Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

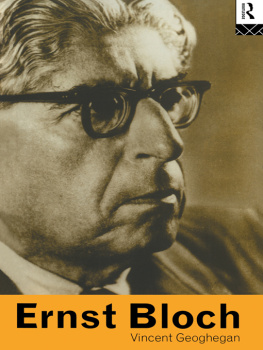

AVICENNA AND THE ARISTOTELIAN LEFT

NEW DIRECTIONS IN CRITICAL THEORY

NEW DIRECTIONS IN CRITICAL THEORY

AMY ALLEN, GENERAL EDITOR

A complete list of titles in the series begins on

AVICENNA AND THE ARISTOTELIAN LEFT

ERNST BLOCH

Translated by Loren Goldman and Peter Thompson

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Avicenna und die aristotelische Linke copyright 1963 Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main

All rights reserved by Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54814-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bloch, Ernst, 18851977, author.

Title: Avicenna and the Aristotelian left / Ernst Bloch ; translated by Loren Goldman and Peter Thompson.

Other titles: Avicenna und die aristotelische Linke. English

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010142 | ISBN 9780231175340 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231175357 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231548144 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Avicenna, 980-1037. | Aristotle. | Materialism.

Classification: LCC B751.Z7 B5613 2018 | DDC 181/.5dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010142

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover art: copyright Shutterstock

CONTENTS

LOREN GOLDMAN

Originally composed for the journal Sinn und Form , Page numbers to the Gesamtausgabe version are noted in square brackets.

Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left comprises a historical monograph on Avicennas legacy and a long appendix entitled Textual Passages and Annotations. The latter, a collection of primary sources along with Blochs commentaries, is integral to the whole. When the book was published, many of these texts were difficult to find, and several remain so: a passage from Brunos The Awakener,

We have aimed for a balance between clarity, readability, and accuracy in capturing Blochs unique voice. Bloch was a notoriously obscure author, whose writing can be fiendishly tricky even for native German speakers as his style combines dialectical logic and poetic expression with a surprising informality. The reader should keep in mind that he does not sound normal to German ears. Given the subject matter, the era, and the subject position of its author, it is no surprise that Bloch occasionally employs Orientalist language that is no longer accepted in academic writing. While nothing here is patently offensive, we have left the text unsanitized; Blochs deep appreciation for the philosophical contributions of Avicenna and his intellectual descendants should be clear. We follow Blochs language throughout, for example, mirroring his use of the names Avicenna and Ibn Sina and preserving his choices of Oriental and Eastern (which he uses neutrally and interchangeably). Central concepts and thorny phrases are given in the notes in the original German. Finally, instead of footnotes, the German text has parenthetical comments, many of which we moved to the notes. To differentiate these from our annotations, Blochs notes are marked in bold .

This edition of Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left would not have been possible without the generosity and expertise of many colleagues. We thank Amy Allen, Osman Balkan, Neil Bernstein, Stephen Bronner, Christopher Buck, Scott Carson, Julie Cooper, Rita Copeland, Mihaela Czobor-Lupp, Eva Del Soldato, Marsha Dutton, Jamal Elias, Ottmar Ette, Matthew Evangelista, Kyle Jones, Ken Garden, Jake Greear, Dimitri Gutas, Andree Hahmann, Gunnar Hindrichs, Martin Jay, Nicole Kaufman, Joseph Lowry, Loren Lybarger, Jon McGinnis, Susan Sauv Meyer, Anne Norton, Johan Siebers, Troels Skadhauge, Steven Tester, Kirk Wetters, Lawrence Wittner, and Slavoj iek. At Columbia University Press, we thank Wendy Lochner, Christine Dunbar, and Lowell Frye. Special thanks, finally, to Frank Degler, Roland Koch, and Klaus Kuhfeld of the Ernst Bloch Center and Archive in Ludwigshafen, Germany, who were wonderfully welcoming during a research visit and gave sage advice at several crucial moments in the translating process. Needless to say, any errors in the text are ours alone.

Loren Goldman

Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left , Ernst Blochs study of the thinker he affectionately called my friend Ibn Sina, Moreover, by situating the worlds emancipatory possibilities in the Islamic interpretation of Aristotle, this small book provides a provocative reconstruction of the sources of modern philosophy that both confounds standard binaries of East/West and Premodernity/Modernity and makes a strong case for the ongoing relevance of metaphysics for contemporary critical theory. For Bloch, the issues raised in this volume resonate far beyond the bounds of scholarship as Avicennas legacy lights a path for inquiry about the very compatibility of utopia and reality. In the works of Avicenna and Averros, thinkers living nearly a millennium before him, Bloch detects the seeds of a lively view of matter that permits and even invites utopian aspiration.

Despite being one of the most consequential German philosophers of the twentieth century, Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left puts paid to this misapprehension, showing Blochs investment in an account of a material reality in which the possibility of radical social transformation grows in the latent tendencies of matter itself.

Blochs utopianism and his interest in aesthetic and religious forms of expression partly explain the relative neglect of his work, but his style admittedly serves as another barrier, for his impressive scope is matched only by the difficulty of his writing. The famously abstruse Adorno wrote an essay entitled Grosse Blochmusik (great Bloch music), a pun on Blechmusik (brass-band music, a title composed with a wink, as Blech can also mean nonsense), and said that The Spirit of Utopia seemed to have been written by Nostradamus himself. Bloch indeed demands an active reader, perhaps because his writing unfolds according to his notion of the basic human condition: the essential darkness of our lived present is illuminated in flashes by the not yet of utopian consciousness. In any event, Adorno, Habermas, and countless others have found the effort of reading Bloch worthwhile.

BLOCHS PHILOSOPHY OF HOPE

Because Blochs general philosophical concerns are hope and utopia, understanding his intellectual project is helpful background for Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left . Schelers and Kracauers quips reflect the perennial suspicion of unreality that confronts utopian thinking. This challenge is, of course, reflected in the word utopia, coined by Thomas More by joining the Greek ( ou : no, not) with ( topos : place), yielding no-place, a convenient homonym of - ( eu-topos ), good-place; Mores narrator, not coincidentally, is named Hytholyday, nonsense-peddler. and the epithet most commonly associated with it was blind.

Bloch does consider hope to be a basic principle of human experience, but he does not suggest its blind embrace or that we hope willy-nilly for anything . Rather than being entranced by realitys mystical shell, Bloch focuses his attention on aesthetics and religion in order to reveal what he believes to be their secular and human inner utopian core, the germ of real longing for what he called the fulfilled moment of genuine emancipation. Because reality is always in the process of becoming, utopian aspiration may have traction and may even aid in the utopias realization. Ultimately, and notably in the closing chapters of The Spirit of Utopia and The Principle of Hope , Bloch attributes realitys processual nature to Marxs basic insight that human labor produces and reproduces the world, thereby (in Blochs reading) identifying free, creative agency as the motor of historical development.