Author:

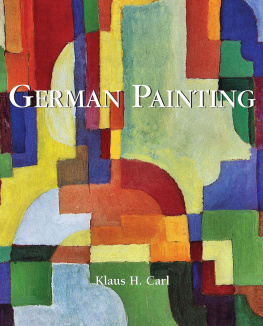

Klaus H. Carl

With detailed text citations from:

Dr Dorothea Eimert, Art and Architecture of the 20thCentury

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-bar www.image-bar.com

Erich Heckel Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Karl Schmidt-Rottluff Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Max Pechstein Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Gabriele Mnter Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Heinrich Nauen Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Paul Klee Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Max Ernst Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

George Grosz Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Otto Dix Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Conrad Felix Mller Estate, Artists Right Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-793-3

Klaus H. Carl

GERMAN PAINTING

FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO NEW OBJECTIVITY

Contents

Christ in Majesty, 1120. Fresco.

Apse, Church of Sts Peter and Paul,

Reichenau-Niederzell.

Art of the Middle Ages

From the Beginning to the Romanesque

When the Romans conquered most of the country north of the Alps, previously inhabited by Germanic tribes, built fortified camps for their troops, and founded colonies which frequently evolved to cities to secure their reign, they did not meet any noticeable resistance against the introduction of their culture. The art of construction and sculpture was unknown to the Germanic people, even in their original forms. It is even likely that they felt that as warriors this refined cultural practice of art was unworthy.

Only when the Romans began to build bathrooms and buildings, shelters, road systems, water lines, and other things, the attitude of the Germans may have gradually changed. More and more they exercised the advantages given to them by the foreign culture of the conquerors, which they initially rejected. It was then likely that the impulse of imitation would soon awaken among them. The Romans felt so sure of their property that they would build magnificent country houses, in particular on the banks of the Rhine and its tributaries, which they decorated with the usual artistic decor of their native soil, especially with sculptures and mosaics.

However, the artists who had followed the conquering armies did not progress beyond a modest degree of technical ability, which became noticeable as the demand for works of art in the Roman settlements increased. Most often the sculptors were engaged in the creation of a great number of grave monuments and gravestones which still remain today. From this it can be deduced that the artists mainly stuck to down-to-earth, concrete reproductions, creating portraits of the dead in rough, realistic ways without any artistic refinement.

The contact with Rome gradually broke off. But even without this distance, Roman art would not have flourished on the Germanic soil without more new blood, as the ancient art had become, even in Rome, unimaginative and homespun. However, this austere, realist art may have developed nonetheless in the new homeland, had the storms of tribal migration not destroyed the Roman Empire and at the same time the Roman culture.

When new states emerged out of the chaos and withstood the test of time, taking care of the art was probably the last concern of the respective ruler, and if they did care about it, then it was an art that first benefited them. It satisfied their love of splendour and their need to keep servants, warriors, and vassals happy through generous gifts.

From grave finds, we have some evidence about the original Germanic practice of art. In particular, numerous clips, clothes pins, belt fittings, necklaces and hair jewellery of gold, silver, and other metals have been found in Frankish graves dating to around the 3 rd to the 8 th century. Even though they take their inspiration from Roman models, they show independent jewellery ornamentation, a wonderful play of tangled lines and braided, interwoven bands, ending in grotesque human and animal heads. This ornamentation has by no means disappeared from the formal repertoire of the Germanic people and would later emerge once more in the Romanesque art of the Middle Ages.

