This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Katsaros, Laure.

New YorkParis : Whitman, Baudelaire, and the hybrid city / Laure Katsaros.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-472-11849-6 (cloth : acid-free paper) ISBN 978-0-472-02870-2 (e-book)

1. Whitman, Walt, 18191892Criticism and interpretation. 2. Baudelaire, Charles, 18211867Criticism and interpretation. 3. New York (N.Y.)In literature. 4. Paris (France)In literature. 5. Comparative literatureAmerican and French. 6. Comparative literatureFrench and American. I. Title.

PS3233.K38 2012

811'.3dc23 2012019744

Introduction

To write one hundred of these belabored nothings, I have to be in a constant state of elationand I also need the strange intoxication of spectacles, crowds, music, even streetlights!

Charles Baudelaire, letter to Sainte-Beuve, May 4, 1865

New-York loves crowdsand I do, too. I can no more get along without houses, civilization, aggregations of humanity, meetings, hotels, theatres, than I can get along without food.

Walt Whitman, New York Tribune, August 1881

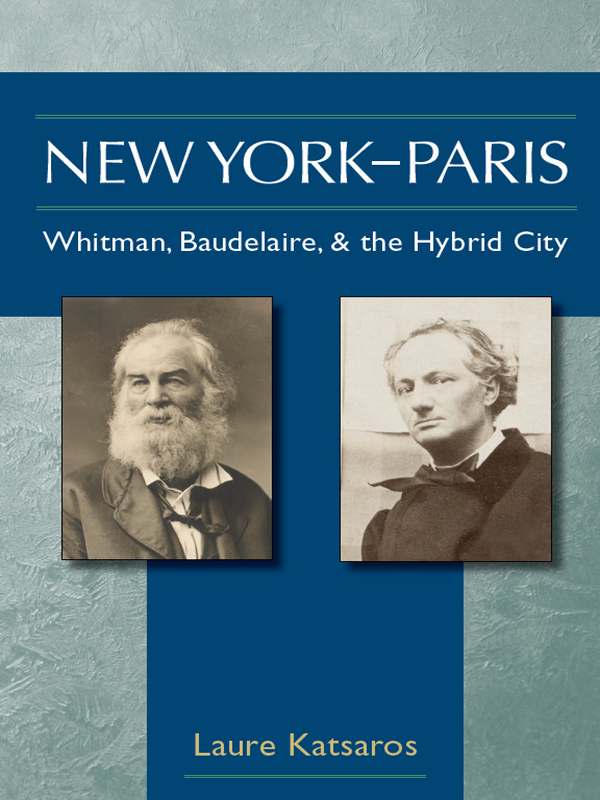

IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY STEREOSCOPES, two nearly identical images are printed side by side on a strip. If you look at them intently, a third, three-dimensional image emerges. But what happens when New York and Paris, Whitman and Baudelaire, are placed side by side? These two celebrated faces of the modern city seem to have almost nothing in common. In 1983, the Baudelaire scholar W. T. Bandy remarked that trying to find points of resemblance between Walt Whitman and Charles Baudelaire reminded him of a riddle about the American presidency: Why are Calvin Coolidge and Ulysses S. Grant alike? Both had thick black beardsexcept Calvin Coolidge.Mona Lisa. It has been almost impossible, ever since the middle of the nineteenth century, to see Whitman and Baudelaire in the same frame.

