Intelligence Stuart Ritchie |  |

For my parents

Contents

About the author

Dr Stuart J. Ritchie is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology in The University of Edinburghs Department of Psychology. His research focuses on how intelligence develops and changes across the lifespan, what might influence it in childhood, and how we might prevent it from declining in later life. His studies of intelligence have been published in journals such as Psychological Science, Current Biology, Child Development and Intelligence.

Acknowledgements

As luck would have it, I know some very smart people who have helped immensely with this book. Im grateful to George Miller for suggesting I try my hand at writing it, and to Edinburgh Skeptics for hosting my first talk on intelligence, which formed an outline for the topics discussed here. Iva ukic, Ian Deary, Katharine Atkinson and Andrew Sabisky all made extremely useful comments on earlier drafts, and during the writing I benefited greatly from discussions with Rogier Kievit, Michael Story and Tim Bates, among many others. Any less-than-intelligent errors in the book are mine alone.

All the graphs in the book were made by the author, using Hadley Wickhams ggplot2 package in R. I thank Mark Bastin for providing the brain image in .

Introducing intelligence

There is an unusually high and consistent correlation between the stupidity of a given person and [their] propensity to be impressed by the measurement of IQ.

Christopher Hitchens, The Nation

Smart people dont like the idea of intelligence. Just mention IQ in polite company, and youll be informed (sometimes rather sternly) that IQ tests dont measure anything real, and reflect only how good you are at doing IQ tests; that they ignore important things like multiple intelligences and emotional intelligence; and that those who are interested in intelligence testing must be elitists, or perhaps something more sinister.

But anyone who makes these arguments simply hasnt seen the scientific evidence. The research shows that intelligence test scores are meaningful and useful; that they relate to education, occupation and even health; that they are genetically influenced; and that they are linked to aspects of the brain. Studies of intelligence and IQ are regularly published by psychologists, neuroscientists, geneticists, psychiatrists and sociologists in the worlds top scientific journals. Pace Christopher Hitchens (see previous page), we really should be impressed with the measurement of IQ. The purpose of this book is to give an up-to-date summary of the modern science of intelligence, and answer the common questions that are asked about it. Well start off with the most obvious question of all

What is intelligence?

Sceptics of intelligence research often make their opening gambit by asking this deceptively simple question: How do you even define intelligence? The implication is that, if researchers cant give a snappy definition of intelligence, they cant possibly claim to measure it using IQ tests. Here is one attempt at a definition (Gottfredson, 1997):

Intelligence is a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience. It is not merely book-learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather, it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings, catching on, making sense of things, or figuring out what to do.

OK, not particularly snappy. But it would be surprising if something as complicated as human intelligence could be summed up in a brief soundbite. The definition above describes a mental capacity that everyone has to a degree, but whats crucial for our discussion in this book is that not everyone has the same capacity: some people are more intelligent than others. Its these intelligence differences that are studied in most IQ research, and that are noticed in schools, in workplaces, and in everyday life.

A potted history of intelligence testing

It took a surprisingly long time for people to think about measuring differences in intelligence. Its not as if intelligence is a new concept: notably smart people have been written about since at least the ancient Greeks (consider, for instance, what set Odysseus apart from the other mythological heroes). Philosophers have discussed human faculties for centuries. One popular conception, attributed to Aristotle, was the five wits: imagination, fantasy, memory, reason and the common sense. These were mentioned by Aquinas in the thirteenth century, Chaucer in the fourteenth and Shakespeare in the sixteenth; some of them were hazily analogous to what scientists would now consider cognition (see Deary, 2000, for some other historical examples). Again, though, for a remarkably long time, little thought was given to how one might measure the differences between people in these attributes.

The psychologist Arthur Jensen (1998) suggested two reasons for this. The first is that rationality was often seen as something divine that could only fleetingly be tapped into by humans: if reason was a gift from God, it didnt make sense to try to measure it. The second is that, until relatively recently, few people were formally schooled; education is the context where intelligence differences are most in evidence, and if only a privileged few attended school, there wasnt much opportunity to notice or to consider measuring these differences.

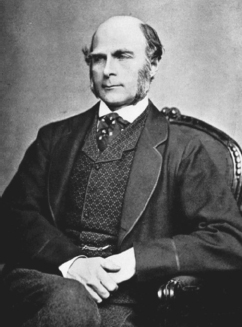

It may be no coincidence, then, that the mid-to-late nineteenth century, which saw compulsory education laws introduced across Europe, was the period where testing intelligence was first seriously considered. Perhaps appropriately, the first steps were made by a true genius: Charles Darwins half-cousin, Sir Francis Galton ().

Figure 1.1 Sir Francis Galton (18221911) in middle life. (Plate lxi from K. Pearson, 1914.)

Polymath doesnt even begin to cut it with Galton: its hard to exaggerate the sheer variety (and, sometimes, eccentricity) of the contributions he made to human knowledge. He invented indispensible statistical concepts (two of which are discussed below), as well as the science of fingerprinting, weather maps, the dog whistle, and the idea of crowdsourcing; he even had time to explore and map previously unknown parts of Africa. Fascinated with measuring and enumerating everything it was possible to measure and enumerate from the levels of boredom displayed by the tilting heads of students in his colleagues lectures, to the relative attractiveness of women on the streets of various British cities (London came first, and Aberdeen came last, in case youre wondering) Galton began to reflect on eminence. What was it that made some people rise to the top in society? Why did some families seem to have many eminent individuals while others had none?

Next page

What is intelligence?

What is intelligence?

Figure 1.1 Sir Francis Galton (18221911) in middle life. (Plate lxi from K. Pearson, 1914.)

Figure 1.1 Sir Francis Galton (18221911) in middle life. (Plate lxi from K. Pearson, 1914.)