Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

HOW DID LUBITSCH DO IT?

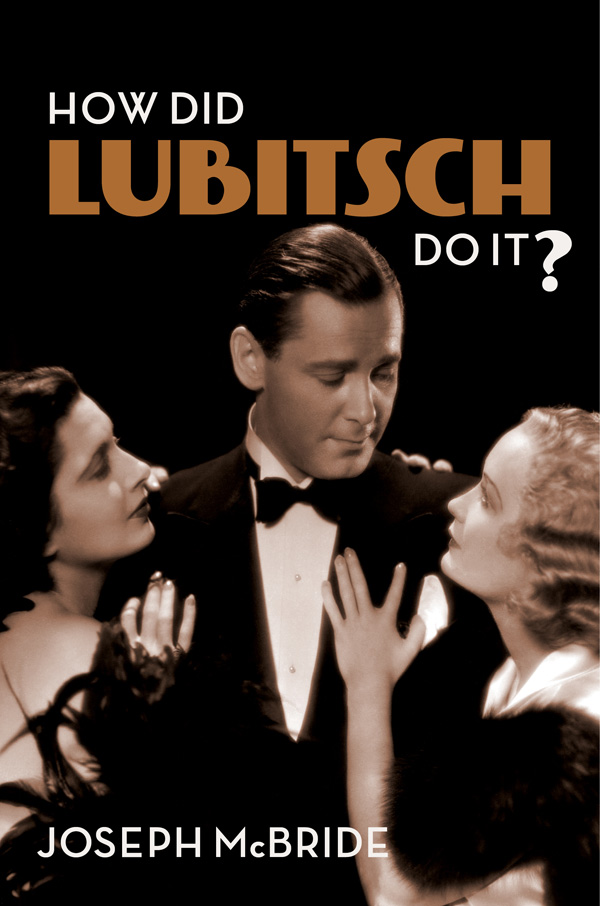

HOW DID

LUBITSCH

DO IT ?

JOSEPH McBRIDE

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS / NEW YORK

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Nicola Lubitsch for quotations from Ernst Lubitschs July 10, 1947, letter to Herman G. Weinberg, which was published in Films in Review (AugustSeptember 1951) and reproduced in Film Culture (Summer 1962), and to the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung for permission to use F. W. Murnaus photograph of Ernst Lubitsch.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Joseph McBride

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54664-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McBride, Joseph, 1947

Title: How did Lubitsch do it? / Joseph McBride.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017044420 | ISBN 9780231186445 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Lubitsch, Ernst, 18921947Criticism and interpretation.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.L83 M37 2018 | DDC 791.4302/33092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017044420

