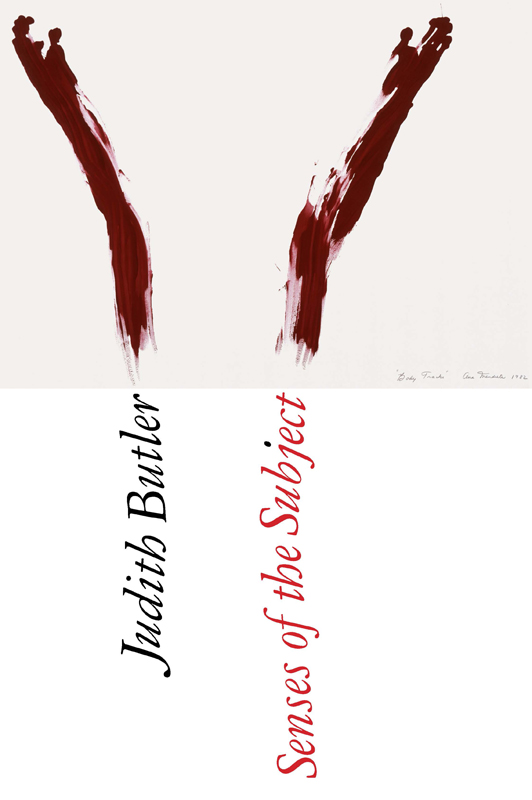

Butler - Senses of the Subject

Here you can read online Butler - Senses of the Subject full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;NY, year: 2015, publisher: Fordham University Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Senses of the Subject: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Senses of the Subject" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Senses of the Subject — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Senses of the Subject" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Senses of the Subject

Copyright 2015 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at catalog.loc.gov.

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

First edition

CONTENTS

I would like to thank the late and unforgettable Helen Tartar and Fordham University Press for making this collection possible, Zoe Weiman-Kelman and Aleksey Dubilet for helping with the manuscript preparation, and Bud Bynack for his tenacious and arresting editing. This tentative book is dedicated to Denise Riley, without whose thoughts I would not have very many of my own.

Although these texts evince overlapping and emergent themes, they differ substantially, given the nineteen years that passed between the earliest and the most recent writings included here (Kierkegaard in 1993 and Hegel in 2012). These essays were first printed in the following publications:

How Can I Deny that These Hands and This Body Are Mine?, Qui Parle 11, no. 1 (1998); reprinted in expanded form in Material Events: Paul de Man and the Afterlife of Theory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001); Kierkegaards Speculative Despair, in Robert Solomon and Kathleen Higgins, eds., German Idealism (London: Routledge, 1993); Merleau-Ponty and the Touch of Malebranche, in Taylor Carmen, ed., Merleau-Ponty Reader (London: Cambridge, 2005); Sexual Difference as a Question of Ethics, in Laura Doyle, ed., Bodies of Resistance (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2001); Spinozas Ethics under Pressure, in Victoria Kahn, Neil Saccamano, and Daniela Coli, eds., Politics and Passions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006); Violence, Nonviolence: Sartre on Fanon, Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 27, no. 1 (2006); reprinted in Jonathan Judaken, ed., Race after Sartre , (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2008); To Sense What Is Living in the Other: Hegels Early Love , dOCUMENTA (13) Notebooks, no. 66 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012) (bilingual edition, English and German).

Judith Butler, Berkeley, 2014

Senses of the Subject

This volume represents an array of philosophical essays that I have written over the a period of twenty years (19932012), registering some shifts in my views over that period of time. If I am asked to say what, if anything, rationalizes this collection, I could only answer in a faltering way. If there is a sense to be discerned from that faltering, it would probably be this: when we speak about subject formation, we invariably presume a threshold of susceptibility or impressionability that may be said to precede the formation of a conscious and deliberate I. That means only that this creature that I am is affected by something outside of itself, understood as prior, that activates and informs the subject that I am. When I make use of that first-person pronoun in this context, I am not exactly telling you about myself. Of course, what I have to say has personal implications, but it operates at a relatively impersonal level. So I do not always encumber the first-person pronoun with scare quotes, but I am letting you know that when I say I, I mean you, too, and all those who come to use the pronoun or to speak in a language that inflects the first person in a different way.

My point is to suggest that I am already affected before I can say I and that I have to be affected to say I at all. Those straightforward propositions fail, though, to describe the threshold of susceptibility that precedes any sense of individuation or linguistic capacity for self-reference. One could say that I am suggesting simply that the senses are primary and that we feel things, undergo impressions, prior to forming any thoughts, including any thoughts we might have about ourselves. That characterization would be true of what I have to say, but it would not fully enough explain what I hope to show.

First, I am not sure whether there are certain kinds of thoughts that operate in the course of sensing something. But second, I want to underscore the methodological problem that emerges for any such claim about the primacy of the senses: if I say that I am already affected before I can say I, I am speaking much later than the process I seek to describe. In fact, my retrospective position casts doubt on whether or not I can describe this situation at all, since strictly speaking, I was not present for the process, and I myself seem to be one of its various effects. Further, it may be that retroactively, I reconstitute that origin according to whatever phantasm grips me, and so you will receive an account only of my phantasm, not of my origin. Given how vexed they are, one might think we should all remain silent on such matters, avoiding the first person altogether, since the indexical function fails precisely at the moment in which we want to marshal its forces to help us describe something difficult. My suggestion, rather, is that we accept this belatedness and proceed in a narrative fashion that marks the paradoxical condition of trying to relate something about my formation that is prior to my own narrative capacity and that, in fact, brings that narrative capacity about.

Let us follow Nietzsches well-known remark that the bell that has boomed the twelve beats of noon startles the self-reflective person who only afterward rubs his ears and, surprised and disconcerted, asks, what really was that which we have just experienced? It may be that this kind of belatedness, what Freud called Nachtrglichkeit, is an inevitable feature of inquiries such as these, inflecting the narration with the historical perspective of the present. Still, is it possible to try to give a narrative sequence for the process of being affected, a threshold of susceptibility and transfer and I that might reflect upon and relay, a life that did not yet exist and that, in part, accounts for the emergence of that I?

Certain literary fictions rely on these kinds of impossible scenarios. Consider the rather fantastic beginning of David Copperfield, in which the narrator speaks with extraordinary perspicacity about the details of ordinary life preceding and including his own birth. He mentions parenthetically that he has been told the story of his birth and that he believes what he has been told, but as the narration proceeds, he ceases to relay the story as if it were authored by someone other than himself; he has inserted himself as a knowing narrator at the very outset of his life, a way perhaps to get around the difficulty of once having been an infant unable to speak, reflect, or think as an adult author does. A certain denial of infancy seeps into his ever more authoritative account of when he cried and what others thought and did on that occasion.

Indeed, the opening chapter is fantastically entitled I Am Born, and the very first line throws down the gauntlet: Will this narrator be authored, or will he author himself? The novel opens: Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show. There is, of course, a double irony, given that the narrator is a fictional construct of Charles Dickens and so already and continuously authored, even as he poses this question, suggesting that he might be able to leap out of the text that supports his fictional existence. Even within the terms of the novel, it is obvious that he could not have offered a report on his own birth with any kind of first-hand authority, and yet he proceeds with this impossible and seductive undertaking precisely as if he were there, looking on, as it were, as he enters the world.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Senses of the Subject»

Look at similar books to Senses of the Subject. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Senses of the Subject and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.