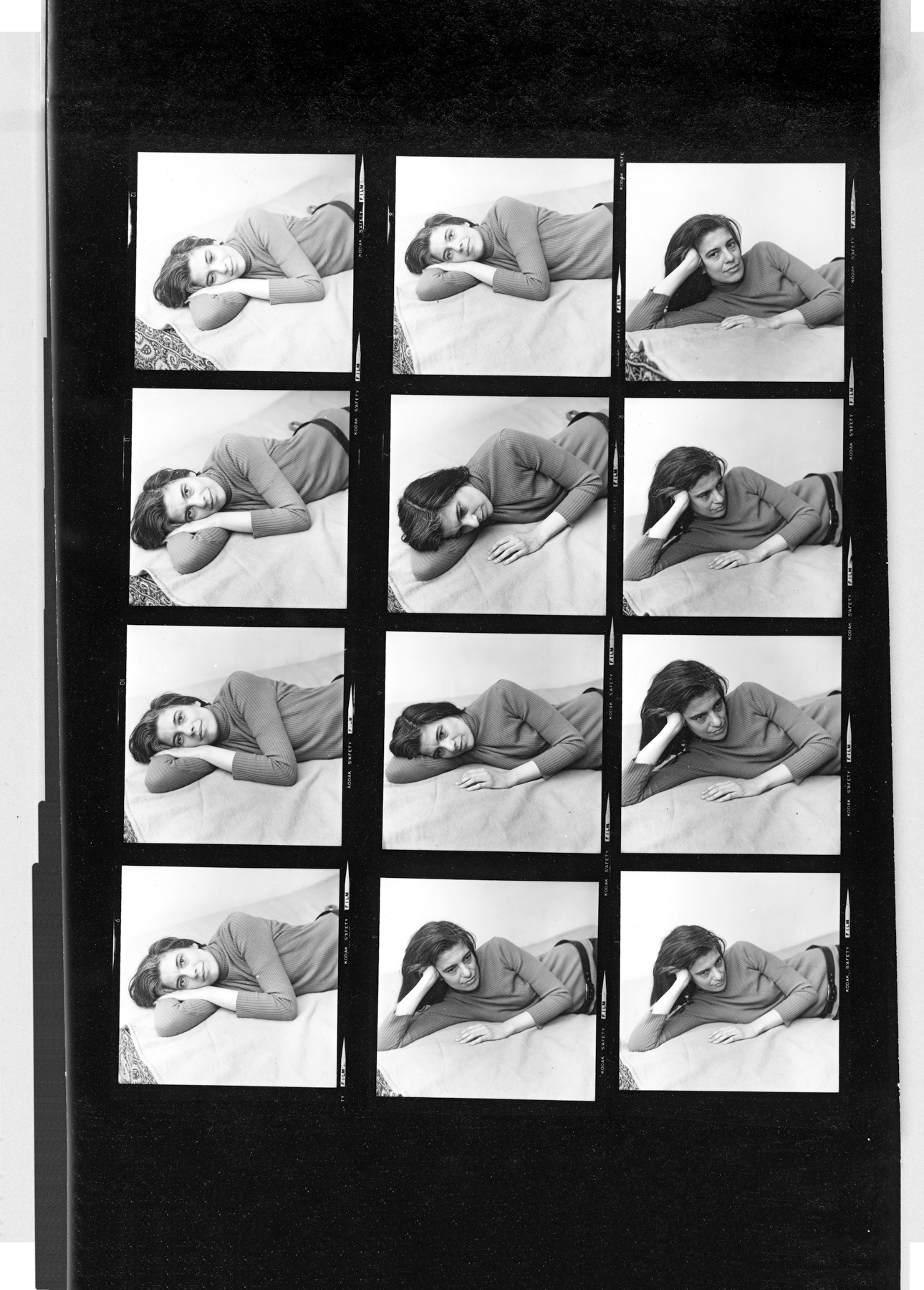

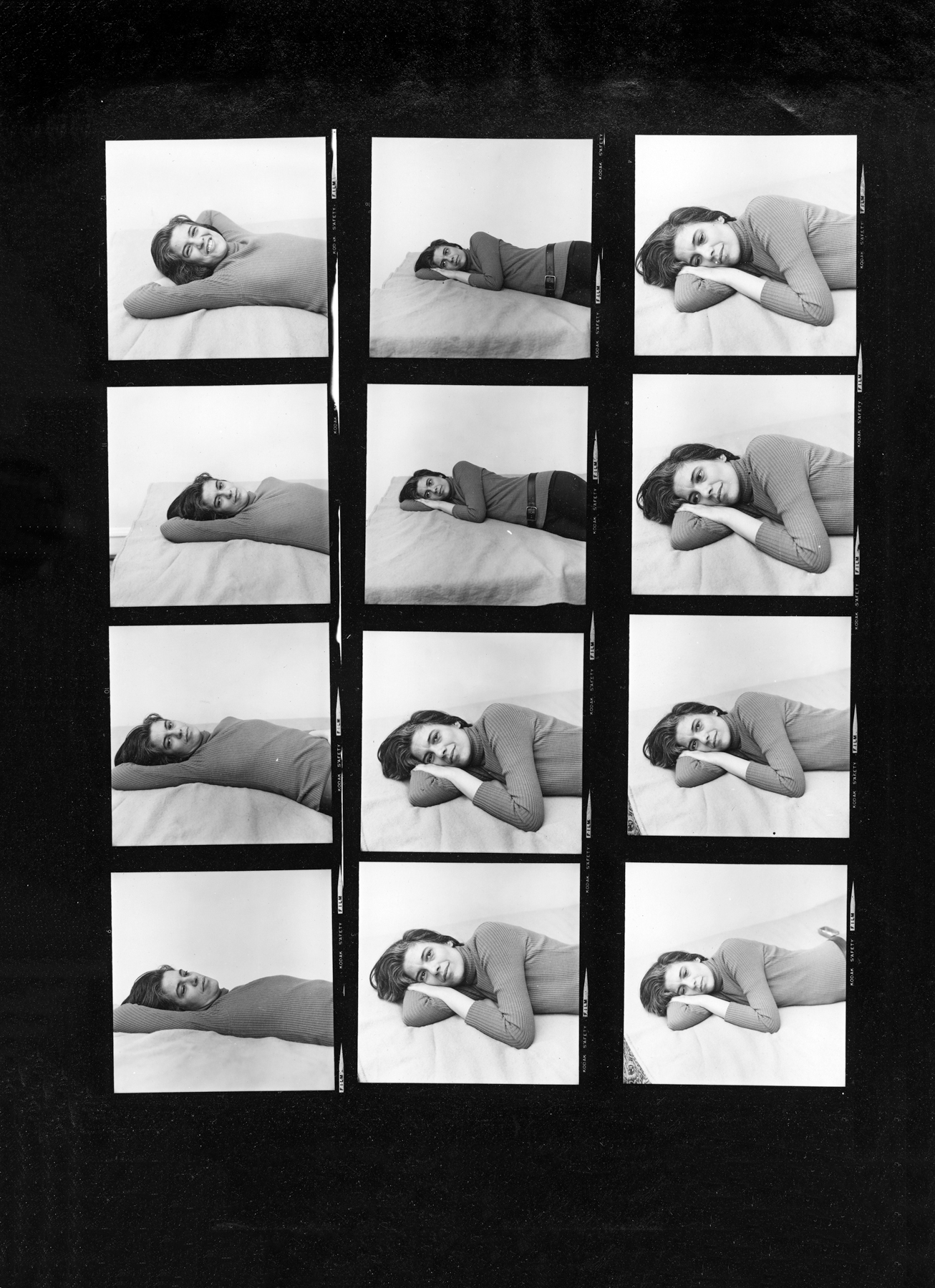

Auction of Souls, Sarah Leah Jacobson and daughter Mildred. Susan Sontag Papers (Collection 612). Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA.

I n January 1919, in a dry riverbed north of Los Angeles, a cast of thousands gathered to re-create a contemporary horror. Based on a book published a year before by a teenage survivor of the Armenian massacres, Auction of Souls, alternatively known as Ravished Armenia, was one of the earliest Hollywood spectaculars, a new genre that married special effects and extravagant expense to overwhelm its audience. This one would be all the more immediate, all the more powerful, because it incorporated another new genre, the newsreel, popularized in the Great War that had ended only two months before. This film was, as they say, based on a true story. The Armenian massacres, begun in 1915, were still going on.

The dry sand bed of the San Fernando River near Newhall, California, turned out to be the ideal location, one trade paper said, to film the ferocious Turks and Kurds driving the ragged army of Armenians with their bundles, and some of them dragging small children, over the stony roads and byways of the desert. Thousands of Armenians participated in the filming, including survivors who had reached the United States.

For some of these extras, the filming, which included depictions of mob rapes, mass drownings, people forced to dig their own graves, and a sweeping panorama of women being crucified, proved too much. Several women whose relatives had perished under the sword of the Turk, the chronicler continued, were overcome by the mimic spectacles of torture and infamy.

The producer, he went on to note, furnished a picnic luncheon.

