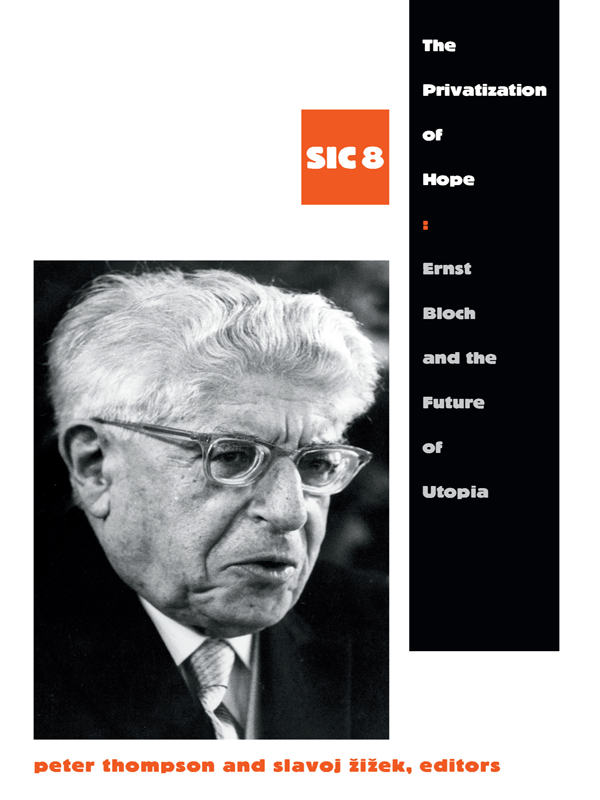

Bloch Ernst - The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia

Here you can read online Bloch Ernst - The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Durham, year: 2013, publisher: Duke University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia

- Author:

- Publisher:Duke University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- City:Durham

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I would first like to thank the contributors to this volume for their patience and for their promptness in responding to queries about their individual chapters. I would also like to thank Creston Davis for his support in the early stages of this project and throughout and for suggesting that I publish this volume in Slavoj iek's SIC series at Duke University Press. Thanks are also due to the British Academy for the three-year Research Development Award made in 2008 which allowed me to start my research on Ernst Bloch and which gave rise to this volume. I would also like to thank Nick Hodgin for his translation work, never an easy job when dealing with Blochian language. I would like to thank my colleagues in the Department of Germanic Studies at the University of Sheffield for their support through difficult times and for the intellectual stimulation provided both by graduate students as well as the research culture in the department.

Above all though, my gratitude is due to Karen Leeder, whose editorial work has been without parallel and indeed has rescued the project at several points. Without her this volume would probably never have appeared.

Wayne Hudson

The odds against a boom in utopia are high.

Jrgen Habermas

Utopia has aged. No one believes anymore in a perfect society or in a perfect humanity. On the other hand, the need to imagine a better future remains. Ernst Bloch was the most original thinker to defend the continuing significance of utopia in the twentieth century, yet he remains relatively little understood in the English-speaking world. When I began to study in Oxford almost forty years ago, I was only allowed to work on Bloch because Leszek Koakowski agreed to supervise. In the early 1970s Gillian Rose and I were among the very few at Oxford trying to rethink Marxism in the light of classical German philosophy. When I wrote The Marxist Philosophy of Ernst Bloch (1982), I had to establish his intellectual credentials and to demonstrate his importance for the Marxist tradition at a time when Althusser and Gramsci were more fashionable figures. In the 1980s German classical philosophy was mainly available in caricature in English, and I did not know enough about Schelling to appreciate Bloch's subtlety at some points. Moreover, although I talked at length with Bloch himself, achievement of the West after the Greeks. Now, as then, however, Bloch's extraordinary legacy has still not been adequately received in the Anglo-Saxon world, despite the labors of many.

In this chapter I draw attention to aspects of Bloch's still largely unrealized legacy and propose that it may be possible to inherit this legacy in the context of a philosophy of the proterior.

