2014 Center for Contemporary Arab Studies. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

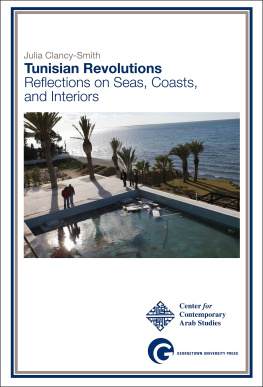

ON THE COVER: This image shows the looted villa of Mohamed Sakher al-Materi, Ben cAlis son-in-law, in Hammamet during January 2011 soon after the flight of the president and his entourage. Marco Salustro/Corbis

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases and special offers from Georgetown University Press.

A Note on Transliteration

Consistent transliteration for North African history poses a number of problems because there is no single agreed-upon system. Proper names, place names, and terms for institutions come from a range of languagesclassical Arabic, dialectal Arabic, Berber, and Ottoman Turkish. To complicate matters, proper names and place names often came into English through French, which frequently deformed the originals. Therefore, transliteration in this paper is the product of compromise. For the most part, a modified version of the transliteration system in the International Journal of Middle East Studies for Arabic is employed. However, only the ayn [c] and hamza [] are indicated. Turkish words, such as bey or dey, which refer to Ottoman political offices or titles, are used instead of the more accurate Arabic transliteration, bay. Arabic words have been given in their singular form, with -s added to the end for plurals. In cases where the plural form is in regular use in English, for examples, ulama or ashraf, the plural is employed.

Tunisian Revolutions

Reflections on Seas, Coasts, and Interiors

Julia Clancy-Smith

There has been no Arab Spring:

The perfume of its revolutions

Burns the eye like tear gas.

Tariq Ramadan, Egypt: Coup dtat, Act II, 2013

Introduction

The port de plaisance (yacht basin) in the city of Munastir abuts a promontory that still bears the skeletal outlines of a nineteenth-century Italian fabricca (fish-rendering factory); not far away are the remains of Punic, Roman, and Byzantineas well as medieval Islamic, Spanish, and Ottomanfortresses, businesses, and residences. Clearly, places such as this in the heartland of Africa Proconsularis, as the Roman Empire called its first African colony, have attracted other empires as well as commercial and pleasure interests for millennia. Looming over the promontory today is a five-star tourist complex. When I visited the port of Munastir, now a seaside resort, with a colleague from the University of Tunis in 2009, I noted with satisfaction that the customers for the well-appointed hotels, cafs, and bars were Tunisians as well as internationals. But it had not always been this way. Four decades ago (when I resided in Tunisia as a Peace Corps teacher), the countrys hotel clientele had been almost exclusively French; the locals labored as waiters, cooks, maids, and other staff members. Nevertheless, from the late 1970s on, the tourist industry offered women some of the countrys first professional management positions; and today, this sector is one of the University of Tuniss most popular majors for both women and men.

The extraordinary expansion of Tunisias middle classamong the largest in the Arab worldstarting in the late 1980s has put family meals and vacations in the countrys countless shoreline resorts within reach of many, but not all, of its citizens. Indeed, the emergence of this middle class was intimately tied to international tourism as well as to worker remittances, the countrys phosphate industry, and the relocation of light manufacturing from Europe to Tunisia. Needless to say, Tunisias tourist industry has deeply distinguished it from its Maghribi neighbors to the east and west. One can hardly imagine a vacation advertisement like the following one for Libya even before the 2011 war: Visitez Tarablis, pays de mer et de lumire (Visit Tripoli, country of sea and light).

However, Munastirs yacht basin also yielded other data. Most of the luxury vessels in port for winter appeared to be owned by transnationals, judging by their flags and names. Moreover, if one goes slightly inland, the olive groves (whose origins in the distant past can only be imagined) suggested another, quite sinister view of global investment capitalism cum travel industry. Grids of productive trees had been auctioned to the highest bidder and slated for destruction to make way for new villas built for the high-end transnational yachting class. But the 20089 global financial and economic crisis and subsequent political unrest severely depressed the tourist industry, which suffered a calamitous drop after the uprisings early in 2011.

As was also true for Carthage and Sidi Bou Sacid, Munastir had become a potent symbol of the Ben cAli regimes excesses even before the countrys Jasmine Revolution of 201011 because of the palatial compound there occupied by Mohamed Sakher al-Materi, the presidents son-in-law. Indeed, luxurious seaside palaces and real estate claimed by the extended Ben cAliTrabelsi clans were among the first political targets after Ben cAlis hasty departure in January 2011. Soon thereafter, the National Commission of Investigation into Corruption and Malfeasance (Commission nationale dinvestigation sur les affaires de corruption et de malversation) began its work, opening an initial five thousand dossiers into widespread, systemic graft centered upon Mediterranean real estate and the business of tourism.

This essay argues for a longue dure approach to Tunisias unfinished revolutions. As a small excerpt from a larger project in progress, it raises five seemingly disparate questions in search of a coherent framing narrative:

When and why did Tunisia become a Mediterranean playground for transnational elites, while its interior (the south, border, and central regions) suffered increasing neglect and marginalization?

Where and what is the interior, and how can environmental history deepen understandings of social movements, power, and divergent regionalizations?

How did women and gender configure two fundamental identities promoted by the newly independent Tunisian statesecular modernity, and a unique Mediterranean personality?