* * *

One image from that day shows a young woman in flowery garb with a large carpetbag on her arm. Amid makeshift refugee tents, and with an afflicted expression on her face, she stands comforting a girl. Neither dares look at the sinister shadows approaching, invisible men with upraised arms, aiming something at them. Perhaps the women are about to be shot. Perhaps, given the panoply of available tortures, death by gunshot is the least painful option.

Gazing at this devastated corner of Anatolia, we are relieved to recall that it is, in fact, a film location in Southern California, and that the long shadows belong not to marauding Turks but to photographers. Despite press releases to the contrary, the Armenians being filmed were not all Armenians: this pair, for example, turns out to be a Jewish woman named Sarah Leah Jacobson and her thirteen-year-old daughter, Mildred.

If knowing that the picture is staged makes it less poignant, another fact, which neither subjects nor photographers could have known, does not. Though they returned home to downtown Los Angeles after playing their part in the mimic spectacles of torture and infamy, Sarah Leah would be dead a little more than a year later, aged thirty-three. This picture of bereavement would be the last surviving image of her with her daughter.

Mildred would never forgive her mother for abandoning her. But abandonment was not Sarah Leahs only legacy. In her short life, she traveled from Biaystok, in eastern Poland, where she was born, to Hollywood, where she died. Mildred, too, would be adventurous. She married a man born in New York who reached China by nineteen, where he traveled into the Gobi Desert and bought furs from Mongolian nomads. Like Sarah Leahs, his precocious start was cut short; he, too, died at thirty-three.

Their daughter, named Susan Lee in an Americanized echo of Sarah Leah, was five when her father died. She only knew him, she later wrote, as a set of Photograph.

* * *

Photograph, Mildreds daughter Susan wrote, state the innocence, the vulnerability of lives heading toward their own destruction. That most people standing before the lens are not thinking about their impending destruction makes pictures more, rather than less, affecting: Sarah Leah and Mildred, acting out a tragedy, did not see that their own was so swiftly approaching.

Neither could they have known how much Auction of Souls, meant to commemorate the past, looked to the future. It is spookily appropriate that the last photograph of Susan Sontags mother and grandmother should be connected to an artistic reenactment of genocide. Troubled all her life by questions of cruelty and war, Sontag would redefine the ways people look at images of suffering and ask what, if anything, they do with the images they see.

The problem, for her, was not a philosophical abstraction. As Mildreds life was shattered by the death of Sarah Leah, Susans, by her own account, was also split in two. The breach occurred in a Santa Monica bookstore, where she first glimpsed Photograph of the Holocaust. Nothing I have seenin Photograph or in real lifeever cut me as sharply, deeply, instantaneously, she wrote.

She was twelve. The shock was so great that for the rest of her life she would ask, in one book after the next, how pain could be portrayed, and how it could be endured. Books, and the vision of a better world they offered, saved her from an unhappy childhood, and whenever she was faced with sadness and depression, her first instinct was to hide in a book, head to the movies or the opera. Art might not have made up for lifes disappointments, but it was an indispensable palliative; and toward the end of her life, during another genocidethe word invented to describe the Armenian calamitySusan Sontag knew exactly what the Bosnians needed. She went to Sarajevo, and she put on a play.

* * *

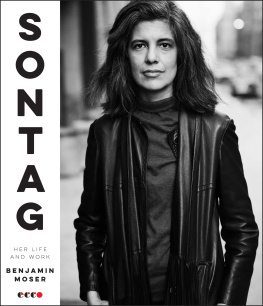

Susan Sontag was Americas last great literary star, a flashback to a time when writers could be, more than simply respected or well regarded, famous. But never before had a writer who bemoaned the shortcomings in Georg Lukcss literary criticism and Nathalie Sarrautes theory of the nouveau roman become as prominent, as quickly, as Sontag did. Her success was literally spectacular: played out in full public view.

Tall, olive-skinned, with strongly traced Picasso eyelids and serene lips less curled than Mona Lisas, Sontag attracted the cameras of the greatest photographers of her age. She was Athena, not Aphrodite: a warrior, a dark prince. With the mind of a European philosopher and the looks of a musketeer, she combined qualities that had been combined in men. What was new was that they were combined in a womanand for generations of artistic and intellectual women, that combination provided a model more potent than any they knew.

Her fame fascinated them in part because it was so unprecedented. At the beginning of her career, she was incongruous: a beautiful young woman who was intimidatingly learned; a writer from the hieratic fastness of the New York intellectual world who engaged with the contemporary low culture the older generation claimed to abhor. She had no real lineage. And though many would fashion themselves in her image, her role would never be convincingly filled again. She created the mold, and then she broke it.