WATERLOO 1815

This edition published in 2015 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright John Grehan, 2015

The right of John Grehan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-78383-199-9

eISBN: 9781848329157

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please email: info@frontline-books.com,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Contents

Introduction

The past is a foreign country

T he Battle of Waterloo has been the subject of thousands of books, pamphlets, magazines and journals. Indeed, 18 June 1815, is the single most documented and discussed day in history and therein lies the problem. Which amongst this vast assortment are those that can be relied upon to present us with the unbiased truth. It might be assumed that history is a succession of acknowledged facts and that it is the function of the historian merely to gather those facts together and present them to his or her readers in a comprehensible form. This is on the presumption that most contemporary commentators record the event that they are witnessing with a reasonable degree of accuracy and honesty, otherwise historians would have no basis at all to work from. Of course, this is sometimes far from being the case.

Firstly, any conclusions drawn from contemporary comments would have to be tempered by known or assumed prejudice or predisposition. How and to what degree such influences affect the individual can, at best, only be estimated. Added to this is the fact that, as we all know from experience, not everyone witnessing an event will agree in detail on what they have seen. Also, when the mists of time mingle with the fog of war our ability to discern the reliability or otherwise of those witnesses is considerably obscured.

These problems were recognised by Napoleon who knew only too well that his actions would be the subject of much historical examination:

Historical fact, which is so often invoked, to which everyone so readily appeals, is so often a mere word: it cannot be ascertained when events actually occur in the heat of contrary passions; and, if later on, there is a consensus, this is only because there is no-one left to contradict.

In all such things there are two very distinct essential elements material fact and moral intent. Material facts, one should think, ought to be incontrovertible; and yet, go and see if any two accounts agree. There are facts that remain in eternal litigation. As for moral intent, how is one to find his way, supposing that the narrators are in good faith? And what if they are prompted by bad faith, self-interest and bias? Suppose I have given an order: who can read the bottom of my thoughts, my true intention? And yet everyone will take hold of that order, measure it by his own yardstick, make it bend to conform to his plans, his individual way of thinking And everybody will be so confident of his own version! The lesser mortals will hear it from privileged mouths, and they will be so confident in turn. Then the flood of memoirs, diaries, anecdotes, drawing-room reminiscences; and yet, my friend, that is history.

In spite of his cynical view of history, or perhaps because of it, Napoleon wrote his own history in the form of his memoirs. Not so Wellington, who steadfastly refused to put pen to paper. His take on history, though, was not dissimilar to that of his great rival. In far fewer words than Napoleon, Wellington famously declared that,

The history of a battle is not unlike the history of a ball. Some individuals may recollect all the little events of which the great result is the battle won or lost, but no individual can recollect the order in which, or the exact moment at which, they occurred, which makes all the difference as to their value or importance.

Wellingtons solution to this was, therefore, that only the official accounts of a battle or campaign should be considered:

The duty of the Historian of a battle is to prefer that which has been officially recorded and published by public responsible authorities; next to attend to that which proceeds from Official Authority and to pay least attention to the statements of Private Individuals.

In terms of the Battle of Waterloo, in 1817 Wellington said the following to the British Ambassador to the Netherlands:

