Rocket and Lightship

Essays on Literature and Ideas

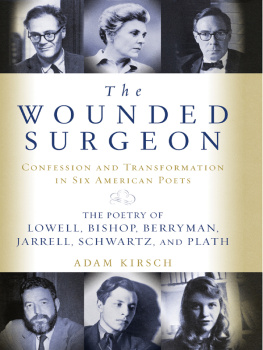

Adam Kirsch

For Remy

Contents

The Importance of Being Earnest: David Foster Wallace

I t is important, therefore, to hold fast to this: that poetry is at bottom a criticism of life. Matthew Arnolds formulation, which he advanced in his essay on Wordsworth and returned to in later essays, has never quite recovered from the beating it took at the hands of T. S. Eliot, who found it a shallow way of thinking about something as fundamentally mysterious as poetry. At bottom, that is a great way down; the bottom is the bottom. At the bottom of the abyss is what few ever see, and what those cannot bear to look at for long; and it is not a criticism of life, Eliot replied. Indeed, it is hard to be quite comfortable with the way Arnold goes on to define the criticism of life as the powerful and beautiful application of ideas to life. Application sounds like too external and mechanical a process, and not all the ideas we need are beautiful.

To understand the phrase more broadly, however, may redeem it. All literature, not just poetry, is a criticism of lifebut not in the sense of a negative comment or a suggestion for improvement, as Arnold seems to imply. Such criticism is, rather, the record of one minds response to the experience of being in the world. Each genre of literature has its own methods for representing that experience and interpreting it: poetry uses rhythm and metaphor, fiction uses plot and character. In a broader sense, even genres of writing that are not ordinarily thought of as literarysuch as theory, philosophy, politics, historycan also be seen as criticisms of life. For any kind of serious writing is expressive of the writers experience of being in the world, of his aspirations and expectations and anxieties.

If this is so, then almost any genre of writing can be usefully subjected to literary criticism. For criticism, too, is a kind of literature; the critic expresses his own sense of life through his responses to other minds and sensibilities. This makes criticism, inevitably, a less immediate and powerful form of writing than poetry or fiction, and a more self-conscious one. But since all serious readers engage in this same process of shaping themselves in response to what they read, criticism is also capable of a unique kind of intimacy, and even, despite appearances, vulnerability. For the critics assertions are always, read truly, only propositions, impressions, requests for assent. This is how it seems to me: does it seem that way to you too?

Thinking of my own work as a critic in this way, I see a basic continuity between writing about poetry, as I have done in the past, and writing more broadly about literature and ideas, as I do in this book. These essays, written over approximately the last eight years, engage with texts at the point where literature intersects with society and historythe point where, I think, criticism eventually has to end up. Begin thinking about, say, the novels of E. M. Forster, and soon enough it becomes clear that Forsters fiction is born from, and limited by, a certain understanding of liberalism. Thinking about Darwinism means wondering what the animalization of humanity means for art and ethics. Examining a writers Jewishness, as I do in several essays, means exploring his or her most personal being and most public, historical identity.

This way of thinking about criticism rests on the liberal principle that the individual, the individuals experience of life, is prior to all the languages we use to describe it. Different kinds of writing demand different techniques of response, but in every case what interests me is the criticism of life a text expresses. And the way that certain themes and concerns keep coming back from essay to essay in this book suggests that I have tried, at times unconsciously, to express something of my own experience in the form of criticism.

Rocket and Lightship

I n his early story Tonio Krger, Thomas Mann created a parable of one of the central modern beliefs, which is that the artist is unfit for life. Starting from childhood, everything about Tonio serves to mark him out from the society in which he is fated to live. Dark among blonds, half-Spanish among Germans, an introvert among the sociableall these are merely symbols of his true estrangement, which is that he is a writer. But his pride in the depth of his feeling and understanding is inseparable from his longing for, and envy of, the ordinary, which is embodied in his boyhood friend Hans Hansen and his teenage love Ingeborg Holmneither of whom reciprocate or even notice his passion. At the end of the story, Tonio has a vision of these two paired off in happy, fruitful partnershipa destiny he can never share: To be like you! To begin again, to grow up like you, regular like you, simple and normal and cheerful, in conformity and understanding with God and man, beloved of the innocent and happy. But love and marriage and parenthood are barred to Tonio, because he has an artists soul: For some go of necessity astray, because for them there is no such thing as a right path.

In associating art with loneliness, sorrow, and death, Mann was not presenting a new idea but perfecting an old tradition. Everywhere you look in the art and literature and music of the nineteenth century, you find examples of this same figure, the artist banished from life: in Leopardi, the stunted, ugly, miserable poet; in Flaubert, the novelist too fastidious for bourgeois existence; in Nietzsche, the wanderer upon the earth. What is different about Mann is that, writing in 1903, he has fully assimilated the Darwinian revolution, which taught him to think about life in terms of survival and fitness. In his great novel Buddenbrooks , Mann tells the story of a family whose fitness to thrive in modern society declines in tandem with the growth of its interest in ideas and art. Its last representative, Hanno, is a musical prodigy who dies an excruciating death before reaching sexual maturity.

Manns sense of the perverse glory of the artists unfitness is one of his legacies from Nietzsche, who wrote in Human, All Too Human , under the rubric Art dangerous for the artist, about the inability of the artist to flourish in a modern, scientific age:

When art seizes an individual powerfully, it draws him back to the views of those times when art flowered most vigorously.... The artist comes more and more to revere sudden excitements, believes in gods and demons, imbues nature with a soul, hates science, becomes unchangeable in his moods like the men of antiquity, and desires the overthrow of all conditions that are not favorable to art.... Thus between him and the other men of his period who are the same age a vehement antagonism is finally generated, and a sad endjust as, according to the tales of the ancients, both Homer and Aeschylus finally lived and died in melancholy.

As Nietzsches reference to the Greeks suggests, the link between artistry and suffering is not a modern invention. What is modern is the sense of the superiority of the artists inferiority, which is only possible when the artist and the intellectual come to see the values of ordinary lifeprosperity, family, happinessas inherently contemptible. The exhilarating assault on bourgeois values that was modernism, in all the arts and in politics too, rested on the assumption, nurtured through the nineteenth century, that there was nothing enviable about what T. S. Eliot bitterly derided as the cycle of birth, copulation and death. Art, according to a modern understanding that has not wholly vanished today, is meant to be a criticism of life, especially of life in a materialist, positivist civilization such as our own. If this means that the artist cannot share in civilizations boons, then his suffering will be a badge of honor. (Dictators who sought to protect their people from the infection of degenerate art were paying a twisted homage to this principle.)

Next page