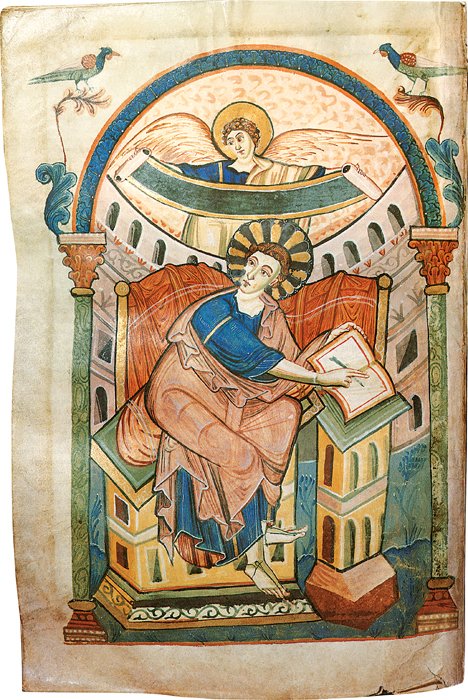

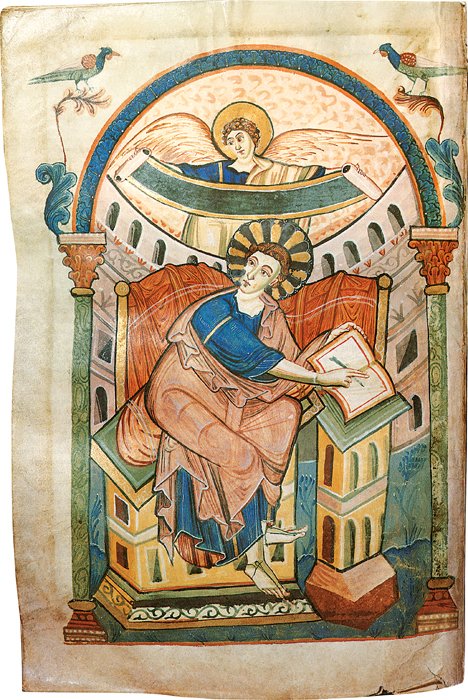

Although the Merovingian rulers completed extensive activity in church-building, none of their buildings have been preserved. From written records it is known, however, that their churches were based on early Christian basilicas and usually had cruciform shapes. The national element of art was represented at that time by miniature painting only, brought by the first preachers of the gospel in north-western Germany: Irish and Scottish monks.

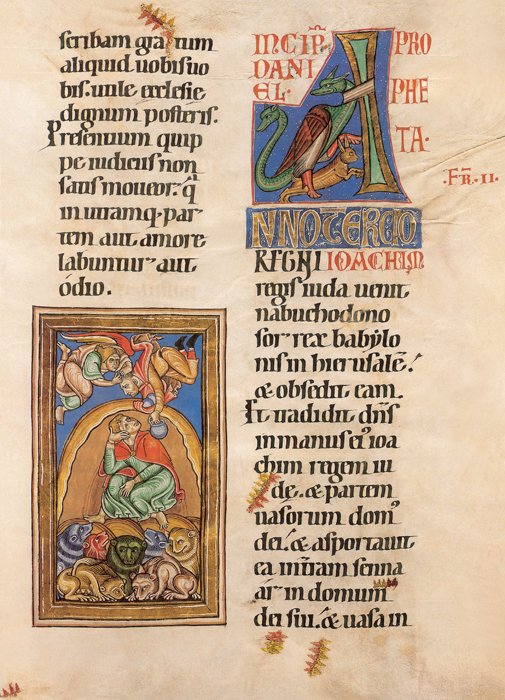

In contrast to the Byzantine illuminated manuscripts, where the emphasis was placed on the illustrations not text, the Irish monks aspired to develop writing artistically. They carried it out with the utmost cleanliness and neatness, allowing the development of the calligraphy, to which they added rich adornments of ornate initials, borders, border decorations, and other decors. Without foreign influences, they brought along their own unique, ornamental style, which was so closely related to the ancient Germanic ornamentation in its basic forms, especially in the strong disposition for splendour and in the inexhaustible variety of play with grotesque animal forms, that it found understanding and willing reception.

This calligraphic feature of the miniature painting was applied by the Irish monks, whose manuscripts were spread all over Germany up to the Swiss town of St Gallen, and thus influenced the art of the 7 th and 8 th centuries significantly. The latter finally lost all connection to nature and could therefore not serve as a model for the Frankish and Anglo-Saxon scribes who had already progressed much more in the depiction of the human form, though still standing under the influence of the after-effects of their idols of ancient art. Most likely, the Irish ornamentation had been adapted by them, and even enhanced.

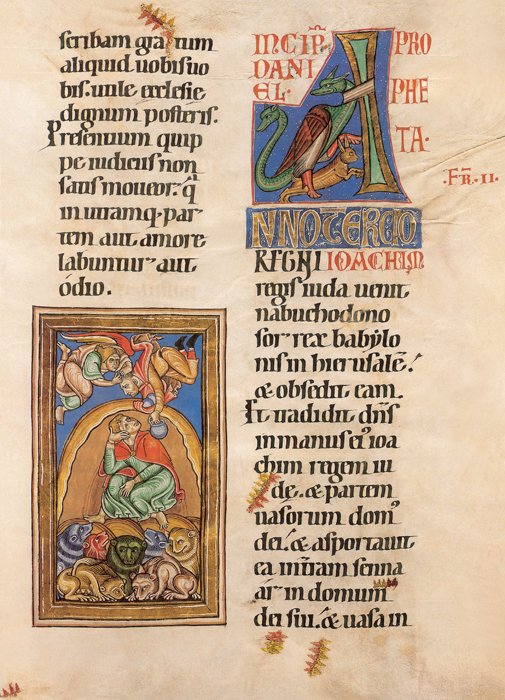

Initial page of the Book of Daniel:Daniel in the Lions Den,

folio 105 (recto), Major Prophets, Old Testament,

Latin Bible, Swabia (Weingarten), c. 1220.

Parchment, 479 x cm (text 335 x cm ).

Next page