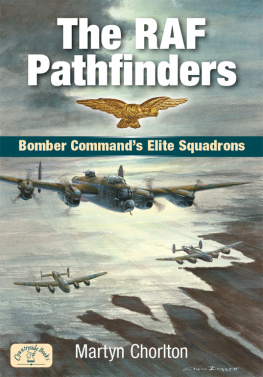

The RAF Pathfinders

Bomber Commands Elite Squadrons

Martyn Chorlton

Foreword by

The Revd Canon Michael Wadsworth

First published 2012

Martyn Chorlton 2012

All rights reserved. No reproduction permitted without the prior permission of the publisher:

COUNTRYSIDE BOOKS

3 Catherine Road

Newbury, Berkshire

To view our complete range of books,

please visit us at

www.countrysidebooks.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 84674 201 9

Cover picture showing Lancasters of 83 Squadron crossing the enemy coastline is from an original painting by Colin Doggett

Produced through MRM Associates Ltd., Reading Typeset by CJWT Solutions, St Helens Printed by Berforts Information Press, Oxford

Foreword

The River Ouse bisects pathfinder country. To the north of the river, acres of the ancient forestlands darken the road with shadow but suddenly through a gap in the trees the far horizon is glimpsed across the dead-flat peaty land that slopes down towards the south-west. Rain draining off the airfields could make the sleepy, almost motionless, Ouse into a torrent that overflooded its banks and filled the shady lanes with deep mud even in high summer. For there were many airfields, or, put another way, just one airfield, and over it the winged monsters slid, as once went the pterodactyls that are still found fossilized in the nearby chalk quarries.

From Len Deightons book, Bomber

T he Pathfinder Force of the RAF was an attempt to bring order and meaning and effectiveness into a situation where only a third of a bomber force on raids in the recent past had bombed within five miles of the target. These shortcomings were the subject of the Butt Report published in the second half of 1941. Although the C. in C. of Bomber Command, Arthur Harris, did not agree with a special force of lite aircrew to find targets and mark them, he was overruled by Portal and Churchill, and the maiden operation of PFF took place against Flensburg on the German-Danish border on 18 August 1942, seventy years ago.

Four squadrons formed the new PFF, and aircraft from these four squadrons went to war. There were Lancasters from 83 Squadron at Wyton, Stirlings from 7 Squadron at Oakington, Wellingtons from 156 Squadron at Warboys, and Halifaxes from 35 Squadron at Graveley.

Everyone of these Pathfinder squadrons (for that is what they became), was supplied by a different bomber group and, in January 1943, Pathfinders officially became 8 Group, with A/V/M Donald Bennett, the most efficient airman in the service, as Group Commander.

What follows now is an adapted excerpt from a sermon I preached on Sunday, 16 August, 1992, in a service to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the formation of the Pathfinder Force. As we are now celebrating the 70th Anniversary of the foundation and formation of the Pathfinder Force (19422012), we need to take a good long look at the bravery, motivation, and story of these men. Sadly, of course, the great majority of those original aircrew present in the congregation of 1922, are no longer with us.

Let us now praise famous men

And our fathers in their generations. (Ecclesiasticus 44:1)

Let us now praise famous men. We are here to praise your discipline, your courage and devotion, your high morale, and your decisive contribution to the peace we now enjoy, fragile though it is, fragile as peace always is. We are here to remember your Group Commander, A/V/M Bennett, who saw to it, after that first Pathfinderled raid on Flensburg, seventy years ago, that this fledgling force was given the equipment, the instruments to do the job, and saw to it too that only the best, the very best, came to Pathfinders from the main force squadrons; saw to it that courage and efficiency were the prime requirements for membership of the force, and not just the gratuitous accident of being known by the families of the great and the good.

What no one could ever know then, what is so hard to take in today, is that from Warboys airfield, where my father was, which has now, like Graveley, Bourn, Gransden Lodge, Downham Market, Little Staughton and others, gone under the plough (in appropriate prophetic tradition) from that airfield, of 93 seven-men Lancaster crews, posted to the squadron between June, 1943, and the time the squadron moved to Upwood in March/April 1944, only 17 survived. The rest took off into the dark, and fell from the night skies over Germany; a few aircrew, a very few aircrew from these missing aircraft, became prisoners of war. The majority perished. It was the same at other Pathfinder stations. After his experience at Oakington, where he was stationed with 7 Squadron, H. E. Bates captures the tears of things in an elegiac story called Theres no future in It, in which an anxious father tries to dissuade his only daughter, the apple of his eye, from marrying a Pathfinder aircrew member. Oakington lost three C.O.s in succession during the dark days of late 1943 and early 1944, while 97 Squadron at Bourn, on an appalling night in December 1943, lost one Lancaster over Berlin, and seven crashing in the fenland fog on their return (accounting for the lives of 49 men, while six were injured). That same night, Black Thursday it was called, Warboys lost another Lancaster, which crashed on the Ely to Sutton road, while Gransden Lodge lost one aircraft which came down in fog barely half a mile from this cathedral church. Its a great life, if you dont weaken, muttered one Australian navigator in the Sergeants Mess at Warboys after one such shaky do. The rest of what that Australian navigator said I cannot repeat in this cathedral church. Let us now praise famous men, And our fathers in their generations.

Twenty-five minutes it took to run the gauntlet of the Berlin defences from end to end at full stretch. And as you took off into all this, there was that little knot of WAAFs and well-wishers waving you off. For we must not forget the WAAFs and their contribution. It was hard for the WAAF who had to drive a crew out to their aircraft to realise and she did realise it that for many of them she was the last female, and the last person, they would see on earth.

Among that host of well-wishers waving off the aircraft would be not a few girlfriends and wives; even though wives were not allowed to live within five miles of an operational station, some were smuggled in to the host villages close by your aerodromes nonetheless. At Warboys, beyond the church and cemetery, a wire barrier blocked the ordinary road, as the runway ran across it. At that barrier many a girl stood waving her handkerchief, as her chevalier in bulky flying clothes waved to her from the astrodome on taking off.

A widow wrote that she saw her young husband off at Kings Cross Station on the 5 am to Huntingdon, and by 11 pm of the same day he was running into the flak barrage that blew him and his crew up over Berlin. And you ground crews, who literally kept the Pathfinder offensive on its feet, know all about those many unspoken goodbyes, as you saw your aircraft with your crew turn round on the hard standing to join other Lancasters on the perimeter track, as they taxied out to take off for the nights operations. And how you waited, you ground crew, over there near the flight huts for the overdue aircraft to come in, only turning away when it became obvious that the aircraft had not enough fuel to keep in the air.

In our remembering, and in the churchs remembering, I cannot help but see that figure, that young man, who set his face and his feet towards Jerusalem, and who knew what awaited him there. He knew what he had to do, and he knew he had to do it, as the words of the Creed run, for us men and for our salvation. In the background of my glimpse of this figure picking up his own cross and going on, I see too, on an occasion like todays, all those crews at the height of the bomber battle for Berlin, taking off in those appalling weather conditions in the winter of 1943/1944 to shatter the enemy and shorten the war, no matter what it cost in terms of their own lives.