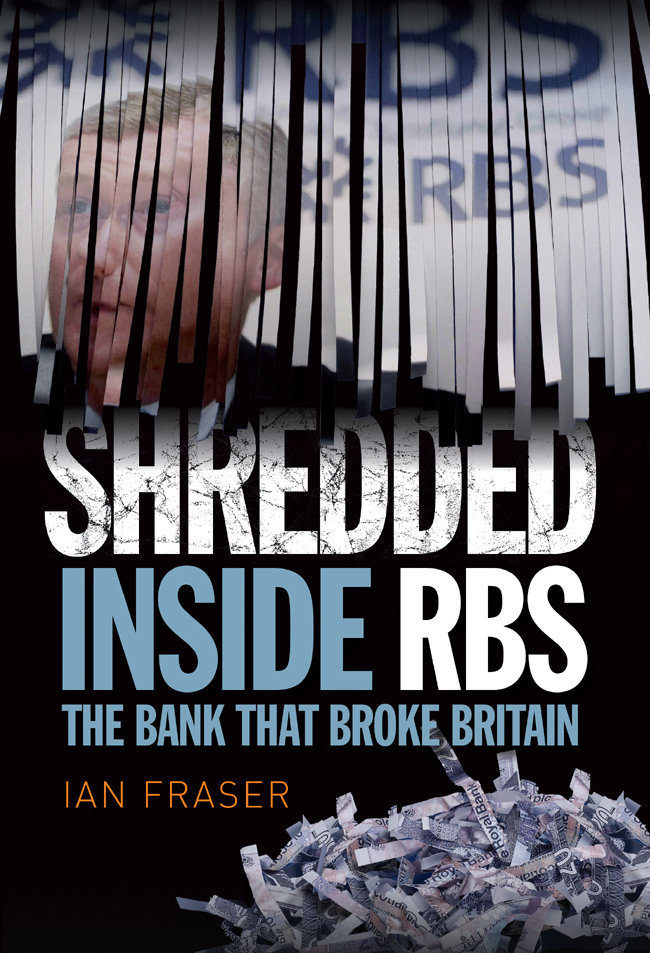

SHREDDED

This eBook edition published in 2014 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Ian Fraser 2014

The moral right of Ian Fraser to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 138 5

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 623 6

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

To Gail, Eleanor, John and Flora

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Shredded is the product of one-to-one interviews with about 120 current and former employees of the Royal Bank of Scotland and related companies. Most, but not all, had left the bank by the time I interviewed them. In the face of a system of corporate secrecy, underpinned by non-disclosure agreements and a fear of retribution, all but a handful preferred to remain anonymous. Many of the people I interviewed have been severely impoverished as a result of the banks collapse, given the number of shares they had accumulated over the years. Some have been psychologically scarred.

I am also grateful to numerous former senior advisors to the bank including investment bankers, accountants and consultants institutional investors in the bank, former chief executives of rival banks, senior politicians, regulators, financial journalists and corporate victims of the bank. In most cases, they too preferred to remain anonymous. I would like to offer special thanks to RBSs former chief executive and former chairman, Sir George Mathewson, who agreed to be interviewed on several occasions and provided me with all his speeches and a selection of related correspondence ranging from 1987 to 2006. Others who were willing to speak on the record for the purposes of this book included: Mathewsons former colleague Iain Robertson, who was with the bank from 1992 until March 2005 and was latterly non-executive chairman of its corporate banking and financial markets division; the former chairman of the management board of ABN AMRO, Rijkman Groenink; Killian Wawoe, a former human resources head at ABN; the former UK regulator and author of the March 2000 report A Review of Banking Services in the UK, Don Cruickshank; Simon Samuels, head of European banks research at Barclays; and the Edinburgh-based financier Peter de Vink.

