Natural Selection

And Tropical Nature

Essays On Descriptive And Theoretical Biology

BY

ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE

NEW EDITION WITH CORRECTIONS AND ADDITIONS

1895

Copyright 2016 Read Books Ltd.

This book is copyright and may not be

reproduced or copied in any way without

the express permission of the publisher in writing

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

I

IV

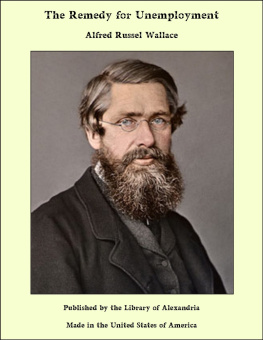

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace was born on 8th January 1823 in the village of Llanbadoc, in Monmouthshire, Wales.

At the age of five, Wallaces family moved to Hertford where he later enrolled at Hertford Grammar School. He was educated there until financial difficulties forced his family to withdraw him in 1836. He then boarded with his older brother John before becoming an apprentice to his eldest brother, William, a surveyor. He worked for William for six years until the business declined due to difficult economic conditions.

After a brief period of unemployment, he was hired as a master at the Collegiate School in Leicester to teach drawing, map-making, and surveying. During this time he met the entomologist Henry Bates who inspired Wallace to begin collecting insects. He and bates continued exchanging letters after Wallace left teaching to pursue his surveying career. They corresponded on prominent works of the time such as Charles Darwins The Voyage of the Beagle (1839) and Robert Chambers Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844).

Wallace was inspired by the travelling naturalists of the day and decided to begin his exploration career collecting specimens in the Amazon rainforest. He explored the Rio Negra for four years, making notes on the peoples and languages he encountered as well as the geography, flora, and fauna. On his return voyage his ship, Helen, caught fire and he and the crew were stranded for ten days before being picked up by the Jordeson, a brig travelling from Cuba to London. All of his specimens aboard Helen had been lost.

After a brief stay in England he embarked on a journey to the Malay Archipelago (now Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia). During this eight year period he collected more than 126,000 specimens, several thousand of which represented new species to science. While travelling, Wallace refined his thoughts about evolution and in 1858 he outlined his theory of natural selection in an article he sent to Charles Darwin. This was published in the same year along with Darwins own theory. Wallace eventually published an account of his travels The Malay Archipelago in 1869, and it became one of the most popular books of scientific exploration in the 19th century.

Upon his return to England, in 1862, Wallace became a staunch defender of Darwins landmark work On the Origin of Species (1859). He wrote responses to those critical of the theory of natural selection, including Remarks on the Rev. S. Haughtons Paper on the Bees Cell, And on the Origin of Species (1863) and Creation by Law (1867). The former of these was particularly pleasing to Darwin. Wallace also published important papers such as The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man Deduced from the Theory of Natural Selection (1864) and books, including the much cited Darwinism (1889).

Wallace made a huge contribution to the natural sciences and he will continue to be remembered as one of the key figures in the development of evolutionary theory.

Wallace died on 7th November 1913 at the age of 90. He is buried in a small cemetery at Broadstone, Dorset, England.

PREFACE

THE present volume consists mainly of a reprint of two volumes of essays Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection, which appeared in 1870, which a second edition in 1871, and has now been many years out of print; and, Tropical Nature and Other Essays, which appeared in 1878.

In preparing a new edition of these works to appear as a single volume I have thought it advisable to omit two essaysthat on The Malayan Papilionid as being too technical for general readers, and that on The Distribution of Animals as indicating Geographical Changes, which contains nothing that is not more fully treated in my other works. Another essayBy - Paths in the Domain of Biologyhas also been partly omitted, one portion of it forming a short chapter on The Antiquity and Origin of Man, while another portion has been incorporated in the chapter on The Colours of Animals and Sexual Selection. More than compensating for these omissions are two new chaptersThe Antiquity of Man in North America and The Debt of Science to Darwin.

Many corrections and some important additions have been made to the text, the chief of which are indicated in the table given below; and to facilitate reference the two original works have separate headings, and form Parts I. and II. of the present volume.

ALTERATIONS IN THE SECOND EDITION OF

CONTRIBUTIONS, ETC.

1ST ED. | 2D ED. | PRESENT VOLUME. |

| | Additional facts as to birds acquiring the song of other species | |

| 223A 223B | Mr. Spruce's remarks on young birds pairing with old | |

| 228A 228B | Pouchet's observations on a change in the nests of swallows | omitted |

| Passage omitted about nest of Golden Crested Warbler, which had been inserted on Rennie's authority, but has not been confirmed by any later observers. |

| | Daines Barrington, on importance of protection to the female bird | |

| Note A | |

372B | Note B | |

ADDITIONAL MATTER IN THE PRESENT VOLUME.

NATURAL SELECTION.

Additional facts by Leroy, Spalding, Lowne, and Dixon on the Nest-Building and other Instincts of Birds |

Dr. Abbott on Nesting of Baltimore Oriole |

Professor Jeitteles and Mr. Henry Reeks on Alterations in Mode of Nest-Building |

TROPICAL NATURE.

Note on Dr. Shufeldt's Investigations into the Affinities of Swifts and Humming-Birds |

THE ANTIQUITY OF MAN IN NORTH AMERICA.

THE DEBT OF SCIENCE TO DARWIN.

PARKSTONE, DORSET,

March 1891.

ESSAYS ON NATURAL SELECTION

I

ON THE LAW WHICH HAS REGULATED THE INTRODUCTION OF NEW SPECIES

Geographical Distribution dependent on Geologic Changes

EVERY naturalist who has directed his attention to the subject of the geographical distribution of animals and plants must have been interested in the singular facts which it presents. Many of these facts are quite different from what would have been anticipated, and have hitherto been considered as highly curious, but quite inexplicable. None of the explanations attempted from the time of Linnus are now considered at all satisfactory; none of them have given a cause sufficient to account for the facts known at the time, or comprehensive enough to include all the new facts which have since been, and are daily being, added. Of late years, however, a great light has been thrown upon the subject by geological investigations, which have shown that the present state of the earth and of the organisms now inhabiting it is but the last stage of a long and uninterrupted series of changes which it has undergone, and consequently, that to endeavour to explain and account for its present condition without any reference to those changes (as has frequently been done) must lead to very imperfect and erroneous conclusions.