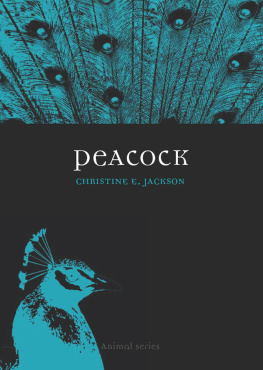

PEACOCK

REVOLUTION

Dress and Fashion Research

Series Editor: Joanne B. Eicher, Regents Professor, University of Minnesota, USA

Advisory Board:

Vandana Bhandari, National Institute of Fashion Technology, India

Steeve Buckridge, Grand Valley State University, USA

Hazel Clark, Parsons The New School of Design New York, USA

Peter McNeil, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

Toby Slade, University of Tokyo, Japan

Bobbie Sumberg, International Museum of Folk Art Santa Fe, USA

Emma Tarlo, Goldsmiths University of London, UK

Lou Taylor, University of Brighton, UK

Karen Tranberg Hansen, Northwestern University, USA

Feng Zhao, The Silk Museum Hangzhou, China

The bold Dress and Fashion Research series is an outlet for high-quality, in-depth scholarly research on previously overlooked topics and new approaches. Showcasing challenging and courageous work on fashion and dress, each book in this interdisciplinary series focusses on a specific theme or area of the world that has been hitherto under-researched, instigating new debates and bringing new information and analysis to the fore. Dedicated to publishing the best research from leading scholars and innovative rising stars, the works will be grounded in fashion studies, history, anthropology, sociology, and gender studies.

ISSN: 20533926

Previously published in the Series:

Moroccan Fashion, Angela M. Jansen

Modern Fashion Traditions, Angela M. Janson and Jennifer Craik (eds)

Fashioning Memory, Heike Jenss

Advertising Menswear, Paul Jobling

Fashioning Identity, Maria Mackinney-Valentin

Islam, Faith, and Fashion, Magdalena Crciun

Inside the Royal Wardrobe, Kate Strasdin

Forthcoming in the Series:

Dressing in Vintage, Nancy Fischer, Kathryn Reiley, and Hayley Bush

Fashioning Brazil, Elizabeth Kutesko

Dedicated to Momone of the many American mothers who endured the Peacock Revolution of the 1960s

CONTENTS

Wool pinstripe vest suit worn by the author in 1970;

knit vest suit in ad by Peters Sportswear, 1970 |

Uncommon shirts in Carriage Club ad, 1969;

machine embroidered shirt in ad by Carriage Club, 1970;

Arrow Shirts ad, 1971;

Romeo shirt with attached fringed scarf by Eros, 1969 |

Hiphuggers in ad by A-1 Pegger, 1966;

bell-bottoms in ad by Cone Mills, 1970;

cuffed baggies in ad by Sutter Mills, 1973 |

Fortrel woven stripe pants in ad by Mr Dee Cee, 1971;

sweater knit coordinates in ad by Wintuk, 1971 |

Open-block lace shirt in ad by Things In General, 1969;

translucent star-studded voile shirt in ad by A-1 Kotzin, 1969 |

Trousers in ad by Seminole Slacks, 1970;

Apache scarves in ad by Dumont Hickok, 1969 |

Wool Nehru jacket by David Peyser and jeweled pendant worn by the author in 1968;

Nehru silk/rayon shirt by Oleg Cassini in ad by Burma Bimas, 1968 |

Eleganza ad, 1972;

Super Fly T.N.T fashions in ad by Blye International, 1973 |

Embroidered shirt with pendant necklace in ad by Gerard Shirts, 1969;

pendants and chain necklaces from various makers worn with Nehru jacket in ad by Man-At-Ease, 1968 |

The Peacock Revolution in menswear of the 1960s came as a profound shock to American society. Young men grew their hair

To the baby boom generation, though, the Peacock Revolution was about more than fashion fads. The radical changes in mens clothing reflected, and contributed to, the changing ideas of masculinity initiated by a youthquake of rebellious baby boomers coming of age in an era of revolutions. New ideas of masculinity emerged from the counterculture of activism that surged across America for civil rights, students rights, womens liberation, gay liberation, Red Power, and Black Power, and against the Vietnam War, the draft, armed occupations of campuses, and the Establishment in general. From these movements came new forms of protest and street dress that altered conventions of masculine identity, ranging from long hair to unisex clothing. Moreover, the peacock dress of baby boomers was a welcomed nontraditional visual identity that was a distinct departure from that of their fathersthe conformist herd of men in gray flannel suits. And rather than concerns about effeminacy in their clothing choices, most youthquake men regarded their peacock shock dress as a personal expression of individuality and modernity. But most important of all, girls were attracted to the sexually confident peacock.

But the Peacock Revolution did not spring into existence suddenly and without warning. To better understand how the Peacock Revolution developed and why it was such a shock to post-Second World War American culture, this study examines many of the socio-economic, sociocultural, and sociopolitical factors that led to the emergence of the youthquake peacock in the early 1960s, and sustained him into the mid-1970s.

Chapter 1 lays out the evolution of the American idea of manhood and masculine identity before 1960. In the early years of the nation, the self-made man was the ideal, replacing the Old World patriarch whose socio-economic power was derived from a hereditary class system. By the late nineteenth century, though, the self-made man encountered challenges that undermined his masculinity. Industrialization and urbanization threatened his individualism and self-determination as an ever-increasing number of men moved to cities and worked for wages. With fathers away at work, their sons were left in the care of women much of the time, inciting a national anxiety about the feminization of future generations of American men. Seeming to validate these fears, medical science discovered a new mental disorder called homosexuality, which confirmed the dangers of a feminized male. In addition, women began to demand equal rights with men, and increasingly entered male domains in the workplace and colleges. By the mid-twentieth century, women had achieved the vote and, during two World Wars, had proven that masses of women could work on an equal footing with men. Consequently, a crisis of masculinity confronted the American male. The established social order of separate spheresmen as patriarchs and breadwinners, women as housewives and mothersseemed to dissolve further with each new generation. Instead, masculinity came to be codified into an orthodoxy of behavior and characteristics, ranging from excellence in sports and with machinery to resisting emasculating influences of women and especially any hint of effeminacy.

Throughout this 150-year evolution of ideas and ideals of manhood, the visual representation of masculinity was short hair and a simple, sober three-piece suit. Even as socio-economic and cultural challenges to masculinity developed over time, the visible self of American men remained fairly constant, with only glacial changes until the development of the sack suit in the 1850s, which then became the standardized uniform of masculine identity for the next hundred years. For post-Second World War fathers, their expectations were that their baby boomer sons would likewise conform to the traditions of masculinity and dress identity that they and their fathers before them had learned and accepted.

Next page