In terms of direct assistance with the research and writing of this book, I am indebted to Jamie Mann and Frances Coppola who helped me to write specific chapters, as well as to Professor Stewart Hamilton, Richard Smith, Mike Parker, Colin Donald, Michael Campbell, Michael Moss and Nick Kochan who reviewed various chapters, provided moral support and made some valuable suggestions for improvement. Other writers and journalists who have provided insights and assistance include Shanny Basar, Chris Baur, Iain Dey, Simon English, Sean Farrell, Daniel Gross, Marc Hochstein, Patrick Hosking, Bill Jamieson, Kenny Kemp, Peter Thal Larsen, Joris Luyendijk, Richard C. Morais, Ray Perman, Nils Pratley, David Rothnie, Jeroen Smit, Yves Smith, David Torrance, Steven Vass, Siddharth Verma, Harry Wilson, William Wright and Alf Young. The team at Birlinn Hugh Andrew, Andrew Simmons and Tom Johnstone have been incredibly supportive throughout and Patricia Marshall has been meticulous in her copy-editing. Finally, Id like to thank my daughter Eleanor for her sterling work transcribing some of the interviews.

All unattributed quotes come from people, including ex-Royal Bank of Scotland insiders, who wished to remain anonymous.

Any errors are, of course, my own.

Introduction

When I was reporting on the Royal Bank of Scotland for newspapers including the Sunday Herald and The Sunday Times from 1999 to 2008, I always felt there was something not quite right about the place. It was a company that didnt actually make anything but which had a manufacturing division. It trumpeted its environmental credentials, yet funded some environmentally disastrous activities. It presented its Private Finance Initiative projects as socially responsible, even though most were a rip-off for taxpayers. It employed at least 70 in-house media relations staff, yet rarely told journalists anything. It had a dignity at work policy, yet treated many of its staff abysmally. It claimed that its marketing was responsible, but sent a pre-approved 10,000 credit card to a dog named Monty. It claimed to treat customers who were having trouble repaying their debts fairly and responsibly, but it hounded some of them to within an inch of their lives. Its CEO Fred Goodwin was lionised in the media and by analysts and showered with awards, although he was a sociopathic bully whose achievements had been massively over-hyped.

Most striking of all was RBSs market value. At times, this seemed to be detached from reality. On the way up, the bank used to boast that, by market capitalisation, it was worth more than Coca-Cola and more than Sony and Apple combined. In April 2007, its market value reached 64 billion more than all the other listed companies in Scotland put together and about 4.6 per cent of the FTSE-100. Its persistent triumphalism and the greed of its top brass grated with me. And yet, as a Scot living mainly in Edinburgh, part of me was proud to have a seemingly successful global giant on my doorstep. So many other Scottish firms had succumbed to takeover. At least here was one that was bucking the trend, acquiring overseas firms, building a global brand and creating jobs locally.

But RBS is a case study in how not to manage and regulate a bank. Soon after Fred Goodwin became the chief executive on 6 March 2000, things started to go seriously awry. And the most serious problem

There were some shocking governance failures, including that the board was so in awe of Goodwin they let him run the bank as a personal fiefdom, but with some dangerous cult-like characteristics (at least until their somewhat half-hearted attempt to rein him in in June 2005). Institutional shareholders also have a lot to answer for. Having backed Fred Goodwin in the NatWest takeover battle, they egged him on over the next two or three years and 94.5 per cent of them voted in favour of the disastrous ABN AMRO takeover. And, where regulation and banking supervision are concerned, the RBS saga is extraordinary. Why, for example, did the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown allow the bank to grow to a scale that far exceeded anyones ability to manage it? Why was the bank allowed to leverage itself 70 times, putting itself and the wider UK economy at risk? Why did the Blair and Brown governments invariably side with the bank in its disputes with the regulator, hobbling the FSAs ability to regulate it? Why has nobody been properly held to account for its collapse? I try to answer these questions in the book.

A lot of people are astonished that no one has been prosecuted for destroying RBS. And there is the view that, if the UK state had been so minded, it could readily have prosecuted a number of RBS executives for alleged crimes including fraud, conspiracy to defraud, fraudulent trading, false accounting and regulatory offences under the Companies Act 2006.

Unfortunately, however, prosecuting high-level financial crimes is notoriously difficult, especially if hard evidence like emails and secret recordings are not available. Another reason is that, unlike countries like Iceland and Nigeria, the UK doesnt have much appetite for the prosecution of mainstream bankers. So what we have had instead is diversionary tactics, faux outrage and political bluster.