George A. Reisch

M. Norton Wise

Angela N. Creager

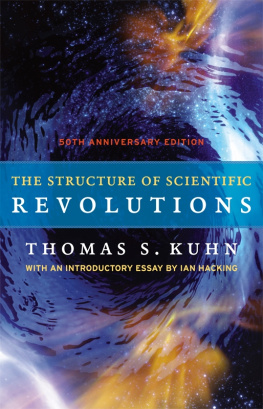

Like so many authors, Thomas Kuhn, then associate professor of the history of science at the University of California, Berkeley, had come to regret an earlier publishing commitment. When he had agreed some eight years previous in 1953 to contribute an article to the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science

This is the book that became The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,), must have been taken by surprise (and sometimes aback) by his celebrity.

Biographical Background

Not that Kuhn was a man of small academic ambition.thereafter, he plunged into war-related work on radar, which took him to France and then Germany at the end of the war. He returned to Harvard as a graduate student in physics in the fall semester of 1945, with John Hasbrouck Van Vleck as his thesis advisor. While there, he secured special permission to take philosophy (not history) courses, having been much impressed by an undergraduate encounter with the writings of Kant. Although he clearly was entertaining serious interests outside of physics, he completed his dissertation with dispatch and confessed later to dreaming of a Nobel Prize someday (surely his name was and is legion among physics graduate students).

But the course of his academic pursuits had begun to shift decisively, largely through the intervention of the then-president of Harvard, chemist James Bryant Conant. It was Conant who saw to it that Kuhn was awarded a junior fellowship in the Harvard Society of Fellows in 1948, and it was Conant who recruited Kuhn to teach in a new General Education course that taught nonscientifically inclined Harvard undergraduates about how scientists think through a series of historical case studies. Conant had been a prominent scientific administrator during World War II and believed that a scientifically literate citizenry was essential to the future of American democracy. Kuhn was assigned the task of preparing the case study in the history of mechanics from Aristotle to Galileo, a task that soon had him reading the historical work of the German medievalist Anneliese Maier and the Russian-French philosopher and historian Alexandre Koyr, figures to whom, along with French historian of chemistry Hlne Metzger, philosopher mile Meyerson, and American historian of ideas A. O. Lovejoy, he confessed his intellectual debt in the preface of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

In his own telling, however, it was reading Aristotle in the summer of 1947 that sparked Kuhns historical epiphany. With the sudden all-at-onceness that Kuhn later likened to a Gestalt switch, he realized that Aristotles account of motion was not simply wrong; it was about something else entirely. Aristotle, Kuhn realized, understood motion not just as displacement from point A to point B but as a special case of all kinds of change, from the maturing of organisms to the succession of the seasons. This habit of reading the past sympathetically, in its own terms and context, made Kuhn permanently wary of what he called (borrowing the phrase from the British political historian Herbert Butterfield) Whig history of science: narrating the history of science teleologically, as a triumphal conquest of error culminating in present scientific beliefs.to scientific advances without succumbing to the siren song of the conventional (among scientists as well as historians and philosophers) story of cumulative progress approaching ever nearer to eternal truths. He flirted with the analogy to Darwinian evolution, although it accorded ill with his scheme of periodic revolutions.

Although the germs of the ideas for Structure were planted in the context of Conants General Education course at Harvard (Kuhns The Copernican Revolution also began as one of the case studies), the manuscript took shape in California, where Kuhn quickly rose through the academic ranks at Berkeley after his joint appointment as assistant professor in the History and Philosophy Departments in 1956 and where he spent the academic year 195859 as a fellow at the Stanford Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. In the early 1960s, Kuhn undertook an oral history of quantum mechanics in collaboration with John Heilbron, Paul Foreman, and Lini Allen, resulting in Sources for the History of Quantum Physics (1967). Once Structure came out in 1962, Kuhn turned his attention to the history of quantum mechanics, a project that sent him to Copenhagen in 196263 (where he interviewed Niels Bohr), and eventually resulted in the book Kuhn himself considered his finest work, Black-Body Radiation and the Quantum Discontinuity, 18941912 (1978). By the time it was published, Kuhn was about to leave Princeton, where he had accepted an appointment in 1964, for MIT, where he spent the remainder of his academic career, from 1979 until his death in 1996. Structure had brought him international fame and innumerable honors, but he apparently considered it an essay, a preliminary attempt in need of expansion and improvement. His final, unfinished book manuscript was a philosophical and linguistic exploration of problems raised by the controversy over Structure