michelangelesque in bronze, with a cloak of bulls hide slung around his shoulders, kneels on a crag above a cave, and looks down. Below him he spies the nymph he adores, Galatea, near naked and swooning in the arms of a beautiful youth. The white marble in which the pair are carved is the only chaste thing about them; all the rest is passion. Oblivious of everything but each other, they little realize that their happy present will have no future, for Polyphemus wrath will destroy their idyll, even though Acis, the beautiful young man in question, is destined for everlasting, watery renewal in the form of a river.

The seed from which the present book grew was sown a decade ago during a visit that the authors made to this Parisian grotto. As we looked at Ottins sculptural group, we wondered whether anyone had yet made a detailed study of the development of Cyclopean myths from antiquity until today. In due course we discovered that, to the best of our knowledge, no such study existed, or at least nothing that dealt with the material in the way we thought illuminating. What follows is a gesture towards filling that gap. We are under no illusions about the difficulty of the task, especially in relation to post-classical receptions of these myths. In that area we are almost always out of our comfort zone, so our debt to our predecessors is especially heavy. In spite of the challenges, however, we thought it better to try than not to.

In principle, the work has been divided: Aguirre has focused on ancient and modern art, gardens, and grottoes, Buxton on most of the rest, especially the literary texts, both ancient and modern. But every word written by the one has been revised by the other, so that responsibility for the outcome is shared. Moreover, the whole project has proceeded as a dialogue, so that at this stage it would be impossible, as well as pointless, to try to disentangle who thought of what first.

Preliminary versions of our ideas have been presented to audiences in Bristol, Cambridge, Colchester, Delphi, Edinburgh, Leiden, odz, London, Madrid, and Oxford; we are grateful to all who gave us the benefit of their comments on those occasions. Two other settings, each in its own way an ideal environment for research and reflection, have helped us to develop our ideas: the Fondation Hardt near Geneva, where we spent several delightfully productive weeks, and Clare Hall, Cambridge, where we had the honour to be elected to six-month Visiting Fellowships. The colleagues whom we met in both institutions showed marvellous patience in putting up with our relentless chatter about one-eyed (or two-eyed, or three-eyed) ogres.

In spite of the radical changes in research methods implied by the resources of the internet, it is still true that, especially for those studying topics in the humanities, to work in a library stocked with physical books remains a fundamental method of investigation. We therefore express our gratitude to the unfailingly courteous and efficient staff of, in the UK, the University Libraries of Bristol and Cambridge, and, in Spain, the libraries of the Universidad Complutense and the Deutsches Archologisches Institut in Madrid.

In order to bring our arguments more vividly home to the reader, we wished to include a substantial number of illustrations. But images, and especially the permissions to reproduce them, do not come cheap. We were therefore extremely lucky to receive financial help towards covering these costs from Asteria: Asociacin Internacional de Mitocrtica.

Finally, it is our pleasure to single out and warmly thank some individuals. Michael Wright gave us valuable insights into the practices of blacksmiths and other metalworkers. Michael Trapp pointed us towards the importance of Salomon and Isaac de Caus, while Ellen OGorman expertly interpreted for us the music that Salomon attributed to Polyphemus, and even sent us a recording of her own sprightly performance of it on the recorder. Ian Jenkins put at our disposal his unrivalled knowledge of Sir William Hamilton. We had valuable advice from Pantelis Michelakis and Luis Unceta about the relationship between classical antiquity and cinema. On certain linguistic matters our patient mentors were James Claxton and Torsten Meissner. Others whose expertise we shamelessly exploited were Domenico Accorinti, Adriano Aymonino, Alberto Bernab, Jan Bremmer, Judith Bryce, John Carey, Paul Cartledge, Stephen Clark, Cristina Delgado Linacero, Filip Doroszewski, Ana Gonzlez-Rivas, Tonio Hlscher, Pascale Linant de Bellefonds, Michael Liversidge, Geoffrey Lloyd, Jos Manuel Losada, Gina Muskett, Derek Offord, Susanna Phillippo, Jonathan Prag, Michael Reeve, Rush Rehm, Brendan Smith, Michael Squire, Susan Stephens, and Luigi Venezia. We absolve all of them from any responsibility for the use to which we have put their guidance. We also record our gratitude to Charlotte Loveridge and Georgie Leighton of Oxford University Press, both for their faith in our project and for their near-saintly patience in waiting for it to be completed; likewise to Hilary Walford, for her keen-eyed excellence in the art of copy-editing, and to Erica Martin and Rosanna van den Bogaerde, for their exemplary skill in picture research. On a different note, the artist Gema Navarro Goig generously presented us with a magnificent woodcut of the Cyclops that she had created for us. We are profoundly in her debt.

M.A.

R.G.A.B.

Madrid and Clevedon

Contents

Further details of items marked Cat. can be found in the Catalogue on pp. 377382.