Though their life spans overlapped, their paths never crossed. Except for a brief period in New Orleans, Whitman lived in Brooklyn and New York (as Manhattan was then called) until the Civil War. Baudelaire never visited America, and left Paris only under duress. They did not translate each other's work, did not enter into a correspondence, and had no common friends. They showed almost no sign of being aware of the other's existence. Baudelaire, who made celebrated translations of Longfellow and Poe, knew English well, but no reference to Whitman can be found in anything he wrote. Whitman, who read French writers in English translation only, alludes to Baudelaire just once. In an essay entitled Poetry of the Future, Whitman refers to Baudelaire's article The Pagan School, which speaks of the corrosive consequences of an excessive love of beauty. The immoderate taste for beauty and art, says Charles Baudelaire, in the quotation by Whitman, leads men into monstrous excesses. In minds imbued with a frantic greed for the beautiful, all the balances of justice and truth disappear. There is a lust, a disease of the art faculties, which eats up the moral like a cancer. Adducing this argument as evidence that the hypertrophy of the aesthetic sense will inevitably erode the moral faculties, Whitman uses Baudelaire to justify his own belief that poetry must sing of real life and ordinary days, and not the hyperbolically poetic subjects that it had always been accustomed to invoking. The fact that Whitman saw Charles Baudelaire as the proponent of morality, moderation, and restraint reveals a profound misunderstanding of his contemporary.

The first edition of Leaves of Grass appeared in 1855, and until Whitman's death, was endlessly revised. Shortly after its first appearance, an anonymous English critic, alleging that Whitman's long lines had drifted from the regular rhythms of verse into the slack shapelessness of prose, claimed that Whitman was as unacquainted with poetry as a hog with mathematics.when he crossed over the boundary into the starkest prose. While Whitman exhibited a shocking lack of self-awareness, Baudelaire appeared pathologically self-conscious. One too primitive, the other too decadent, they seemed to come from opposite ends of time.

In 1926, T. S. Eliot wondered whether any age other than the nineteenth century could have produced more heterogeneous figures than Whitman and Baudelaire, explaining that, for Whitman, there was no chasm between the real and the ideal, such as opened before the horrified eyes of Baudelaire. Baudelaire saw the world caught in a hopeless struggle between an all-pervasive squalor and rare sparks of grace, whereas Whitman has been considered not only as the representative of a stereotypically American optimism, but also as someone who could find beauty even in the lowest and most common of spectacles. Baudelaire's irony creates an extraordinary distance between what he says and what he appears to mean. In contrast, it is easy to believe that a transparently candid Whitman exposes every aspect of himself in Leaves of Grass. Whitman seems to invite us to take him at his word; Baudelaire urges us to never trust what he says, or what he seems to have said, if only we could have pinned down his meaning.

The aesthetic differences between Whitman and Baudelaire are often seen as the offshoot of their opposing political views. On the rare occasions when they are compared, we inevitably find them at extreme and opposite ends of the political spectrum. It was as if the decline of one were indissolubly linked to the rise of the otherthe New World and the Old constantly at war with one another. From Baudelaire's perspective, America's gain would inevitably be France's loss.

Whitman, however, looked on France in a completely different light than Baudelaire looked on America. Although he grew up in Brooklyn, Whitman went so far as to claim the status of a real Parisian in a poem with a French title, Salut au Monde. Yet all that Whitman found most luminous about France was precisely what Baudelaire most abhorred. As Roger Asselineau has shown, Whitman pictured France as the capital of democracy in Old Europe and admired the revolutionary spirit of 1789 and 1848. In the eyes of Baudelaire, a writer like Sand, who extolled the virtues of the disenfranchised, wrote sentimental prose about the poor, and defended the rights of women, was a symptom of the irreversible decline of French culture. But the woman that Baudelaire likened to a latrine represented a political and literary ideal for Whitman.

In one of Baudelaire's prose poems, an abominably ugly man looks at himself in the mirror. When asked why he has chosen to inflict such a spectacle on himself, the man answers that in the name of the immortal principles of 1789 (namely, that all men are equal before the eyes of the law), no one can deny him the right to look at his own image. For Baudelaire, the egalitarian ideals of postrevolutionary France had a catastrophic effect on aesthetic values, and the poem is a thinly veiled allegory of the modern era. As usefulness became a more precious treasure than beauty, the inevitable consequence was that the public, instead of being horrified by ugliness, turned a blind eye to it. From Baudelaire's perspective, nineteenth-century France saw the collapse of the social and cultural system that had allowed the creation of art. But all of Whitman's poetry gives voice to the opposite belief. Every form of life, no matter how low, base, or degraded, is considered sacred in

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper