Michaels Walter Benn. - The Shape of the Signifier

Here you can read online Michaels Walter Benn. - The Shape of the Signifier full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

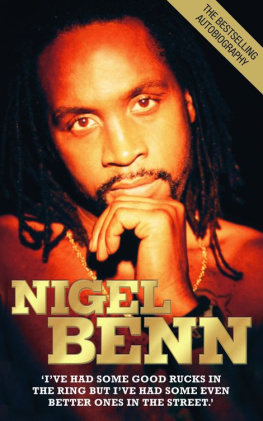

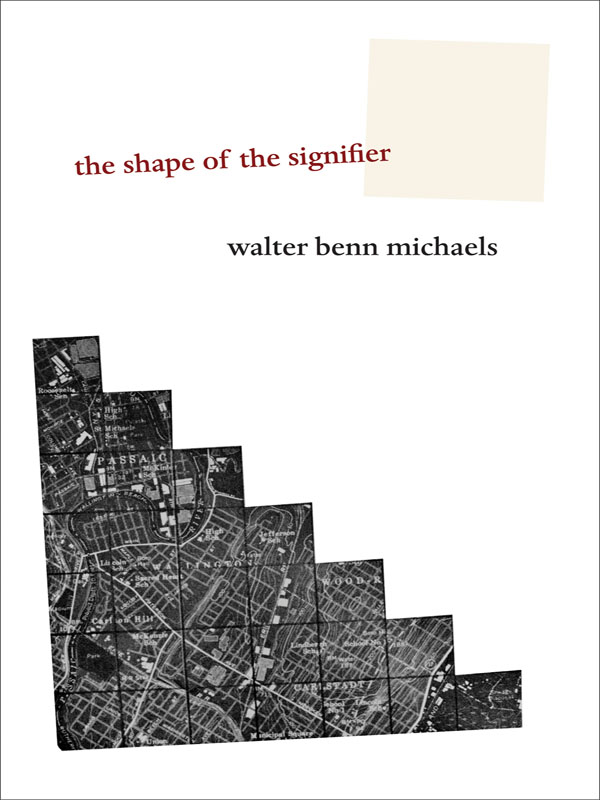

- Book:The Shape of the Signifier

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Shape of the Signifier: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Shape of the Signifier" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Shape of the Signifier — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Shape of the Signifier" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Shape of the Signifier

The Shape of the Signifier

1967 to the End of History

WALTER BENN MICHAELS

Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford

Copyright2004 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Michaels, Walter Benn.

The shape of the signifier : 1967 to the end

of history / Walter Benn Michaels

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-691-11872-8 (alk. paper)

1. American literatureHistory and criticismTheory, etc.

2. American literature20th centuryHistory and criticism.

3. American literature21st centuryHistory and criticism.

4. Signification (Logic) in literature. 5. Literary form. I. Title.

PS25.M53 2004

801.950904dc22 2003055640

British Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Dante

Printed on acid-free paper.

www.pupress.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Acknowledgments

My debt to the work of Frances Ferguson, Stanley Fish, Michael Fried, and Steven Knapp will be obvious to any reader of this book, and I am grateful for the opportunity to acknowledge it here. Michael Fried also read and criticized an earlier version of The Shape of the Signifier, as did Jed Esty, Ruth Leys, Mark Maslan, Sean McCann, and a couple of anonymous readers, and I am grateful for their many helpful suggestions. Even when I could not follow them, I saw their justice. Many others have made important contributions to my thinking about the subjects of this book. I want especially to thank Paul Anderson, Jennifer Ashton, Nicholas Brown, Michael Clune, Jamie Daniel, Winfried Fluck, Jason Gladstone, Reichii Miura, Lisa Siraganian, Martin Stone, and Vershawn Young. Finally, I want to thank the editors of Critical Inquiry, Narrative, New Literary History, Radical History Review, and Transition for permission to reprint material published, in earlier versions, in their journals.