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

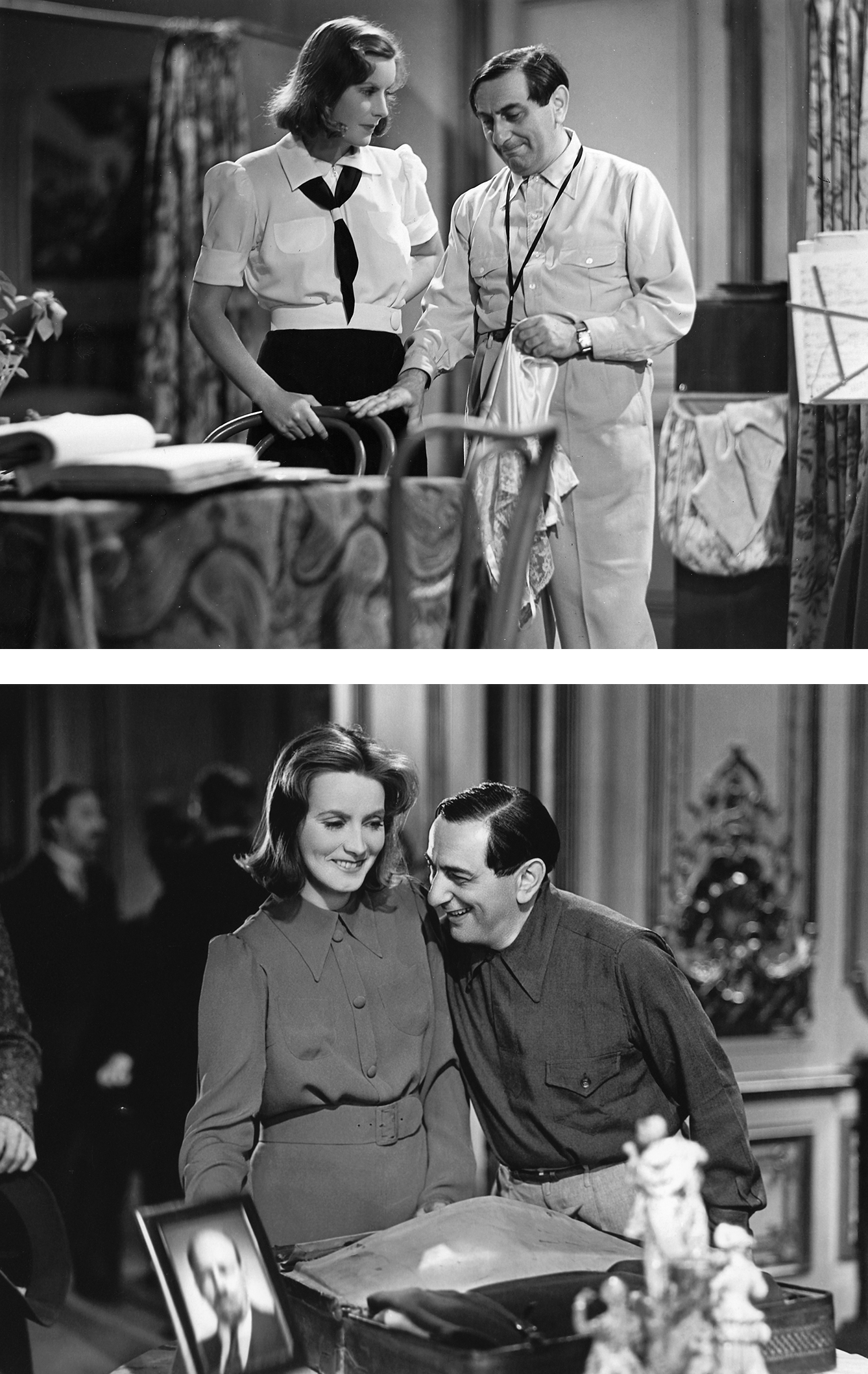

Cover image: Lubitschs 1932 masterpiece, Trouble in Paradise ,

Kay Francis and Miriam Hopkins. (Paramount/Photofest)