I

At his death on 4 August 1977 Bloch was known as a utopian Marxist and as the philosopher of hope, characteristics of declining appeal in the decades that followed. In the English-speaking world, no clear view of Bloch's importance has emerged. Both Anglo-Saxon good sense and the arcane nature of his German texts make it hard for us to know what to make of him. Nonetheless, Bloch's legacy is astonishingly rich, and the volumes of his collected works contain model ideas of outstanding contemporary importance. Today, however, there is a need to release Bloch's legacy from the political as well as the philosophical contexts in which it arose.

In political terms, the hope that Marxism can be salvaged along the lines that Bloch and Lukcs proposed has passed away. It is now widely agreed that a reconstruction of Marxism must be more severe than Bloch realized and may have to conform to intellectual canons to which Bloch himself was not sympathetic. Bloch then easily appears as a utopian who failed to grasp why utopias have to be given up and as a Marxist who lacked the detailed history and economics to provide a powerful framework for Marxist theory. There are those who argue, plausibly within limits, that Bloch belongs to a phase of German Jewish cultural history that is now irretrievably behind us, that Bloch was at best a Marxist Schelling (Habermas), at worst the philosopher of German Expressionism who failed to develop. Equally, there are those who seek to locate Bloch within a typology of western Marxism as a religious leftist who never freed himself from metapolitical satisfactions and who remained politically deluded for most of his career. This is a reading which vulgarizes the complexity of Bloch's political analyses, including his endorsements of Lenin and Stalin, the hard political judgments which he made about the socialist East, and the degree to which he was prepared to tailor his intellectual activities to the attempt to build socialism. It is also a reading which fails to account for the shrewdness of Bloch's analysis of the Nazis, his evaluations of the political potential of a green politics, or Naturpolitik , and his commitment to an alliance of socialist and progressive Christian forces, as well as to the cause of women's liberation and to work for peace.

Because Bloch's work does not conform to the expectations of philosophers of an epistemological bent, he is sometimes presented as a forerunner of postmodernism without the necessary qualifications. However, once it is established that Bloch was not a postmodernist but an advocate of a new edition of the Enlightenment, the relevance of his work on multi-temporalism, non-contemporaneity, and the need to work outside and below tertiary cultures can be discussed.

What is needed is an interpretation of Bloch that refuses safe houses. Bloch was extra muros. He stood outside the university culture of his time and its Neokantian obsessions with epistemological and intra-systematic concerns. He did so as a rebel against the subjection of rational thought to methodologically controlled discourses. The scandalous character of Bloch's work is essential to it, and it is a fundamental mistake to join those who seek to domesticate Bloch posthumously, as though, cleaned up, he could take his rightful place in the German philosophical pantheon alongside Walter Benjamin and Adorno. Like Jakob Boehme or Johann Georg Hamann, Bloch was an irregular, and the importance of his contributions becomes more evident as the limitations of the modern disciplinary organizations of knowledge are recognized.

Against such domestication, it is necessary to insist on the unavailability of Bloch's work , and the fact that there is a continuing delay in the course of its reception as only some aspects of Bloch's work are really taken up.

Bloch's work demands an effort because it is designed to subvert premature conceptions of rationality and the discourses dependent on them. Bloch used a form of abnormal writing as a way of highlighting questions and perspectives that had been missed. He can be seen as a pioneer of a transdisciplinary writing that runs across the disciplines In the Anglophone world, however, those who deny that Nietzsche's contribution to a philosophy of the future has been adequately assimilated by either Heidegger or Derrida will find Bloch contemporary reading. Bloch's work is recondite and full of postponements. To ask, Has the Emperor any clothes? misses its temporal distribution and invites a premature reconstruction of Bloch's ideas. There is no futuristic gnosis (Leszek Kolakowski). Prophecy and predictions are wholly lacking. Nor is occultism the key, Pythagorean or otherwise (George Steiner). Marxist Romantic will not do (Jrgen Habermas). Nor will Jewish messianist suffice (Jrgen Moltmann).

One of Bloch's major insights was that working temporally with the

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia»

Look at similar books to The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Privatization of Hope: Ernst Bloch and the Future of Utopia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.