INTRODUCTION

The Blank Page

The Autobiography of the Puritan minister Thomas Shepard, Susan Howe says in The Birth-mark, was originally written in one half of a small leather-bound pocket notebook; if you turn the notebook over and upside down, you find what Howe calls another narrative by the same author, one that she characterizes as more improvisational and that Shepards editors call notes. In between the Autobiography and the notes are eighty-six blank manuscript pages (58). In both the major editions of the Autobiography, selections from the notes are included after the text of the Autobiography proper. Neither editor, Howe says, saw fit to point out the fact that Shepard left two manuscripts in one book separated by many pages and positioned so that to read one you must turn the other upside down (60). Neither editor, of course, included the eighty-six blank pages between the Autobiography and the notes. The reader of the manuscript readsin addition to or as part of the Autobiographyeighty-six pages of empty paper; the reader of either edition does not. Are they reading the same text? Are the eighty-six blank pages part of the text? What do you have to think reading is to think that when you run your eyes over blank pages you are reading them? Or what do you have to think a text is to think that pages without any writing are part of it?

Deleting blank pages isnt by any means the only or the most controversial of the editorial decisions that concern Howe in the essays that make up The Birth-mark, all of which she describes as the direct and indirect results of her encounters with Ralph Franklins facsimile editions of The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson and The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson, encounters which demonstrated to her that what Dickinson wrote had been destroyed rather than reproduced by Thomas Johnsons edition of her poems. Where Howe believes, for example, that the irregular spacing between words and even letters is a part of the meaning of the poems, Johnson regularized the spacing and thus, she thinks, altered the meaning. Examining the facsimiles, Howe came to think of Dickinson as an antinomian in the tradition of Anne Hutchinson. She imagines Dickinsons preference for leaving her poems unpublished as a form of rebellion, an expression of her commitment to a covenant of grace (1), and she imagines the reordering and revision of her manuscripts by Johnson and, to a lesser extent, by Franklin as an expression of their commitment to a covenant of works (2) in which the production of meaning [is] brought under the control of social authority (140). Thus editorial activities like arranging the poems in stanzas and editorial decisions like ignoring stray marks (132) seem to Howe to limit Dickinsons meanings by repress[ing] the physical immediacy (146) of the poems.

But the alignment of Dickinsons meaning with grace rather than works and, even more fundamentally, the commitment to meaning itself can only stand in a somewhat vexed relation to Howes objections to the Johnson edition and to her objections to editorial practice more generally. For The Birth-marks worry about the social control of meaning is complicated by its investment in the physical immediacy of Dickinsons texts, in its investment, that is, in aspects of Dickinsons texts that Howe herself thinks of as meaningless, in the blots and dashes (8) that she calls marks and that she identifies with nonsense (7) and gibberish (2). Its one thing to object to editors who alter the meaning of the text; its not quite the same thing to object to editors who take out blank pages and stray marks, marks that seem to them, and to Howe too, not to have any meaning, to belong rather to what she calls the other of meaning (148). In fact, from this perspective, Howe looks more hostile to antinomianism than Dickinsons editors do, since shes the one defending the letterof the poem, if not the law. But it is also this defense of the literal, not only of the letter but of the smudged letter and not only of the mark but of the space, that leads The Birth-mark into its most original speculations about the ontology of the Dickinson text.

Howes earlier book My Emily Dickinson had made no criticism of the Johnson edition and, without manifesting much interest in its blots and marks, had expressed regret that so few readers would have access to the Franklin facsimile only because it was necessary for a clearer understanding of her writing process. One way to criticize an edition, then, is to criticize it for failing to recognize and reproduce the crucial features, and some of Howes criticisms of Johnson take this form. But her sense of Dickinsons poems as drawings and her commitment to the physical immediacy of them as objects involve a more radical critique, since insofar as the text is made identical to the material object, it ceases to be something that could be edited and thus ceases to be a text at all.

And it is this appearance that the facsimile reproducesthe facsimile shows you what the letters look like and how far apart they are from each other. Its point is not just to convey the meaning of the text to the reader but also to reproduce the experience of its physical features.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Shape of the Signifier»

Look at similar books to The Shape of the Signifier. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Shape of the Signifier and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.