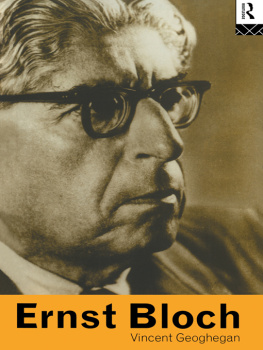

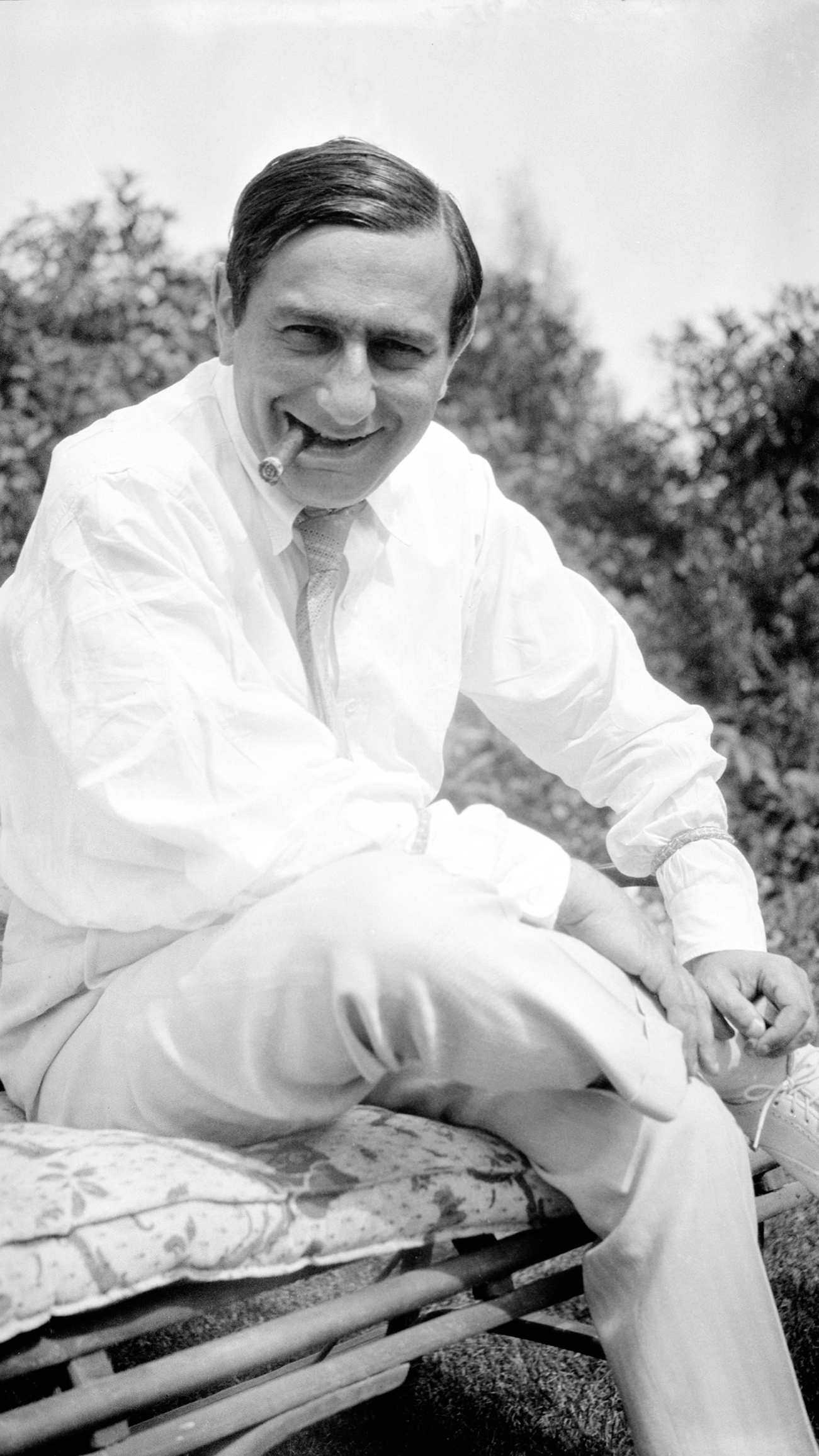

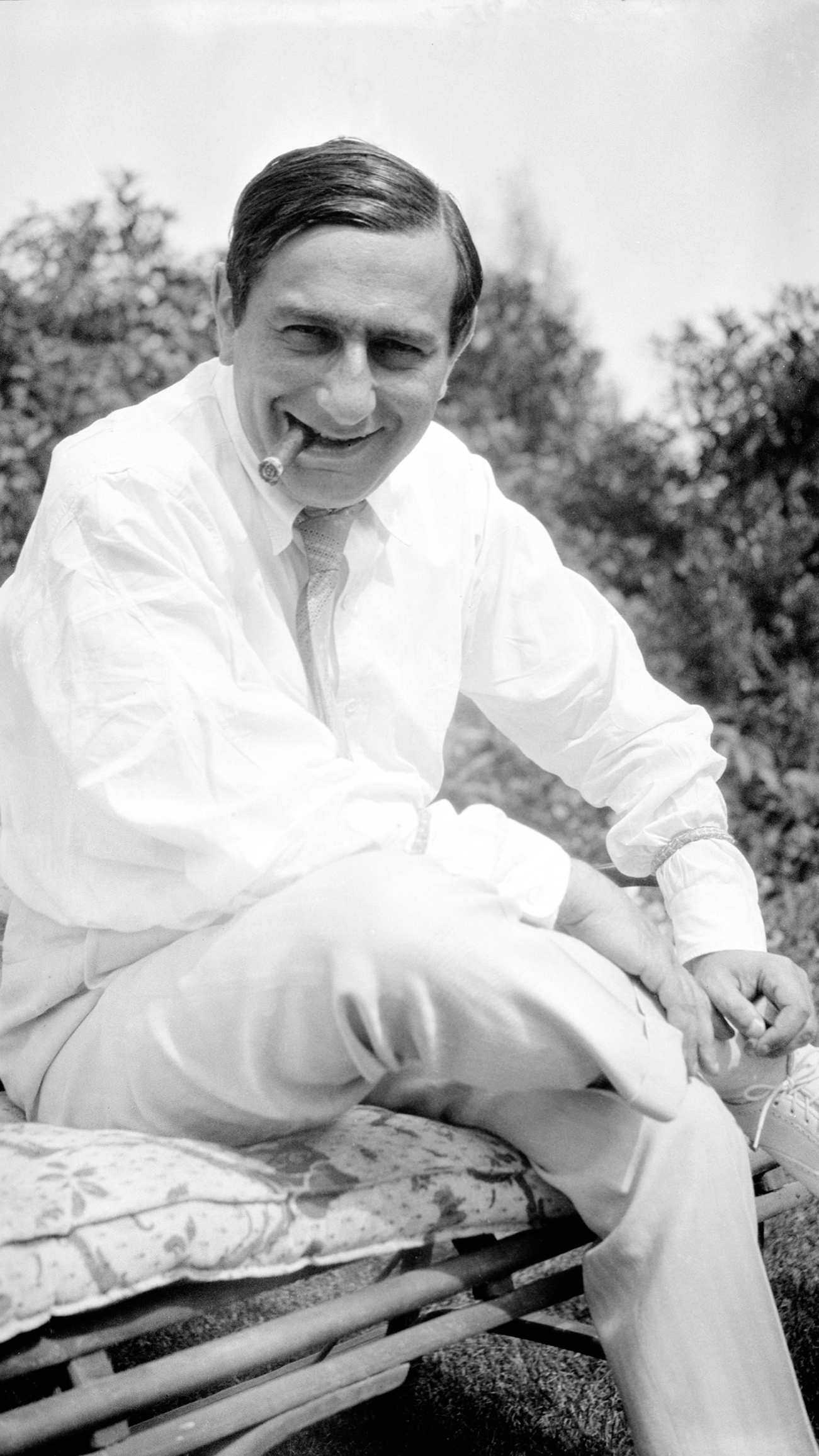

Frontispiece: A portrait of Lubitsch by fellow director F. W. Murnau, taken in Hollywood, ca. 1930. (Courtesy of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung/ Fotoarchiv, Deutsche KinemathekMuseum fr Film und Fernsehen.)

