To my dear Karola Piotrkowska

First published as Erbschaft dieser Zeit

Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1962

This English translation Polity Press 1991.

First published 1991 by Polity Press

in association with Basil Blackwell

Editorial office:

Polity Press, 65 Bridge Street,

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Marketing and production:

Basil Blackwell Ltd

108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent

ISBN 0745605532

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

TRANSLATORSINTRODUCTION

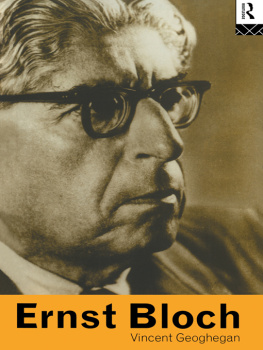

The first edition of Erbschaft dieser Zeit was published in Zurich in 1935, during Ernst Blochs five-year period of emigration from Nazi Germany in various European capitals before his final emigration to America for ten years in 1938. The book thus appeared roughly halfway between the publication of the first edition of Blochs major literary work Spuren (Traces) in 1930 and the beginning of his herculean labours, covering almost the whole of his period of American exile (193849), on the vast three-volume work that was to form the keystone of his philosophy, Das Prinzip Hoffnung (the English version of which by the present translators with Paul Knight was published as The Principle of Hope by Basil Blackwell in 1986). The structure of the book reflects a further development of the open pattern of short, often challengingly cryptic and intensely poetic texts employed in Spuren, while also prefiguring in the brief preliminary section Der Staub (Dust) and each of the subsequent three major parts the structural progression used in The Principle of Hope from these densely evocative introductory passages towards longer stretches of direct cultural, social and political analysis. Erbschaft dieser Zeit, which sets out to explore the true legacies of our present age of transition, thus itself also plays a crucial transitional role in the structural and philosophical development of Blochs work as a whole, culminating in his wider theory of the world as open process and the concept of the Not-Yet-Conscious, the preconscious dimension in past, present and future, at the heart of his comprehensive philosophy of hope.

The bulk of the book was written in the early 1930s, although the oldest sections go back as early as 1924 (all dates given in the text are those of the original versions of the respective pieces). The enlarged and revised edition translated here, most notably incorporating the essays that formed Blochs central contribution to the literary controversy in the late 1930s that has come to be known as the Expressionism debate, was published in Frankfurt in 1962, shortly after Bloch had decided to remain in the West, after the erection of the Berlin Wall, and to accept a guest professorship at Tubingen university. Blochs bitter disappointment with socialist developments in East Germany, where he had been obliged to retire from academic life, is clearly apparent in his 1962 Postscript to the Preface to the first edition of the book, expressing an open disillusionment with the narrow totalitarian system he had just escaped (particularly with its official cultural policy of socialist realism), which belies the superficial right-wing caricature of Bloch as a blinkered apologist for Marxist orthodoxy.

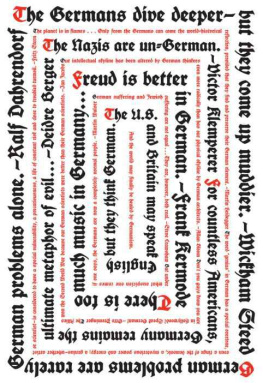

It was precisely against the dogmatic advocates of socialist realism that Bloch made his courageous stand in defence of the artistic avantgarde in the vehement debate in the 1930s concerning the relative merits of Expressionism and realism. His particular adversary was the Hungarian literary critic Georg Lukcs, one of his closest friends in younger days, who had sought to trace a direct link between Expressionism and National Socialism in his essay Gre und Verfall des Expressionismus (Greatness and Decline of Expressionism), first published in an issue of Internationale Literatur in Moscow in 1934. But the Expressionism debate proper did not get under way until over three years later, sparked off by two essays in the September 1937 number of the literary magazine Das Wort, a major organ of the Volksfront (a popular front of intellectuals of various political persuasions, united in their opposition to fascism). The first of these essays comprised an attack by Klaus Mann on the Expressionist poet Gottfried Benns complicity with National Socialism, and the second, by the hard-line functionary Alfred Kurella (under the pseudonym of Bernhard Ziegler), also employed the example of Benn to support the thesis that Expressionism was a logical precursor of fascism. Other writers and artists were quick to spring to the defence of Expressionism by pointing out the tremendous political diversity of its major exponents, and the consequent absurdity of condemning the movement lock, stock and barrel as a homogeneous enterprise. There was indeed a strongly progressive, implicitly anti-fascist strain in the best Expressionist writing and art, dwarfing the work of a writer like Benn writers of the calibre of Johannes R. Becher, Georg Heym, Else Lasker-Schuler or Ernst Toller, to name just a few.

Bloch himself had been an active exponent of this progressive vein of Expressionism in his first philosophical work Geist der Utopie (The Spirit of Utopia) published in 1918, so his subsequent defence of the movement was sharpened by an element of direct personal and political commitment. His first major contribution to the Expressionism debate was the article Diskussionen ber Expressionismus, first published in Das Wort in 1938 and later revised for inclusion in the enlarged edition of Erbschaft dieser Zeit. As a glaring topical example of the antipathy between Expressionism and fascism, Bloch could point to the Nazi exhibition of Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art), containing works by almost all the great Expressionist artists, which opened in Munich in the summer of 1937 and which Bloch had already pilloried in the slightly earlier essays Der Expressionismus, jetzt erblickt (Expressionism, seen now) and Gauklerfest unterm Galgen (Jugglers Fair beneath the Gallows), both also later incorporated at different points into the enlarged edition of the present book. Coincidentally, this exhibition was organized by the would-be artist, Hitlers crony and President of the Reich Chamber of Art, Adolf Ziegler, his surname ironically identical with that of the time-serving Communist anti-Expressionist Kurellas adopted pseudonym. This chance echo highlights the fact that deepseated cultural philistinism was not the exclusive preserve of the right at that time. Stalins cultural Gleichschaltung (bringing into line) had been effected, and the truly revolutionary legacies of Russian Expressionism and Constructivism had already been sacrificed to sterile socialist realist conformity. And naturally this line was dogmatically followed by Communist parties all over Europe. It may indeed even be argued that the convergence of the artistic policies of right and left at this time irrevocably halted the development of a genuine revolutionary aesthetic in Europe.