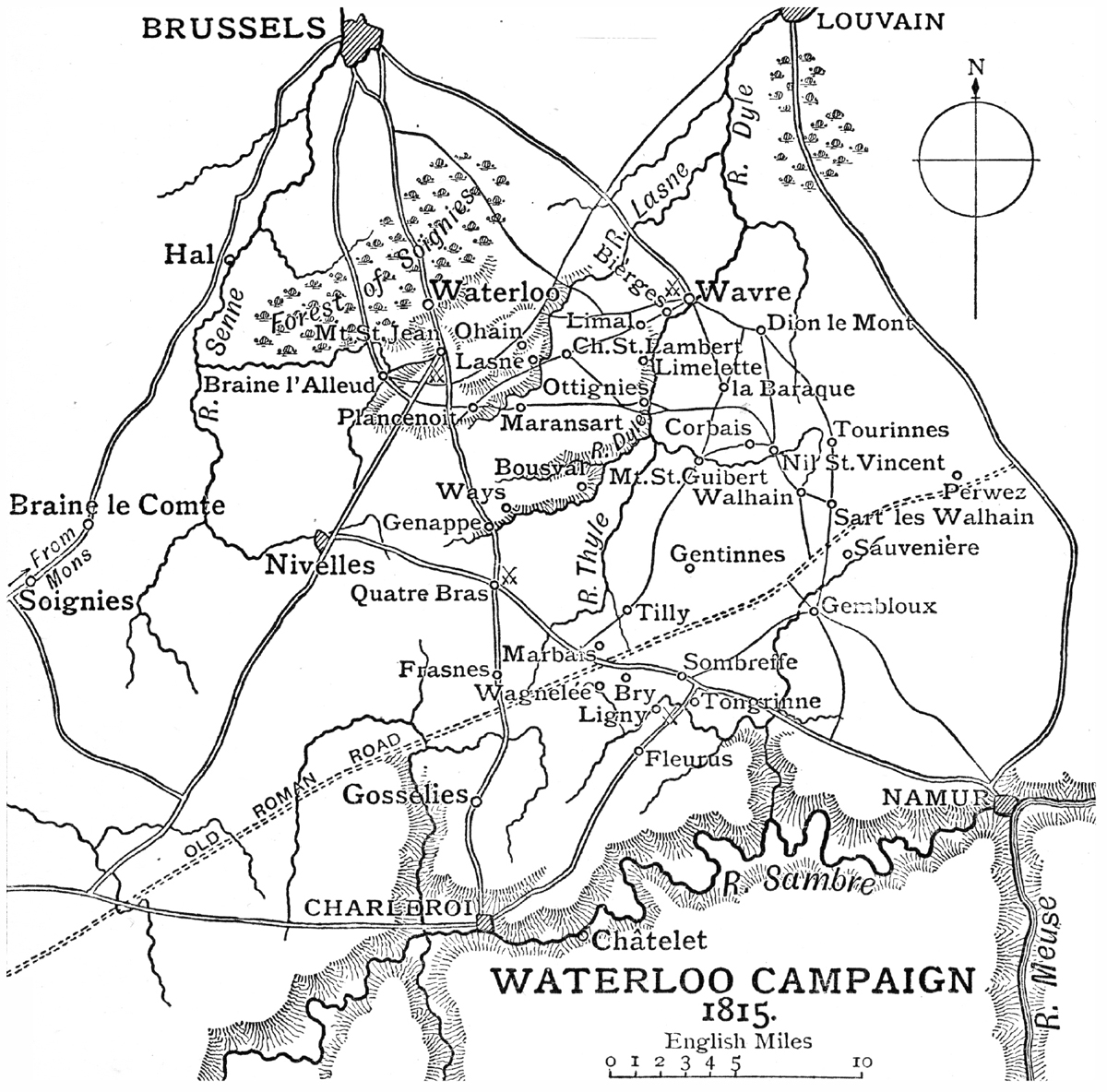

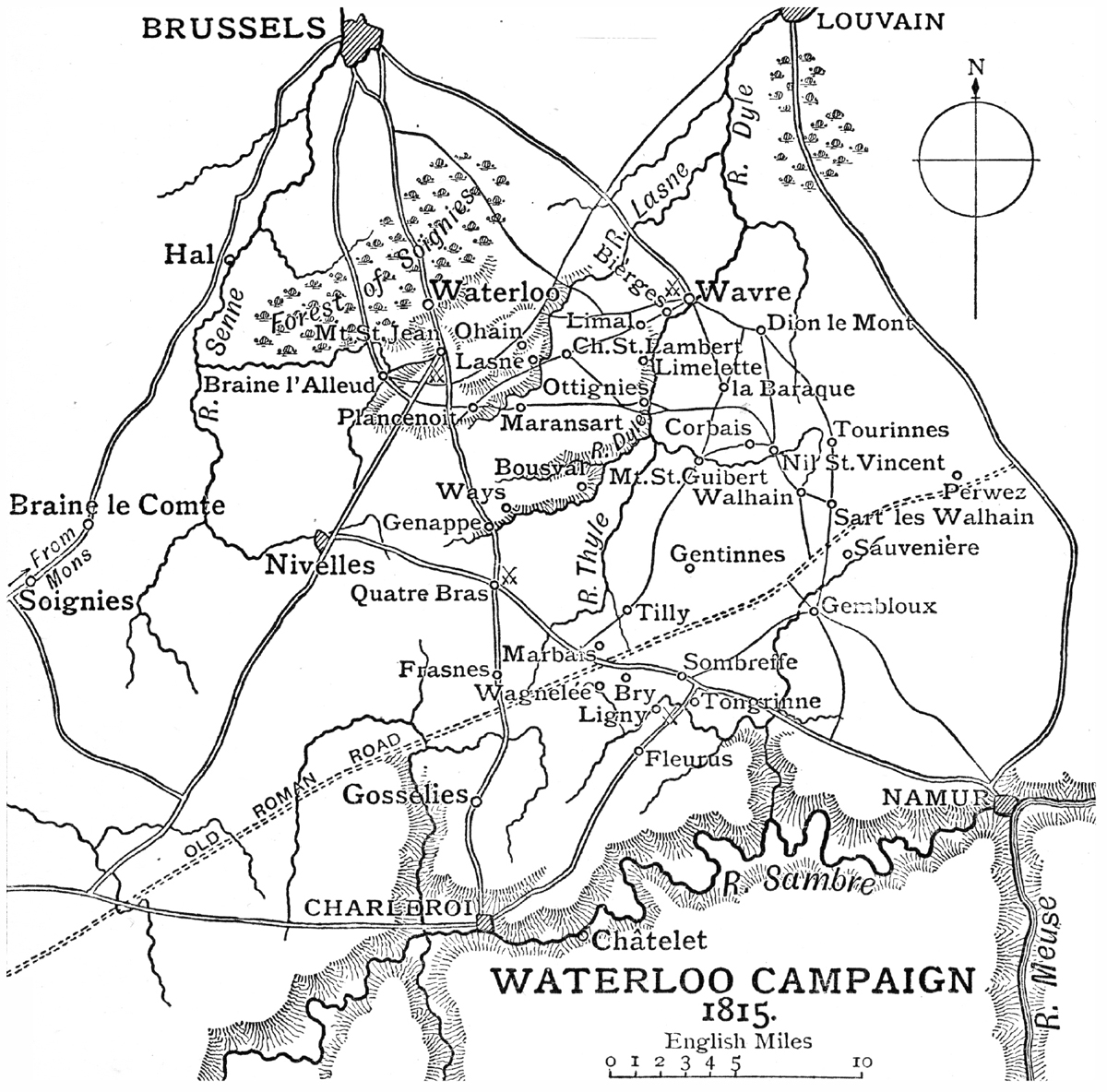

The truth regarding the battle of Waterloo is this: there exists in England an insatiable curiosity upon every subject which has occasioned a mania for travelling and writing. The battle of Waterloo having been fought within reach, every creature who could afford it, travelled to the field; and almost every one who came could write, wrote an account. It is inconceivable the number of lies that were published and circulated in this manner by English travellers; and other nations, seeing how successfully this could be done, thought it as well to adopt the same means of circulating their own stories. This has been done with such industry, that it is now quite certain that I was not present and did not command in the battle of Quatre Bras, and it is very doubtful whether I was present in the battle of Waterloo. It is not easy to dispose of the British army as it is of an individual: but although it is admitted they were present, the brave Belgians, or the brave Prussians, won the battle; neither in histories, pamphlets, plays, nor pictures, are the British troops ever noticed. But I must say that our travellers began this warfare of lying; and we must make up our minds to the consequences.

Wellington was equally contemptuous of the efforts of historians to refight the Battle of Waterloo in print and the Duke, who was twice Commander-in-Chief of the Army let alone twice being Prime Minister, held such an unassailable position in the years after the battle, no-one dare question his opinion. The result was that the official, or Wellingtonian version of the battle, was the only one that could hope to be published. The most egregious example of this is the most highly regarded of all the histories produced during the Dukes lifetime, William Sibornes History of the Waterloo Campaign . This was first published in June 1844, and remained for a very long time the most accurate and detailed history of the campaign. It sold in large numbers and more than 150 years later it is still in print.

The story behind Sibornes book began in 1829 when he was commissioned by the then Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, General Rowland Hill, to create a vast scale model of the Battle of Waterloo which would form the centre-piece of the new United Services Museum in London. Siborne populated his diorama with an astonishing 80,000 model figures representing the British, French and Prussian armies at a ratio of one model to two actual soldiers. Siborne chose to portray one moment in time and he decided upon what was defined as the Crisis of the Battle at around 19.00 hours, as the Imperial Guard reached the crest of the Mont St Jean.

Next page