For Ann Weiser Cornell

My love parade in you arrayed

CONTENTS

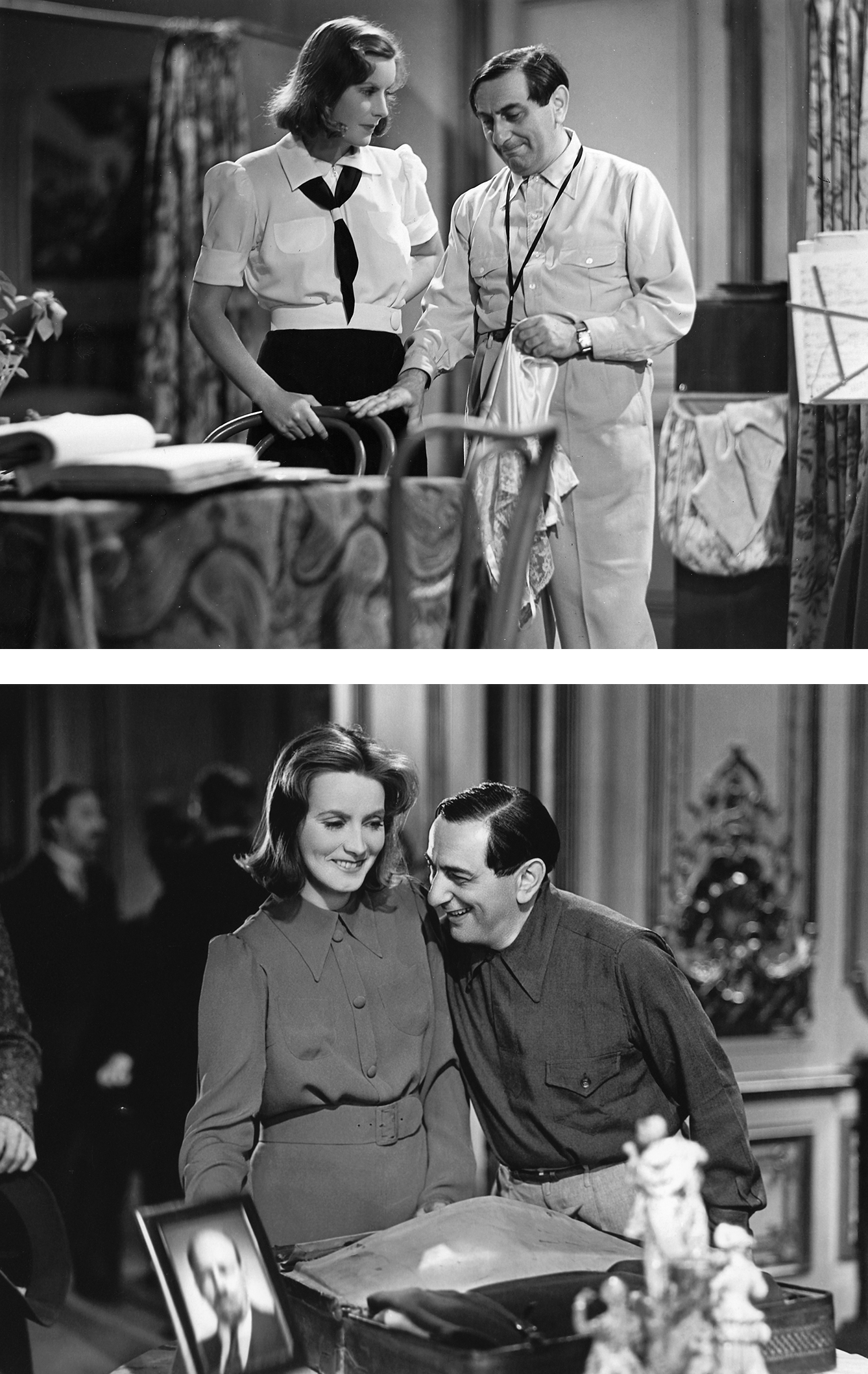

0.1 AND 0.2 Greta Garbo and Lubitsch on the set of Ninotchka (1939). (MGM/From the collections of the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.)

H ow would Lubitsch do it? read the sign on the wall of Billy Wilders modest working writers office on Little Santa Monica Boulevard in Beverly Hills. Saul Steinberg, the New Yorker cartoonist, designed the sign expressly for Wilder. The lettering was elegant old-fashioned cursive, slanted to the right and shaded at its left edge with baroque curlicue. The rectangular gilt frame, with its suggestion of faded elegance, had a modernist shape of roughly Panavision proportions, like the splendid later films Wilder directed while emulating his mentor, including works of varied public reception such as The Apartment , Avanti! , and The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Lighting a cigarin another homage to Lubitsch, who was rarely found without his UpmannWilder told an interviewer in 1989, I made that sign. That way I never allow myself to write one sentence that I would be ashamed to show to my great friend, Ernst Lubitsch.

