GIBB MEMORIAL TRUST

Published by

The E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any

means including photocopying without prior permission

of the publishers in writing.

First Printed 1954

Reprinted 1969, 1978, 1987, 2008 and 2012

The E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust

ISBN 978 090609 456 3

EPUB ISBN: XXXXXXXXXXXXX

A CIP record of this book is available from the British Library

Further details of the E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust and its publications

are available at the Trusts website

www.gibbtrust.org

This book is available from

Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK

Phone: 01865-241249; Fax 01865-794449

and

The David Brown Book Company

PO Box 511, Oakville, CT 06779, USA

Phone: 860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468

or from our website

oxbowbooks.com

Printed in Great Britain by

Information Press

THIS VOLUME

IS ONE OF A SERIES

PUBLISHED BY THE TRUSTEES OF

THE E. J. W. GIBB MEMORIAL

The funds of this Memorial are derived from the Interest accruing

from a Sum of money given by the late MRS GIBB of Glasgow, to

perpetuate the Memory of her beloved Son

ELIAS JOHN WILKINSON GIBB

and to promote those researches into the History, Literature, Philosophy

and Religion of the Turks, Persians and Arabs, to which, from his

Youth upwards, until his premature and deeply lamented Death in his

forty-fifth year, on December 5, 1901, his life was devoted.

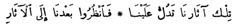

These are our works, these works our souls display;

Behold our works when we have passed away.

VOLUME I

PREFACE

I wish to express my warmest thanks to the Trustees of the Gibb Memorial Fund for making the publication of this work possible, and especially to Professor Sir Hamilton Gibb, who asked me to undertake the work and who has not only read the proofs but has continually given me his interest and encouragement. I am also deeply indebted to Dr. R. Walzer, who has read the proofs, carefully checked the references in my notes, and composed the indexes and the Greek-Arabic and Arabic-Greek vocabularies. I have also to thank Dr. S. M. Stern for his help in completing the subject-index. Finally, I wish to pay a tribute to one who is no longer amongst us, Father Maurice Bouyges, without whose admirable text the work could never have been undertaken.

The marginal numbers in Vol. I refer to the text of Father Bouygess edition of the Tahafut al Tahafut in his Bibliotheca Arabica Scholasticorum, vol. iii, Beyrouth, 1930.

The asterisks indicate different readings from those to be found in Bouygess text: cf. the Appendix, Vol. I, pp. 364 ff.

CONTENTS

TRANSLATION

The denial of a logical necessity between cause and effect

Refutation of the philosophers proof for the immortality of the soul

Concerning the philosophers denial of bodily resurrection

INTRODUCTION

I F it may be said that Santa Maria sopra Minerva is a symbol of our European culture, it should not be forgotten that the mosque also was built on the Greek temple. But whereas in Christian Western theology there was a gradual and indirect infiltration of Greek, and especially Aristotelian ideas, so that it may be said that finally Thomas Aquinas baptized Aristotle, the impact on Islam was sudden, violent, and short. The great conquests by the Arabs took place in the seventh century when the Arabs first came into contact with the Hellenistic world. At that time Hellenistic culture was still alive; Alexandria in Egypt, certain towns in SyriaEdessa for instancewere centres of Hellenistic learning, and in the cloisters of Syria and Mesopotamia not only Theology was studied but Science and Philosophy also were cultivated. In Philosophy Aristotle was still the master of those who know, and especially his logical works as interpreted by the Neoplatonic commentators were studied intensively. But also many Neoplatonic and Neopythagorean writings were still known, and also, very probably, some of the old Stoic concepts and problems were still alive and discussed.

The great period of translation of Greek into Arabic, mostly through the intermediary of Christian Syrians, was between the years 750 and 850, but already before that time there was an impact of Greek ideas on Muhammadan theology. The first speculative theologians in Islam are called Mutazilites (from about A. D . 723), an exact translation of the Greek word (the general name for speculative theologians is Mutakallimun, dialecticians, a name often given in later Greek philosophy to the Stoics). Although they form rather a heterogeneous group of thinkers whose theories are syncretistic, that is taken from different Greek sources with a preponderance of Stoic ideas, they have certain points in common, principally their theory, taken from the Stoics, of the rationality of religion (which is for them identical with Islam), of a lumen naturale which burns in the heart of every man, and the optimistic view of a rational God who has created the best of all possible worlds for the greatest good of man who occupies the central place in the universe. They touch upon certain difficult problems that were perceived by the Greeks. The paradoxes of Zeno concerning movement and the infinite divisibility of space and time hold their attention, and the subtle problem of the status of the non-existent, a problem long neglected in modern philosophy, but revived by the school of Brentano, especially by Meinong, which caused an endless controversy amongst the Stoics, is also much debated by them.

A later generation of theologians, the Asharites, named after Al Ashari, born A. D . 873, are forced by the weight of evidence to admit a certain irrationality in theological concepts, and their philosophical speculations, largely based on Stoicism, are strongly mixed with Sceptical theories. They hold the middle way between the traditionalists who want to forbid all reasoning on religious matters and those who affirm that reason unaided by revelation is capable of attaining religious truths. Since Ghazali founds his attack against the philosophers on Asharite principles, we may consider for a moment some of their theories. The difference between the Asharite and Mutazilite conceptions of God cannot be better expressed than by the following passage which is found twice in Ghazali (in his Golden Means of Dogmatics and his Vivification of Theology) and to which by tradition is ascribed the breach between Al Ashari and the Mutazilites.

Let us imagine a child and a grown-up in Heaven who both died in the True Faith, but the grown-up has a higher place than the child. And the child will ask God, Why did you give that man a higher place? And God will answer, He has done many good works. Then the child will say, Why did you let me die so soon so that I was prevented from doing good? God will answer, I knew that you would grow up a sinner, therefore it was better that you should die a child. Then a cry goes up from the damned in the depths of Hell, Why, O Lord, did you not let us die before we became sinners?

Ghazali adds to this: the imponderable decisions of God cannot be weighed by the scales of reason and Mutazilism.

According to the Asharites, therefore, right and wrong are human concepts and cannot be applied to God. Cui mali nihil est nec esse potest quid huic opus est dilectu bonorum et malorum? is the argument of the Sceptic Carneades expressed by Cicero (

Next page

![Averroes on Platos Republic [trans. Ralph Lerner] (Cornell - Averroes on Plato’s Republic](/uploads/posts/book/324094/thumbs/averroes-on-plato-s-republic-trans-ralph.jpg)