Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Casey Ruble and Fritz Engstrom in providing some of our case examples. Casey Ruble is a writer who has been helping mental health professionals for over a decade getting their ideas into print. Fritz Engstrom, MD, practices general psychiatry in Brattleboro, Vermont, where he is Medical Director at the Brattle-boro Retreat, a not-for-profit psychiatric and addictions treatment center. He teaches at symposia across the country and is author of Movie Clips for Creative Mental Health Education.

In addition, we would like to thank Gabriela Noyes for providing much of the material on pathological lying. Gabriela is a forensic psychology student working toward her PsyD at Alliant University of San Diego.

Chapter 1

Defining Deception

In the summer of 1998, Matthew Cecchi, a 9-year old boy, was at a beach near San Diego with his grandmother enjoying a sunny day when he asked his grandmother to accompany him to the restroom. As the grandmother stood outside waiting for her grandson, a disheveled young man emerged from the restroom. When Matthew did not, she became concerned and entered the restroom, where she found Matthew dead on the floor in a pool of blood. His throat had been slit from ear to ear, but he had not been physically or sexually assaulted in any other way. It was as if his attacker had just silently slipped up behind him, cut his throat, and then slipped away. Soon thereafter, Brandon Wilson, a drifter from the Northwest, was apprehended and charged with the murder. Upon being questioned, Wilson freely admitted to the killing but told police interviewers that because God told me to kill the child, he would be forgiven by Jesus. Wilson pled not guilty by reason of insanity, but the jury, unsurprisingly, convicted him of the murder. (Most juries find child murderers sane, notwithstanding the validity or lack of validity of mental health problems.) More interesting from our perspective is the problem this case raises in terms of simply defining deception. Was Wilson truthfully reporting that he heard the voice of God commanding him to kill this child? Or was he playing with his interviewers, trying to pass himself off as being mentally ill in order to mitigate punishment or perhaps receive attention and care from jail staff? Complicating the issue even further was the fact that many people who are not mentally ill (but rather, simply religious) claim to regularly hear the voice of God! The difficulty in addressing these questions points to just how hard parsing truth from fiction can be, as well as to the complexity of defining deception itself.

What Is Deception?

Lying. Deception. Truth. Truthfulness. Falsehood. The definitions of these terms and others like them overlap and are poorly understood.

The term false has at least two meanings. The broader meaning refers to facts that are wrong, incorrect, or not true. A person who claims that cats have three legs, for example, is asserting a falsehood. The analysis of false facts comes from either science or epistemology.

The narrower meaning of false refers to whether there is an absence or presence of the intent to deceive. If someone says a cat has three legs when she knows it has four, this is considered a false statement. This analysis comes not from science or epistemology but from moral psychology.

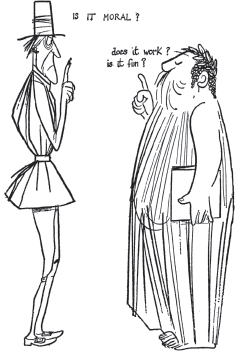

Whereas the analysis of the truth or falsity of a fact is impersonal, the analysis of intent is personal. In other words, determining that a fact is false requires no moral judgment. But determining that a person is false does invite a moral analysis. Throughout history, the majority opinion toward such false persons has been that they are bad, or at least that the action of lying is bad. For example, Jesus called Satan the Father of the lie (John 8:44); 2000 years later, Gandhi noted: My research gave me the revealing maxim that Truth is God,' instead of the old God is Truth' (Harijan 9-8-42). This contrasts with a minority opinion that lying is good! In Will To Power (1885) Friedrich Nietzsche wrote: A great man: What is he? He rather lies.

Whether lying is good or bad (or at least acceptable or not), some sources claim that a lie (or the absence of truth) is easily recognized. The Quran (2:256) notes: Truth stands out clearly from evil. But problems in defining the truth have been noted since the time of Jesus, when Pontius Pilate famously asked: What is truth? (John 2:248). One reason for the ongoing confusion is that, like false, the term truth can be used in at least two different ways. The broader meaning applies to statements of fact: Is the assertion factually correct (making it true), or is it factually incorrect (making it false)? The methodology to prove the factual truth of a statement is (in modern times) based on the methods of science. The analysis of what it means for facts to be true is based on the analytic methods of epistemology. Both of these inquiries are blind to the motive or the intent of the person making the assertion.

In contrast, the narrower meaning of truth, based on the methods of ethics, pertains to whether the person making the statement wishes to convince another person that the statement is indeed true, regardless of whether it actually is. For example, if someone honestly believes that a cat has three legs and is trying to convince you of the veracity of that assertion, she would still be considered truthful despite the fact that the statement she's making is false. If she does intend to deceive, however, one may conclude that she is a false or untruthful person.

But things can get tricky if there is evidence of noble motivation for the deception. For example, if parents considering divorce tell their young child, Don't worry, honey, everything is okay, in an effort to spare the child the anxiety of anticipating a separation that may never come to pass, should they be considered false or untruthful?

Changing Concepts of Deception

Our understanding of deception has changed over the past 200 years. Rooted in a Victorian sense of morality, the old view was that deception is an issue of ethics, and that the relevant distinction is between those who practice virtue (the truth-tellers) and those who practice vice (the deceivers).

The more modern view holds that deception is better conceptualized as an issue of evolutionary biology or psychology, and that the relevant distinction is between those who are better evolved to survive (the efficient deceivers) and those who are less likely to survive (the less efficient deceivers). All living organisms (including plants and the most primitive animals) have developed techniques to help them survive, many of which involve deception. Think of the moth whose markings make it look like tree bark, or the mother bird that feigns a broken wing to lure a predator away from her nest. The distinction, therefore, is not between those who deceive and those who don't, but rather between those who deceive efficiently and those who do not.

Deception and Mental Health: Diagnoses

Over the past few centuries, there has been a tendency to medicalize social and moral problems. Rightly or wrongly, addictions were originally considered sins; they then became moral problems; now they are considered medical diseases recognized by both the

Next page