The director of supremely stylish classics including Trouble in Paradise , Ninotchka , and The Shop Around the Corner , Lubitsch was revered in his day by such other leading filmmakers as Orson Welles, Jean Renoir, Max Ophls, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and Preston Sturges. In the words of one of his actors, David Niven, Lubitsch was the masters master. Renoir, another great European migr director, went so far as to say of Lubitsch, He invented the modern Hollywood. Welles declared in 1964 that Lubitsch is a giant. Lubitschs talent and originality are stupefying. Yet today Lubitsch is no longer the familiar name to moviegoers that he once was. What happened?

Lubitsch (18921947), a native of Berlin, was imported from Germany to Hollywood by Mary Pickford in 1922. In Germany he had become known as the D. W. Griffith of Europe because of his flair for making large-scale historical spectacles but with a refreshingly modern approach to sexuality, including Carmen ( Gypsy Blood ), Madame DuBarry ( Passion ), Anna Boleyn ( Deception ), and Das Weib des Pharao ( The Wife of Pharaoh ) . But before creating those spectacles, Lubitsch had first made his name with raucous comedies of increasing sophistication and stylization, such as Ich mchte kein Mann sein ( I Dont Want to Be a Man ), Die Austernprinzessin ( The Oyster Princess ), and Die Puppe ( The Doll ) . Not long after his arrival in Hollywood, Lubitsch somewhat surprisingly abandoned the spectacle genre. He made the workmanlike Rosita (1923) with Pickford in that vein but then mostly left the genre for Cecil B. DeMille and others to mine with lesser skill. Instead, with astonishing swiftness in the silent era, Lubitsch set the tone for obliquely suggestive filmmaking in Hollywood with his subtle and influential 1924 dramatic comedy The Marriage Circle .

Lubitsch became Hollywoods most acute commentator on sexual mores, countering American puritanical hypocrisy with European sophistication, and making his adopted countrymen enjoy it. His audacity became more elaborate and subtly stylized in his romantic comedies of the early sound years; sound enabled him to add new layers of depth in exploring the differences between what people say and what they mean. Lubitsch virtually created the romantic comedy genre in both Germany and the United States and brought it to perfection with his cleverly risqu yet touchingly tender masterpiece of and about the Depression era, Trouble in Paradise (1932) . His other masterworks in that genre include Lady Windermeres Fan , Design for Living , The Shop Around the Corner , and Heaven Can Wait. If those were not enough to ensure his cinematic immortality, Lubitschs bawdy pre-Code musicals such as The Love Parade , Monte Carlo , The Smiling Lieutenant , and The Merry Widow helped invent the musical genre as an integrated form for comical and dramatic exploration of character rather than as a mere framework for disconnected songs and dances.

Lubitschs work seems timeless because it is so deeply a projection of his imagination, a Platonic ideal of a world that vanished around the time he started making his films; his on-screen version is a more gracious, more elegant world than any that had actually existed. The fact that it was also a world from which Lubitsch himself would have been mostly excluded adds a level of ironic poignancy to his work that helps make it so complex. Lubitsch kept alive some of the more appealing traditions of the old, vanished milieu, viewing imperial pomp with satirical amusement and doing so from the distant geographical outpost of Hollywood studios even while his native land was descending into chaos. An essentially rootless man outside his empire of the studio lot, Lubitsch found his bearingsof necessity, but also by preferencein the artifice of motion pictures. Through his eyes, we can live vicariously in that artificial, largely imaginary world he created and which he made so much more alluring than the messy world outside the movie palaces of his time or the video screens of our day.